Rosalía's "LUX" & Fashion's Religious Awakening

In a world of AI and algorithms, the singer's fourth album leans into something raw, devoted and unmistakably human.

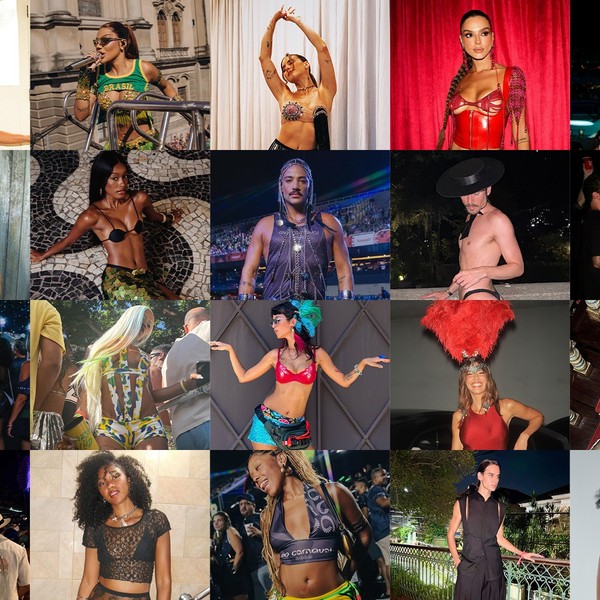

It’s been roughly two weeks since Rosalía brought her fourth studio album, LUX, into the world. Steeped in beatification and religious references, LUX immediately demanded our full attention. Throughout the album, she sings in13 languages, accompanied by the London Symphony Orchestra, with lyrics referencing transcendence, rebirth, religion, heaven and divinity. In listening to LUX, watching the music video for Berghain, and witnessing Rosalía’s style as she engages in press for the album release, I’m reminded of how deep the link is between religion and fashion throughout history, and all the ways the Roman Catholic Church plays within fashion’s lexicon.

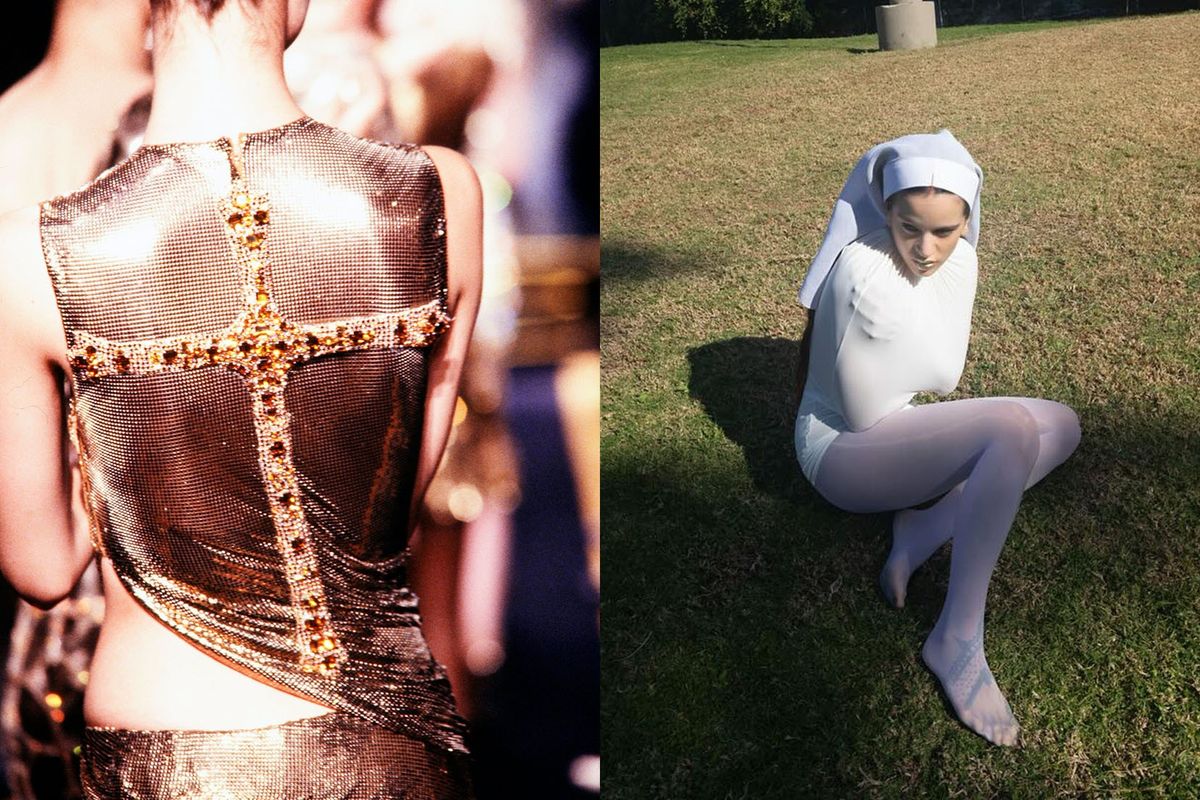

In a noticeable shift from her previous albums, Rosalía’s LUX aesthetic is distinctly religious. On the album cover, styled by Chloe & Chenelle Delgadillo, she is swathed in whites, her arms restrained under clingy fabric—complete with a nun’s veil. The Noah Dillon-lensed promo images feature the Catalan pop icon with prosthetic, skin-like rosary beads that twine up her wrist like a body modification, dove wings covering her chest, her fingers dipped in gold. In one image, she wears a white tulle dress in the ocean to symbolize purification; in another, she perches by a fire naked, a bleached halo highlighted in her hair that falls biblically around her shoulders, shrouding her body.

