A No-B.S. Guide to Sunscreen Safety

The ins, outs, and WTFs of physical versus chemical sunscreen ingredients.

Of all of life’s great ironies—traffic jams when you’re already late, “No Smoking” signs on your cigarette break, et cetera—perhaps the greatest is this: Sunlight is essential to humankind’s very existence, and yet consumers spend nearly $400 million a year shielding themselves from it. Yes, I’m talking about sunscreen, and no, it’s not a simple subject to cover.

Perhaps you’ve realized this. Perhaps that’s why you’re here. What was once a pretty straightforward practice—apply sunscreen, and apply it often—suddenly seems complicated. Why? Well, for starters, the state of Hawaii, the city of Key West, and the US Virgin Islands all recently passed legislation banning the sale of certain sunscreen ingredients thought to damage coral reefs. A paper published in medical journal Reproductive Toxicology links the use of one common SPF ingredient to a birth defect called Hirschsprung’s disease. In the past year alone, the Food and Drug Administration released two studies showing that six chemical sunscreens absorb all the way into the bloodstream after topical application; the long-term health implications of this are still unknown. Really, it’s no wonder you’re starting to wonder WTF is in your SPF.

According to dermatologists, environmental toxicologists, and product formulators, it is possible to choose a sunscreen that’s safe for your body, safe for the planet, good for your skin, and above all, effective—and making the most informed decision comes down to understanding the differences between chemical and physical SPF. Ahead, the experts answer all of your (sun)burning questions.

First: Do You Really Need to Wear Sunscreen Always?

“Wear SPF” is a platitude so pervasive in the skin-care community that it’s a meme, and for good reason. Studies link excessive sun exposure to skin cancer and premature aging of the skin. That said, studies also link “sensible” sun exposure to optimal vitamin D levels, lowered blood pressure, and increased survival rates for other types of cancer. This second set of facts explains why countries across the globe, like the United Kingdom and Australia, recommend getting 10–15 minutes of sunlight per day sans sunscreen.

“[The average person should get] 10 to 15 minutes of midday sunlight several times a week,” says Dr. Aanand Geria, a board-certified dermatologist with Geria Dermatology in New Jersey, acknowledging that this is a bit of a “controversial” stance for a US dermatologist to take.

“No matter what amount of time you are in the sun, you should always wear sunscreen,” counters Dr. Zenovia Gabriel, a board-certified dermatologist known as Dr. Zenovia. You can consult with both your dermatologist and primary care doctor to determine the ideal amount of sun for you.

Yet even if you do decide to bask in the glow of the earth’s fiery life force for a full 15 minutes per day, that leaves roughly 945 minutes (not counting sleeping hours) of sun protection to consider. And for that, you have two choices: physical sunscreen or chemical sunscreen.

What’s the Difference Between Physical and Chemical Sunscreens?

“Physical sunscreens contain zinc or titanium dioxide and work by sitting on top of the skin and reflecting the sun’s rays,” Dr. Zenovia says. “They ‘block’ the sun’s rays from penetrating and protect your skin from both UV-A (aging rays) and UV-B (skin cancer rays) damage.” Physical sunscreen is also called “mineral sunscreen,” since the two active ingredients on the market—zinc oxide and titanium dioxide—are natural minerals.

In contrast, chemical sunscreens absorb the sun’s rays, “convert the rays into heat, and release them into the skin,” the dermatologist explains. This category includes avobenzone, oxybenzone, octocrylene, homosalate, octisalate, and octinoxate, among others. Chemical sunscreen is sometimes referred to as “synthetic sunscreen,” since these active ingredients are all man-made.

