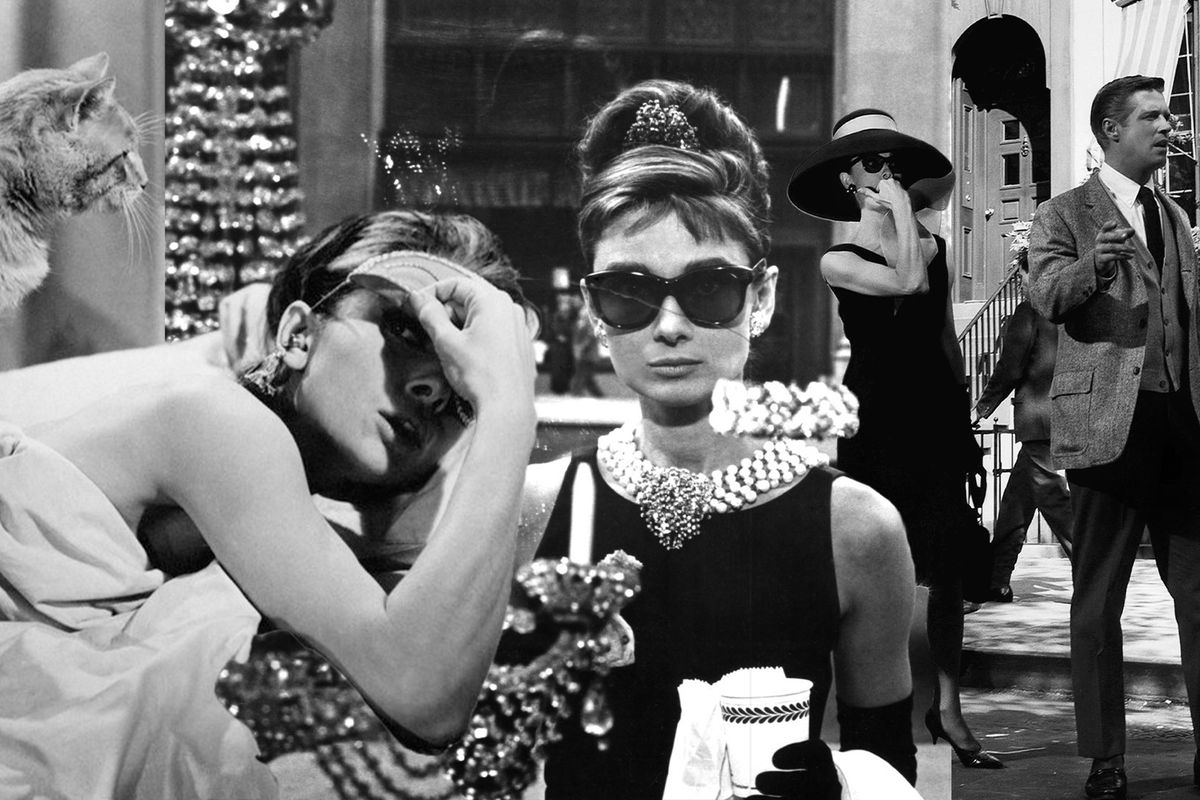

Breakfast At Tiffany's, Attachment Theory, & A Cat Named Cat

Our favorite Manhattan socialite with an avoidant attachment style.

