The Rich, Deeply Personal History Of The Cornrow

And their role in African American resistance.

My mom, half English and half Ghanaian, grew up in West Africa and learned how to braid cornrows in childhood. She would braid my hair ever since I had enough strands on my head, and still offers to do so today. Sometimes I accept, eager to feel like a child. Other times I feel too stubborn, eager to present as an adult. I tell myself it's time to learn how to braid my own hair. Cornrows are so deeply personal to my mother and where she grew up and, in turn, deeply personal to me. That's the beautiful thing about the African hair braiding tradition—it continues being passed down, generation by generation. It's an identity and a little piece of wearable history.

Hair braiding is deeply personal to Black culture; certain styles, like cornrows, carry centuries of history. Eager to learn more about the hairstyle that's engrained in my childhood, I spoke with Lori L. Tharps, a journalist, educator, speaker, and co-author of Hair Story: Untangling The Roots Of Black Hair In America, to uncover the rich and complicated history of cornrows, from slavery and resistance to schools and the courtroom.

The Origins Of Resistance

D H/ZUMA Press Wire/Shutterstock

D H/ZUMA Press Wire/ShutterstockThe term "cornrow" originated in the diaspora to reflect the slaves' circumstances—the same style was called "cane row" in the Caribbean. Cornrows offer a beauty aspect, but also a practicality aspect and an identity aspect. "We know of all of the very elaborate hairstyles that African people styled their hair in pre-colonial or pre-slaved or pre-diasporic movements—[they] took days to create, maintained with special tools and products," Tharps says. But when African people were brought to the Americas and the Caribbean as slaves, they obviously didn't have the time or products or resources to do these styles. Instead, cornrows could be done relatively easily without a lot of extra work. The style, characterized by the way the braid hugs the skull, was considered easy to achieve, with no tools or products necessary, and could last for over a week.

While cornrows could and can be very simple, they can also be very elaborate. "There are suggestions that cornrows were used to send messages between different Black people and that they were used to make maps for escape," Tharps says. Historically, in Africa, different hairstyles meant different things and were often used to send messages. "There is actual documentation that the enslaved people in Brazil did use cornrows for maps to escape," she says. Beyond sending messages, cornrows also played a crucial role in resistance during slavery. Seeds would also be braided into cornrows so that enslaved Africans could plant their own gardens and grow their own food—this was a symbol of hope and prosperity.

Now, they're a common protective hairstyle that Black people turn to to give their hair a break from combing, tugging, styling, and the inevitable breakage that comes along with having delicate kinky or coily hair.

The Cultural Appropriation

Shutterstock

ShutterstockDuring slavery, Black people who wore cornrows often covered them with scarves; the style wasn’t considered “public hair.” That idea, that cornrows were somehow inappropriate or unpresentable, carried into modern times. Black people were told the style was unattractive and unprofessional, particularly in the workplace, while white people who adopted cornrows were celebrated. “Bo Derek wore cornrows in the ’70s—it was really an intentional publicity stunt by her husband, who was also her manager,” Tharps says. “He knew that braiding her hair in cornrows would draw attention, because she didn’t even have a big career at that point. People were calling them ‘Bo Braids.’”

Still, Black publications and icons worked to reclaim and legitimize the style. In 1972, Essence, a magazine always known as a safe space for Black women that sought to make us feel seen, featured cornrows on its cover. A year later, Cicely Tyson appeared on the cover of Jet wearing cornrows. Decades on, Beyoncé requested to wear cornrows for Vogue’s cover in 2018, a first in the magazine’s history, while Teen Vogue featured Serena Williams rocking the style. Black celebrities also began wearing cornrows more frequently on red carpets—often without the same praise afforded to their white counterparts, but present nonetheless. Tyson wore cornrows throughout the ’60s and ’70s, and Alicia Keys has remained a devoted cornrow girl, from the 2003 Met Gala to the 2020 Grammys and beyond. These moments affirm that cornrows deserve visibility—that they aren’t meant to be hidden at home, and that their place is everywhere and always, even on the most visible stages.

But as with all things made by and for Black and Brown people, the cornrow was soon appropriated, and the appropriators were applauded. Cornrows were dubbed a "trend" when Kim Kardashian, known for seeking proximity to Blackness, started wearing them. "There was this attribution to her, as opposed to the actual African origins," Tharps says. "We live in such a multicultural society and people are sharing and borrowing different cultural touch-points. But Black women were literally sent home from work for wearing cornrows."

Appropriation becomes appropriation due to a lack of education and the feeling that someone is "trying on" your culture for fun. Would non-Black people wear these styles if they knew and understood the cultural significance, dating back to slavery?

Taking It To Court

SplashNews.com/Shutterstock

SplashNews.com/ShutterstockUp until as recently as 2018, men, women, and children were often sent home from work and school for wearing cornrows, as well as other natural or protective hairstyles, because they were "distracting" or "unprofessional. This still happens to this day, but we luckily have legislation in place now that makes it far less common. The CROWN (Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair) Act, created in 2019 and passed in 2022, prohibits discrimination based on hair texture, as well as protective styles like locs, twists, and braids (cornrows included, of course). "[We want to get to a place] where Black people wear the hairstyle and it's not demonized or against the law or preventing them from being able to work and make a living," Tharps says. "That's where the problem is and where the disparity is and what makes it unfair or a burden on Black people, who originated the style in the first place."

Present & Future

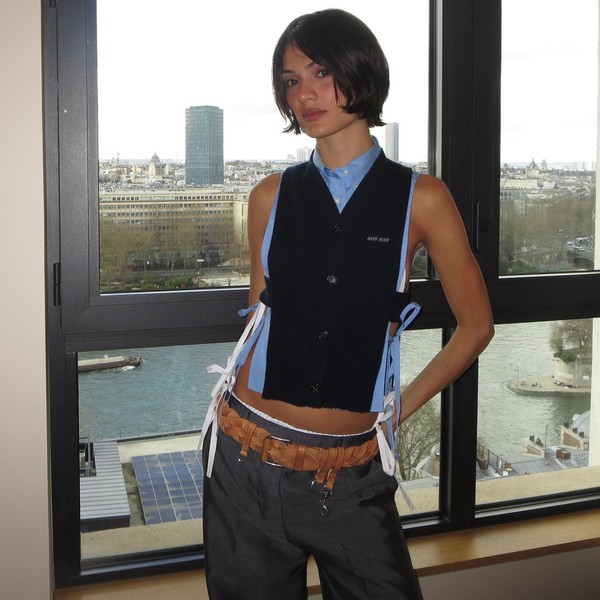

Matt Baron/Shutterstock

Matt Baron/ShutterstockWhile the CROWN Act has been enacted in 27 states and Washington, D.C., there are still 23 states that have yet to sign. The collective mindset around Black hairstyles is difficult to change. The answer, perhaps, is continued representation: the more influential celebrities and public figures, like Zendaya and Yara Shahidi, proudly wear their cornrows, the more normalized they become. But still, wearing cornrows is seen as a radical power move, or a bold choice. Until that changes, there's still so much work to be done. "That's how change happens," Tharps says. "It never changes all at once. It happens gradually."