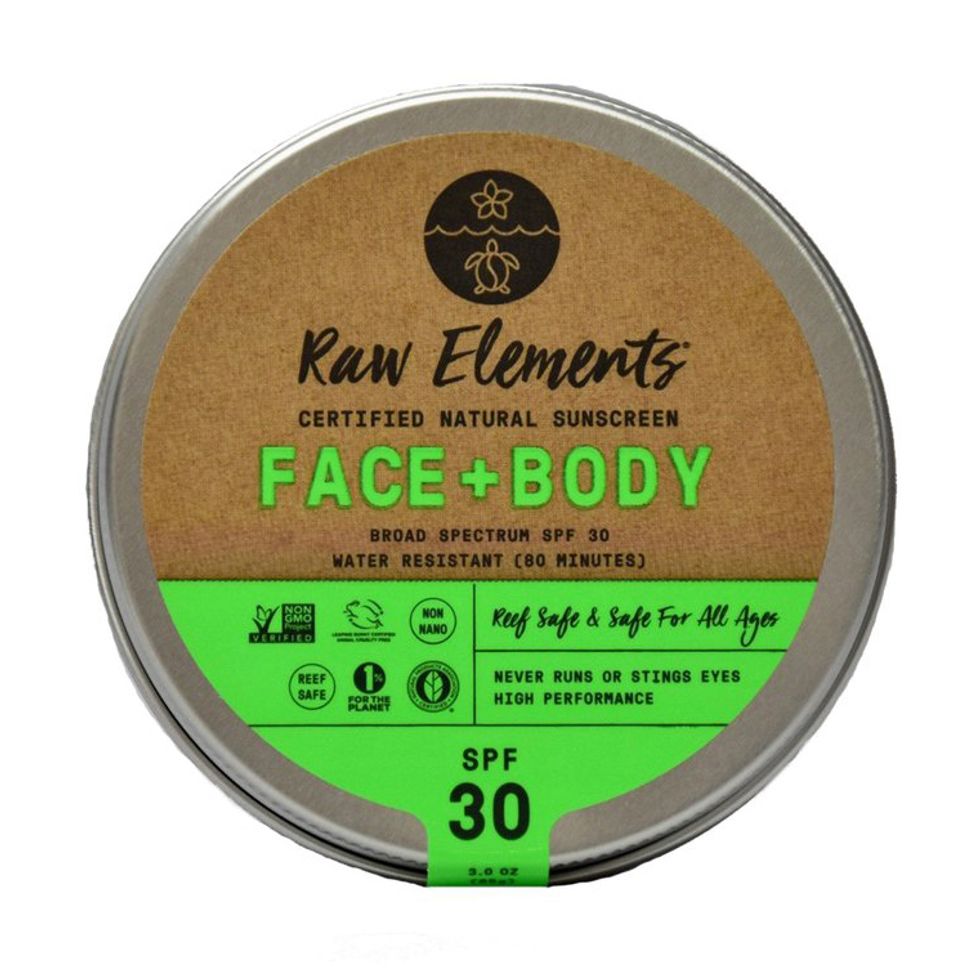

“Zinc oxide by itself blocks the full UV range,” Brian Guadagno, founder of Raw Elements, tells Coveteur, which is why it’s always the primary active ingredient (and often the only active ingredient) in physical sunscreens. Chemical sunscreen formulations, on the other hand, contain a cocktail of active synthetics, since each chemical sunscreen compound targets a different type of UV light (short-range UV-A, long-range UV-A, or UV-B). “Three or four or five chemicals together block the full UV range,” Guadagno notes. A formulation that shields against all types of UV light is considered a “broad-spectrum sunscreen,” the gold standard of SPF.

The History of Physical and Chemical Sunscreens

“Zinc oxide was the original sunscreen in ointments—think back to the white lifeguard nose of the 1970s,” Guadagno shares. But these early products were pasty, pricey, and, uh, really white, so the industry started searching for alternatives. “Moving towards the ’80s, the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries are asking, How can we make these formulas more lightweight, more aesthetically pleasing, shelf stable, and inexpensive? That’s when we begin to see the evolution of the chemical sunscreens.”

Chemical formulations reigned supreme for decades because “the [primary ingredients are] easier to formulate with and they’re much cheaper,” says Dr. Craig Downs, a forensic eco-toxicologist and the executive director of the Haereticus Environmental Laboratory. As with most things cheap and easy (plastic bags, Amazon Prime, makeup wipes), that convenience may come at a cost. “Now mineral sunscreens are coming back into favor because people are realizing the health implications and the environmental impact of [some of the] chemical sunscreens,” says Guadagno.