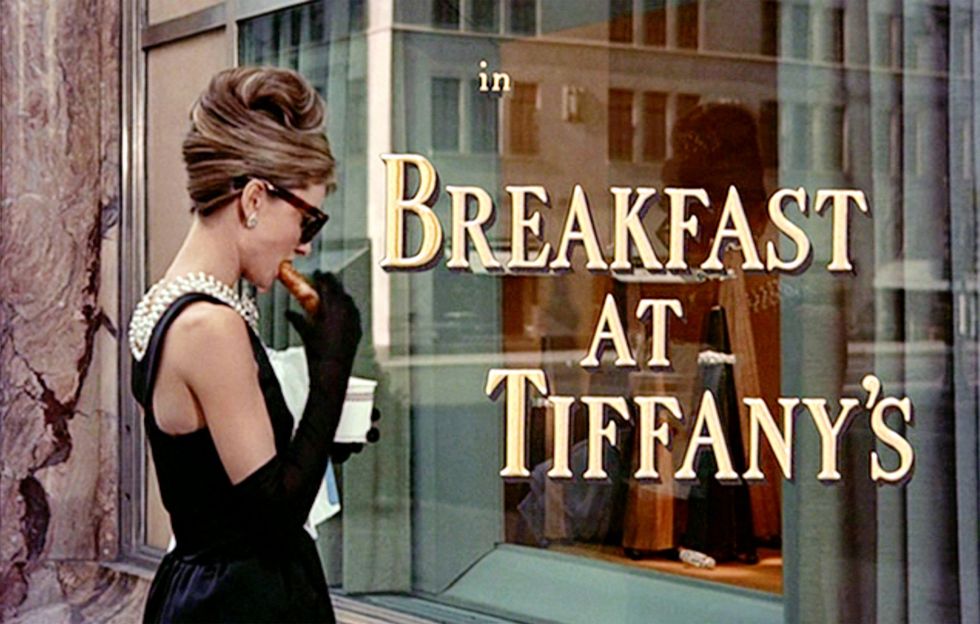

From the moment we meet Holly Golightly (portrayed by the most elegant woman to ever walk the earth, Audrey Hepburn), an inherently lonely energy follows her out of a yellow taxi, onto an Upper East Side sidewalk, and in front of a window displaying some of New York City's most coveted items. The sun is just rising and the Manhattan street is empty which, in a city of eight million people and borough of almost two million, can feel eerily off-putting. She pulls out a croissant, already has a coffee in-hand, and enjoys "Breakfast At Tiffany's" as an instrumental version of "Moon River" plays. This scene is set up to introduce us to our main character and these are the things to note: she is alone, she enjoys the finer things in life and, as the music suggests, we are meant to sympathize with her.

In the following scene, she arrives home to a suitor waiting for her. We learn that they've been on a few dates, that he wined and dined her which he is now choosing to use against her, and she is now, for lack of a better word, ready to discard him. We quickly learn that her loneliness is partially by her own doing, but by the end of the film come to an understanding that this isn't entirely her fault: our approach to relationships is laid out by those who came before us.

CBS/Getty Images

Indulging in an artisanal pizza in Brooklyn in a similar but less moody manner as Holly with her croissant in Manhattan, I rewatched "Breakfast At Tiffany's" and couldn't help but think about attachment theory, something I am personally so interested in, along with the general idea that our parents (and other adults close to us while growing up) really (have the power to) screw us up.

"Attachment theory helps us understand how our earliest relationships with parents or primary caretakers shape the way we relate, connect, and feel either secure or insecure with others. When we’re young, we learn about love and safety not through ideas, but through our lived experiences," marriage and family therapist, and author of "The Origins Of You," Vienna Pharaon said. "At its core, attachment theory is really the study of our origin wounds—the early relational experiences that shaped our expectations of love, our capacity for trust, and the strategies we use to protect ourselves from getting hurt again."

CBS/Getty Images

Holly is woken up by her cat (named Cat) while wearing a Tiffany blue sleep mask with metallic gold trim and tasseled earplugs. When Paul Varjak, her new neighbor and soon to be love interest, he enters her minimally furnished and decorated apartment and assumes that she, like him, just moved in. Golightly has lived in that apartment for about a year and her home is a direct reflection of her inability to commit, discomfort around the idea of permanence, and unfamiliarity with security—because she never had it. She even doesn't feel the right to give her cat a proper name, as he doesn't belong to her and she doesn't belong to him. We learn that Holly's parents passed away when she was ten years old leaving her in foster care. She ultimately ended up running away and being taken in by a seemingly nice and normal veterinarian, Doc Golightly, who ended up not being nice or normal at all—he took advantage of her and married her when she was just fourteen years old. In the film, the sexual abuse and predatory relationship is somewhat brushed over, used simply as exposition to support Holly's need to be independent.

