The Story Behind Maybelline’s Most Popular Mascara

Great Lash has been a staple in makeup bags for more than 50 years—here's why.

The "Romantic Lie" is what French socialist René Girard calls the assumption that everything we desire comes from the heart. It's the idea that desire is independent and isn't swayed by the opinions of others.

This is, of course, false. According to Girard, our desires are mimetic, meaning that they are shaped and influenced by the choices of the people around us. Girard calls them models. According to Luke Burgis, the author of Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life, models of desire are "people who we look to for guidance about what to want (usually without knowing it)." And then, there's metaphysical desire—the desire of someone else's desire. It has nothing to do with a specific object, like a car or a house, says Burgis. "It is concerned with being a certain way. It is concerned with identity."

Glamour could be considered a metaphysical desire. According to Virginia Postrel, author of The Power of Glamour, "glamour is not something you possess, but something you perceive." It's the fantasy of someone else wanting you and it gives you the illusion of power.

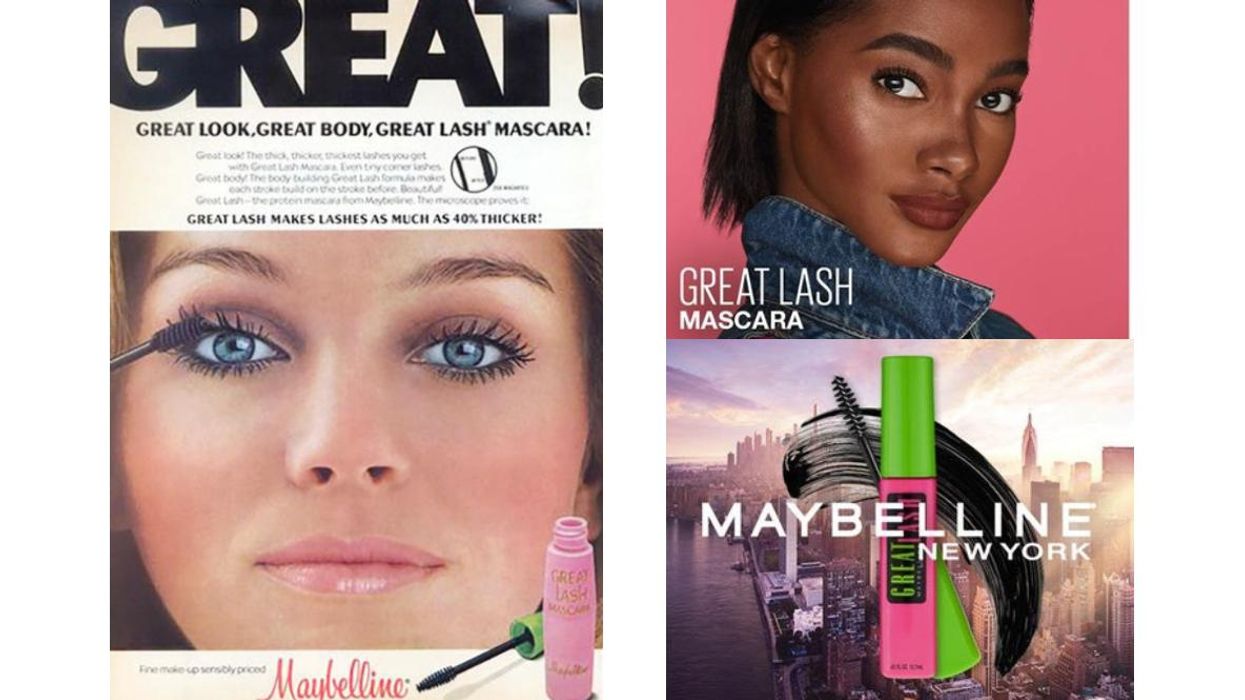

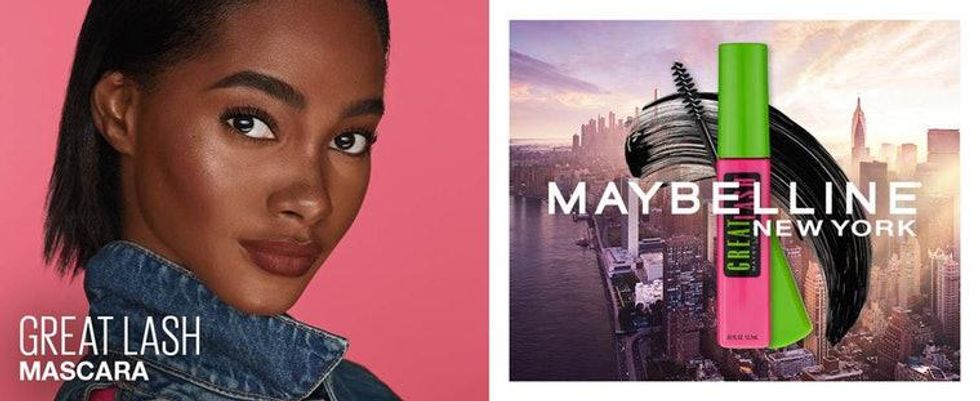

When Maybelline's Great Lash mascara launched in 1971, all of these factors were in play. The mascara was an instant hit, says Jessica Feinstein, the senior vice president of marketing at Maybelline New York. Fifty years later, it's still one of their best-selling products. The beauty industry has boomed as of late, and every other day, it feels like three new brands pop up. In such a saturated market, how exactly has Maybelline's Great Lash remained so culturally relevant?