Physical vs. Chemical: Human Safety

The recent concern over the safety of chemical sunscreens largely stems from an early 2020 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The data collected by the FDA shows that six of the most prominent chemical actives—avobenzone, oxybenzone, octocrylene, homosalate, octisalate, and octinoxate—absorb into the bloodstream after a single application. When applied every two hours as directed, these ingredients appear in the blood at concentrations that surpass the FDA’s safety thresholds—meaning safety data has not been collected or analyzed at these levels prior.

“The data did not say that those ingredients are dangerous,” argues Dr. Nada Elbuluk, a board-certified dermatologist and clinical associate professor of dermatology at the USC Keck School of Medicine. (Absorption doesn’t necessarily equate to harm.) “We need more data about whether there are any harmful effects.” Particularly conscientious consumers are choosing to avoid chemical sunscreens until further research is conducted, just in case.

Other, older studies indicate that a handful of chemical sunscreens act as endocrine disruptors—that is, they interfere with the body’s hormonal system. “Oxybenzone has appeared in human breast milk, amniotic fluid, urine, and blood plasma,” says Dr. Zenovia.

“Oxybenzone is linked to [the birth defect of] Hirschsprung’s disease,” Dr. Downs adds, “and over 98 percent of the population can show that it’s in their blood or in their urine.” (The scientist notes that, “like secondhand smoke,” people who don’t personally use oxybenzone can still encounter the chemical via public swimming pools, where “the oxybenzone concentration can be in the parts per thousand, and you’re unknowingly absorbing it.”) Animal studies have linked octinoxate and homosalate to hormone disruption, as well.

While physical sunscreens have not been found to absorb into the bloodstream or negatively impact hormonal health, any sunscreen ingredient—physical or chemical—can be harmful if inhaled into the lungs via aerosol formulations (because sunscreen belongs on you, not in you).

Physical vs. Chemical: Environmental Safety

In 2008 Dr. Downs began investigating why the coral reefs in particular areas of the Virgin Islands National Park were dying. “We did some forensic eco-toxicology and found oxybenzone can be poisonous to coral reefs at the concentrations we were seeing,” the researcher says. That research helped inform the current legislation in the state of Hawaii and the city of Key West, Florida, which bans the sale of oxybenzone as well as octinoxate. “Oxybenzone causes deformities in the larval state of coral—the same thing as it does with humans,” Dr. Downs says. “Both oxybenzone and octinoxate cause DNA damage, so they’re genotoxic.”

A third sunscreen ingredient is now being looked at for its possible coral toxicity. “The science is becoming strong for a chemical called octocrylene,” Dr. Downs says, noting that the US Virgin Islands have already banned octocrylene.

Physical sunscreens are generally assumed to be reef-safe—but you know what happens when you assume, right? “Nanoparticles of zinc oxide and titanium dioxide can be harmful to wildlife, and there are a number of studies showing zinc nanoparticles can cause adverse effects in coral,” Dr. Downs says. “But once you get out of that nano size”—anything larger than 120 nanometers—“it becomes innocuous and non-toxic.”

This environmental research is relatively new and has faced its fair share of scrutiny and criticism from those who say climate change, not sunscreen, is to blame for the degradation of the world’s coral reefs. “That is not only fake news, that is intentional misinformation and propaganda,” according to Dr. Downs. Sure, other factors—pollution, human interference—certainly come into play. But “the research to date is fairly definitive that [these ingredients] are a distinct and clear and present threat to very specific coral reefs,” he says.

Alas, ensuring your SPF is eco-friendly isn’t as easy as buying a bottle emblazoned with the words “reef-safe.” The buzzy term isn’t regulated by any governing body, and therefore it can’t really be trusted. For now, scan the ingredient list yourself to make sure your products don’t contain oxybenzone, octinoxate, octocrylene, or nano-sized zinc and titanium dioxide. While you’re at it, eliminate any products that list “fragrance” as an ingredient. “Many fragrances are fortified with UV sunscreens, even oxybenzone,” says Dr. Downs. (Fragrance is considered “proprietary” under FDA regulations, so brands aren’t required to disclose the ingredients in their fragrance blends.)