Constraint and prayer are common themes throughout the album artwork, whether she’s wearing a pair of 2004 Jean Paul Gaultier lace gloves, or donning a pair of Alexander McQueen Spring 2003 heels featuring rosaries that wrap around the ankle in the music video for “Berghain.” This specific collection from McQueen was laden with religious themes, as so much of Lee McQueen’s work was; it’s no surprise the singer has been wearing pieces of it throughout her press tour. Just the other day, she was seen in a paparazzi photo wearing another silk blouse from the 2003 collection with rosary bead straps, a cross hanging from her neck as she walked through the streets, the bleached halo in her long, wavy hair glowing in the sun as fans gathered around her—a scene that was practically Biblical.

Getty Images

Many of the references on the album are inspired by the lives of female saints. Rosalía uses their stories to reflect on her own, including that of Rabia Al Adawiyya, widely considered the first female Sufi saint in Islam and the reference point on the track, “La Yugular.” Al Adawiyya’s guiding principle is the doctrine of divine love, which teaches loving Allah for his own sake, seeking to destroy Hell and Heaven so that devotion comes from pure and selfless love. Here, Rosalía explores divinity by affirming her commitment to something bigger, and through her romanticism of devotion throughout “LUX”.

Getty Images

This sense of devotion is not only prevalent in religion, but in fashion culture at large with the reverence we have for the cult designer, romanticism and the female body—all of which are used to draw out emotion from the witness. Within this framework, Catholicism and religiosity sits at the apex of fashion’s larger storytelling tradition.

Many designers who have experimented with religious codes throughout history were raised Catholic themselves. Elsa Schiaparelli, John Galliano, Riccardo Tisci, Christian Lacroix and Coco Chanel come to mind. McQueen’s take on religion was slightly more macabre, while Dolce & Gabbana’s designers built a brand off the back of references to the church. Lee McQueen’s relationship to religion was a constant fascination, but no more squarely than in his Fall/Winter 1996 show, entitled “Dante, which was held at Christ Church, Spitalfields. The collection itself was filled with Victoriana references, slashed admiral jackets and masks with crucifixes. Later, McQueen criticized the church, telling WWD, “I think religion has caused every war in the world, which is why I showed in a church.”