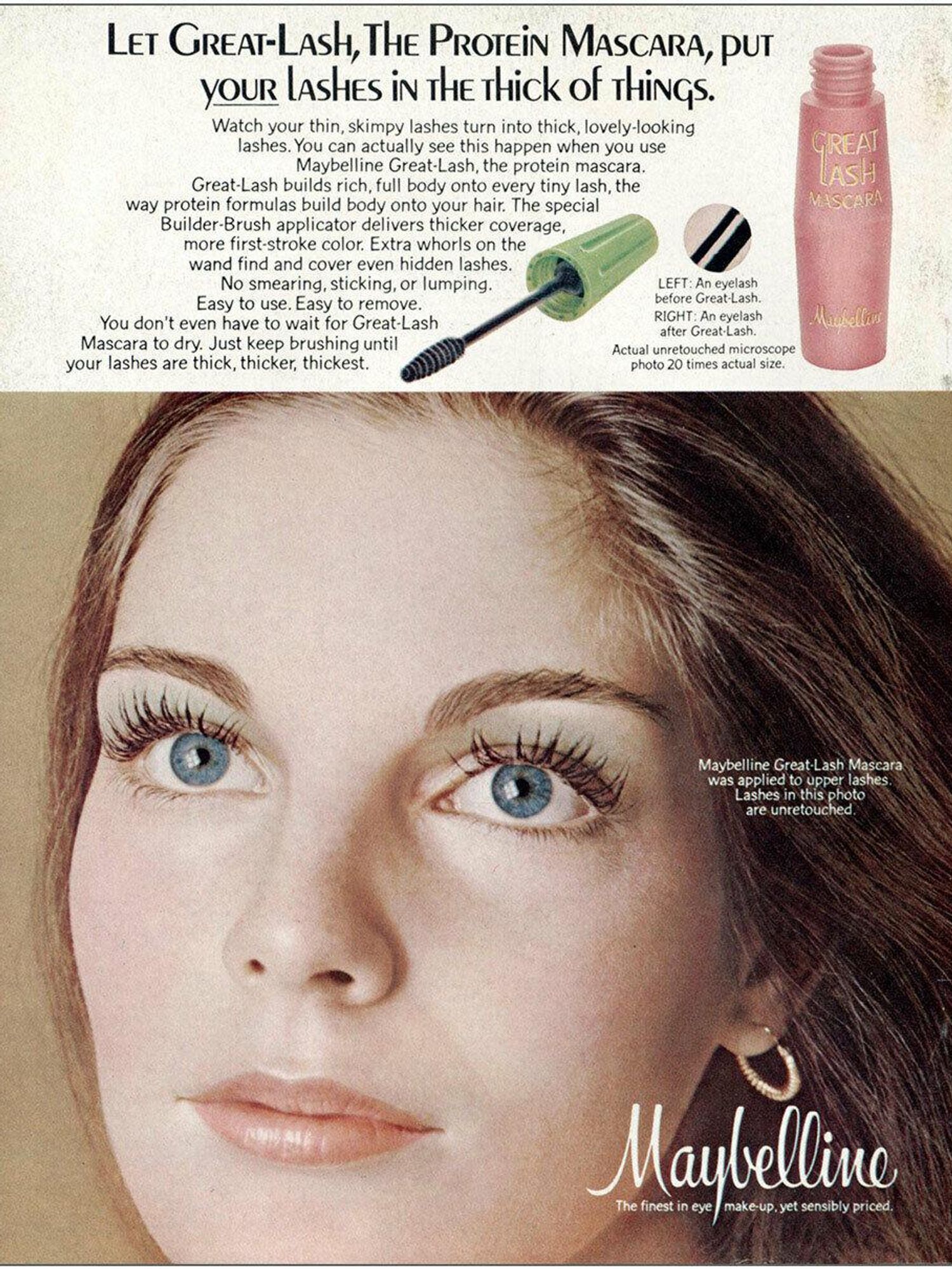