Physical vs. Chemical: Irritation

“I have so many patients who say they break out or get a rash when they wear sunscreen,” Dr. Ebuluk says. Sound like you? Chemical sunscreens are most likely the culprit; when they absorb UV rays and convert them into heat, that heat has the potential to irritate the skin. “There is a subset of the population that can develop contact dermatitis, an allergic reaction to one of the ingredients in sunscreen,” the dermatologist confirms.

“For sensitive or rosacea-prone skin, I only recommend mineral sunscreens because they’re less likely to cause an immediate stinging or burning sensation,” Dr. Geria says. He adds that those using retinol or glycolic acid in their skin-care routine should look to mineral SPF as well, “since the ingredients are inert and won’t cause further irritation.” Fun fact: Zinc is the main ingredient in diaper cream, so you know it’s good at calming redness and irritation.

Physical vs. Chemical: Melasma

“I would definitely recommend a physical sunscreen if somebody has melasma,” Dr. Geria says. “This is primarily because physical sunscreens block ‘blue light’ that is emitted from our phones and computers, and blue light is capable of stimulating melanin production, which is the last thing you want if you have melasma.” (Blue light is also emitted by the sun, FYI.)

In other words, chemical sunscreens do not protect against blue light (which is a form of visible light, not UV light), but physical sunscreens do. For this reason, Dr. Ebuluk advises her melasma patients to “layer a physical blocker” on pigmentation-prone areas of the face and body “even if they’re using a chemical sunscreen” all over.

Physical vs. Chemical: Effectiveness

All of the above points mean nothing if your SPF is lacking in the PF department (that’s Protection Factor, of course), and a 2019 study from the Environmental Working Group showed that an astounding 60 percent of sunscreens tested did not offer the advertised sun protection. So what’s going on here? “Chemical sunscreens break down with UV light, making them ineffective,” Dr. Zenovia muses. “Reapplication [every two hours] is paramount.”

Zinc-based physical blockers aren’t necessarily better. “Any acidic sunscreen will cause zinc oxide to dissolve into zinc, so you lose your SPF,” Dr. Downs explains. “And most manufacturers aren’t pH-balancing their products.” He recommends purchasing pH strips to test sunscreens yourself, since most brands don’t share (or perhaps aren’t aware of) the pH levels of their goods. “Put a little dab on the pH paper, and if it’s below a pH of seven, I wouldn’t trust it, because it’s acidified,” he says. “If it’s anything below six, you’re going to start dissolving the zinc oxide, and that’s not a safe product.”

Physical vs. Chemical: Wearability

Non-nano, pH-balanced zinc oxide is far and away the experts’ top choice for a safe, effective, eco-friendly, and skin-loving sunscreen. However, there’s one area where the physical blocker still lags behind, and that’s wearability—specifically, wearability for Black and brown skin. (And yes, dermatologists maintain Black and brown skin does need daily sun protection.) Tinted, blendable zinc formulations are becoming more common nowadays, but “mineral sunscreen has historically had more of a thick, white, pasty look,” Dr. Ebuluk says.

“Just like in other industries, darker skin has been left out [of the sun-care space],” Shontay Lundy, founder of Black Girl Sunscreen, tells Coveteur. “It’s an afterthought.” After struggling to find a safe SPF product that didn’t leave behind a chalky, ashy residue, “I thought to myself, ‘I can’t be the only Black girl who’s looking for a sunscreen that applies evenly.’” This was the aha moment for Black Girl Sunscreen. “We went with a synthetic approach, since it’s easier to remove that whiteness,” she says.

Currently, the brand formulates with avobenzone, homosalate, octisalate, and octocrylene—but a physical, zinc-based formula is on the horizon. “With sun care, you have to speak to all, and synthetic doesn’t speak to all,” Lundy explains. “People have different values when they’re selecting products, so we have some exciting things coming that will incorporate zinc.”

The Final Word

“What’s most important to me is that people are wearing sunscreen, period,” Dr. Ebuluk says. “Which type you decide to use, physical or chemical, is a personal preference.”

Below, an array of sunscreens to protect you from the damaging effects of the sun.