Christian Dior Couture F/W2000

Getty Images

Alexander McQueen F/W 1996

Getty Images

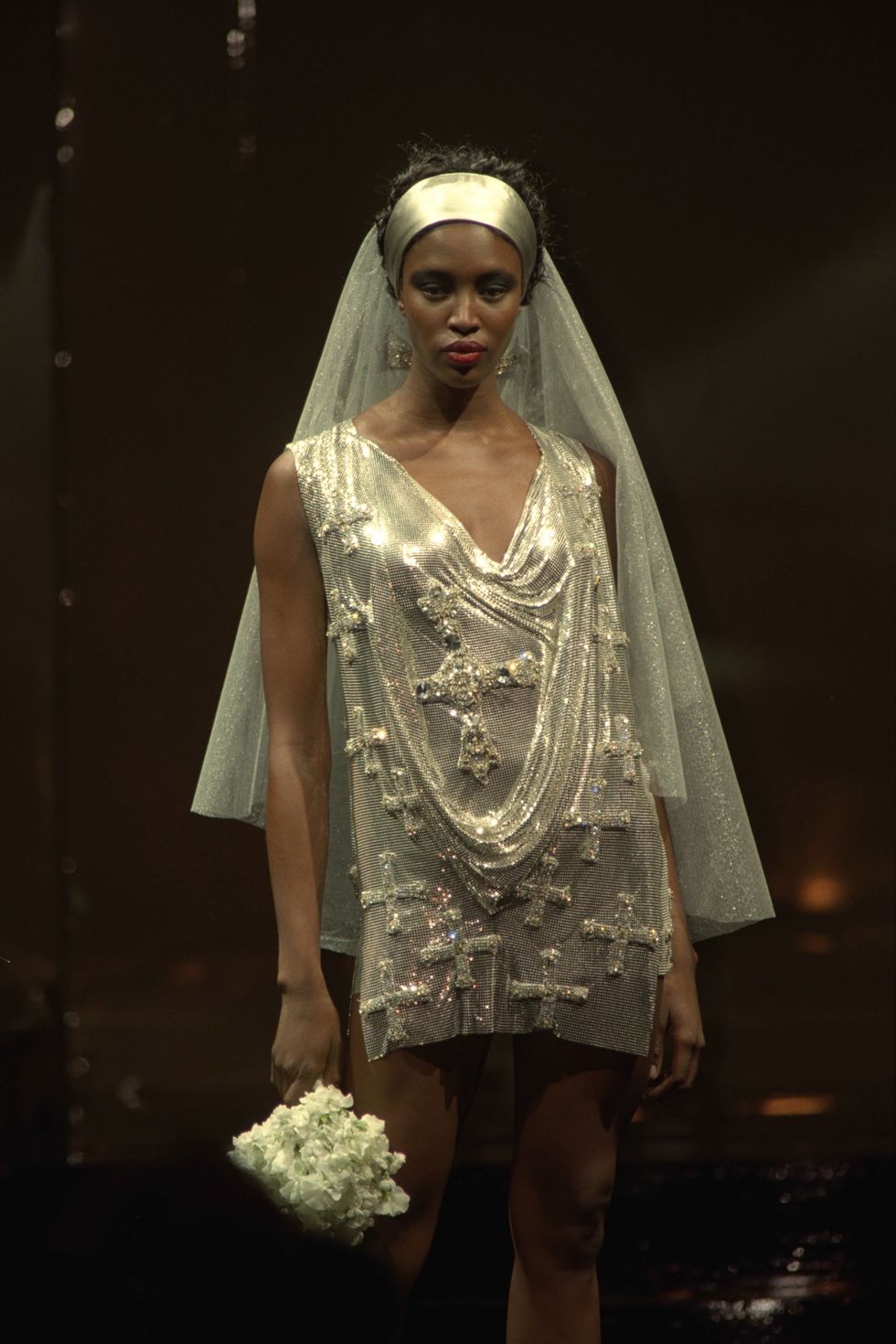

John Galliano was another designer who used religion to explore the role of costume and identity in design. Specifically, his Fall 2000 Haute Couture collection for Christian Dior, where he sent a model down the runway wearing a Catholic priest costume, which was later acquired for The Met’s 2018 exhibition, Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination. Then there are the Italians, like Gianni Versace and Domenico Dolce & Stefano Gabbana. The former showed a final collection just a week before his death, featuring pieces inspired by the mosaics at cathedrals and glo-mesh gowns with crosses embellished onto them. The latter were similarly inspired by Byzantine and Venetian mosaics for their Fall 2013 show.

In fashion, religious references tend to surge as a direct reflection of global uncertainty. We saw major waves in the 1990s—when Madonna released her seminal “Ray Of Light” album, working closely with designers like Olivier Theyskens and later Christian Lacroix, Jean Paul Gaultier, and Versace to juxtapose shiny leathers and conical bras with the crucifixes that became so synonymous with her early look—and then again in 2020, during a pandemic at the peak of modern global uncertainty, Five years on from our last religious boom, the Catholic imagination resurges in another time of political and social tumult—tension that’s sharply communicated in 2025’s “LUX,” as well as the runways.

Versace F/W 1997 Couture

Getty Images

Dolce & Gabbana F/W 2013

Getty Images

For Spring/Summer 2026, McQueen’s Sean McGirr brought back the rosary bead shoe from 2003, only this time replacing the dangling cross with a wishbone instead. Anthony Vaccarello’s models for Saint Laurent wore baroque, oversized gold cross earrings dripping with pearls and resin beads, while Maria Grazia Chiuri’s final Dior couture show featured overt religious symbolism, from the Vatican-inspired cape dresses to vestment-like white shirts.

Here, these references examine the Catholic church’s propensity for storytelling, and for not only the narrative level of which religion exists, but the experiential, too. Designers use techniques that mimic stained glass windows and the ornate, Byzantine architecture of ancient places of worship. Rosalía’s synthesis of these pious themes through each touchpoint of “LUX’s” release—from the sanctimonious quality of the music to her fashion direction—only further this point, and indicate that we’re in for a religious boom within the fashion lexicon once again.

Saint Laurent S/S26

Getty Images

But there’s another layer this time, too. In an interview with Zane Lowe, Rosalía talks about “LUX” as “a human album,” in reference to the distinctly anti-AI approach she had to the production of the record, as a response to much of the mass-produced, non-complex TikTok viral music that is charting today. With this in mind, the complexity of religion feels like the perfect antidote to an increasingly over-simplified industry. When a subject-matter is so vastly rich in text, transcending time and culture, it’s easy to find meaning. Collectively, we’re finding ourselves in a moment where what we are craving is alive, human. When viewed through the lens of fashion, we pine for rich storytelling, steeped in reference and evoking real feelings.

When viewed through this lens, we all could use some faith right now, some devotion. We are existing in a paradigm where everything is digestible, sped up, boiled down and simplified for optimal psychological digestion. Why ask for a backstory when everything is TLDR? When the digital age makes everything look and sound the same, algorithmically optimized but lacking soul, devotion to something, or someone, is what separates us from machines. And what better way to return to human art than through text so ancient it has no choice but to be inherently man-made? This is what we are reminded of when fashion and art references something so steeped in history, so charged with narrative and emotion and even conflict—a lifetime of it, no less. Catholicism, religion, and religious institutions are not without their criticisms. And yet, the art born from them reminds us: if it doesn’t stir something in you, was it ever worth looking at?