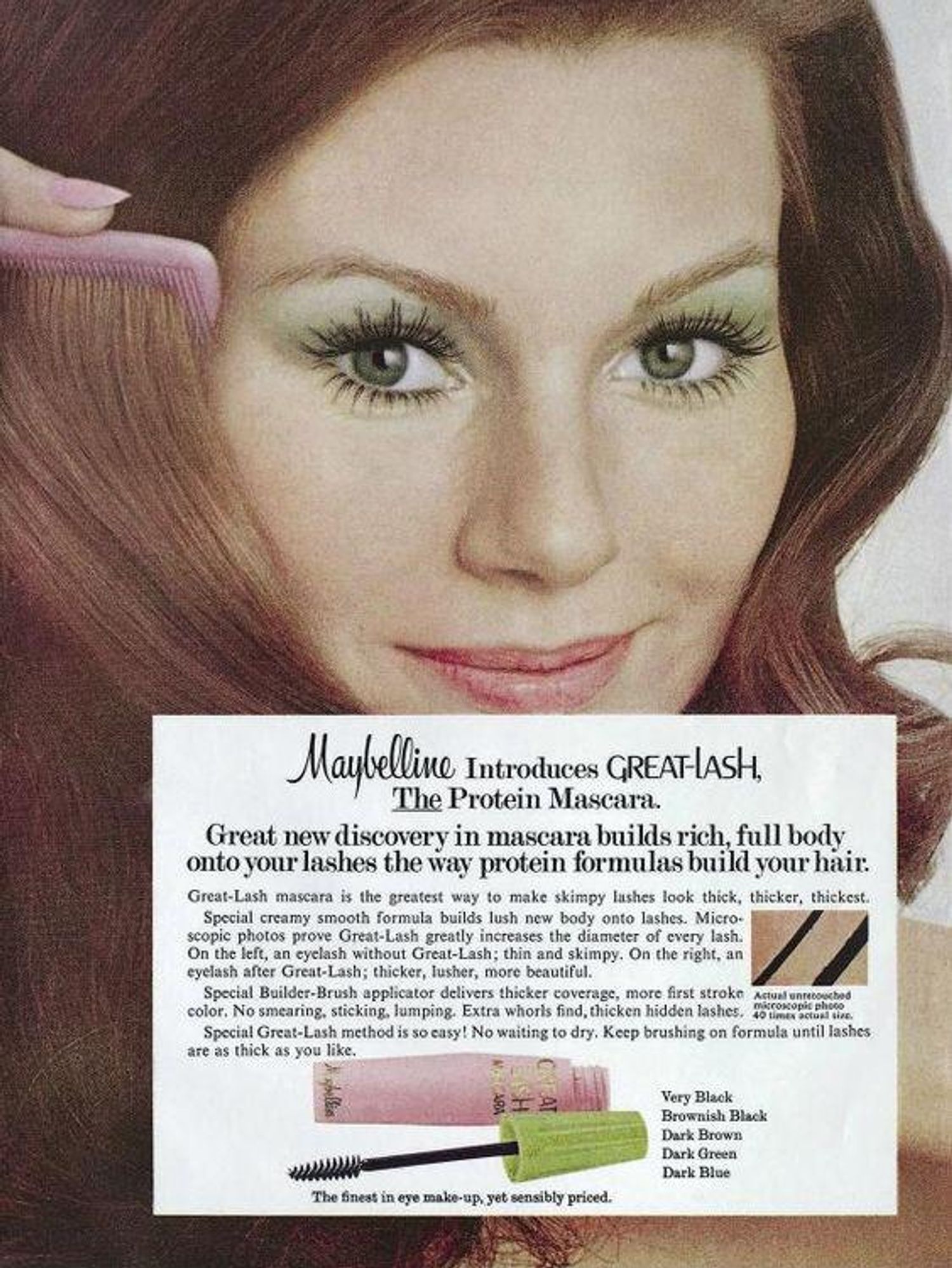