"Holly presents with a deeply avoidant attachment style, shaped by profound childhood abandonment and early experiences in which adults were unsafe, unreliable, or overtly exploiting her," Pharaon says. "Her history with Doc Golightly hints at a childhood marked by instability and a premature need to care for herself. Whether or not viewers register it consciously, Holly was a vulnerable adolescent girl taken in by an adult man who then married her—an experience that collapses caregiving, survival, sexuality, and dependence into one confused relationship. That dynamic alone wires a child’s nervous system to associate closeness with danger, obligation, and loss of power."

Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

Silver Screen Collection/Getty ImagesIt's so easy to characterize Golightly as a woman who uses and discards men when you don't have the proper tools to dissect her behavior. It's easy, especially as a young girl watching and falling in love with the film as I did when I was a pre-teen, to chalk her defensive mechanisms up as fun quirks, elegant charm, and a spunky, carefree attitude. But, at the end of the day, our pasts do unfortunately define our futures in some way. It is up to us (to an extent) how much we let our trauma present itself in present day relationships and dynamics and how much work we put in to unpack that. Holly copes with her trauma by constantly reinventing herself, from country girl to Manhattan socialite, for example. She believes that if no one truly knows who she is, no one can hurt her. When people (anyone, but especially men in the film) get close to her, her guard goes up—she pushes them away or vanishes herself. She views relationships as purely transactional, her ideas of closeness and love having been completely destroyed by her predator and the grief of losing her parents at such a young age.

"She functions through performance, charm, and relational distraction, never anchoring in one identity long enough to be truly known. Her pattern of taking money or favors from people serve two psychological functions: it keeps relationships safely transactional so she never has to risk emotional dependence, and it gives her a sense of control she lacked as a child," Pharaon says. "I see her avoidance as self protective, rooted in a childhood where closeness was dangerous, adults were not safe, and survival required constant reinvention. Holly learned that she could rely only on herself. As an adult, she keeps intimacy at a distance, turns relationships into roles, and uses charm and mobility to keep emotional reality from catching up with her."

CBS/Getty Images

Paul, her neighbor turned lover, sees her for who she is and doesn't assume ownership over her, so Holly is comfortable giving into a platonic, non-transactional relationship. Even so, as Paul shows more and more interest in her inner world, Holly shuts down and declares "I hate snoops"—vulnerability feels completely and utterly unsafe to her. It's not that Holly doesn't want a romantic relationship, she just doesn't know that she deserves one and doesn't think it's possible. Although these ideologies came from childhood, she never took the time to address them and so they inevitably show up in her adult life and relationships. "Childhood trauma doesn’t just disrupt your sense of safety in the moment, it shapes the entire relational blueprint you carry into adulthood," Dr. Pharaon says. "Origin wounds leave us questioning our worth and value, our sense of belonging, how prioritized we feel, how much we trust those around us, and whether or not we feel safe."

Holly momentarily abandons the pure relationship she is developing with Paul for another transactional relationship, that situation blows up, she turns to Paul, and when she is feeling too vulnerable and exposed for comfort, once again pushes him away. Not only that, but she also abandons her cat named Cat, a final representation of her fears when it comes to emotional bonds and becoming attached to any and all living things. She says, referring to her and Cat, "We belong to nobody and nobody belongs to use, we don't even belong to each other." With that, she opens the door of the yellow cab and sets Cat free.

Confronting attachment issues often comes with putting yourself out there in the most terrifying way possible, against everything that you brain and body are telling you is safe. "Breakfast At Tiffany's" culminates with Holly running through the rain towards both Cat and Paul, a final admission of her desire for love, affection, and closeness. It feels like the ultimate act of bravery but, despite a romantic kiss in the New York City rain, doesn't feel like a perfectly happy ending—although she is giving into her feelings now, we don't necessarily know how these relationships (with Paul and with Cat) will ultimately play out. The lack of full closure lends to the relatability of the conclusion—they rarely occur perfectly. Holly Golightly, who I used to view as the epitome of a chic and glamorous woman, felt completely retable in that moment and I am personally glad that she, even just for this emotionally heightened rainy moment, put herself out there.