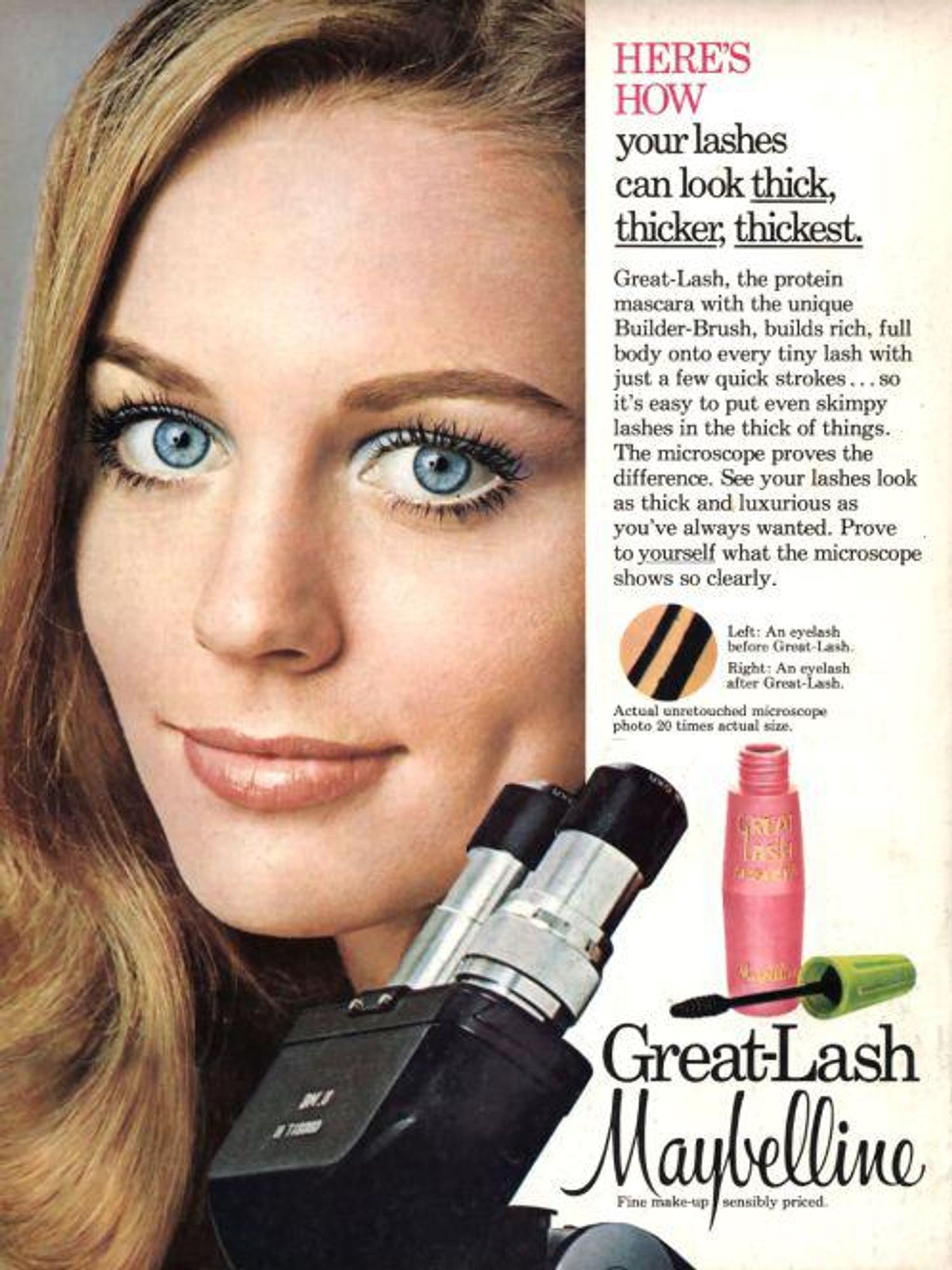

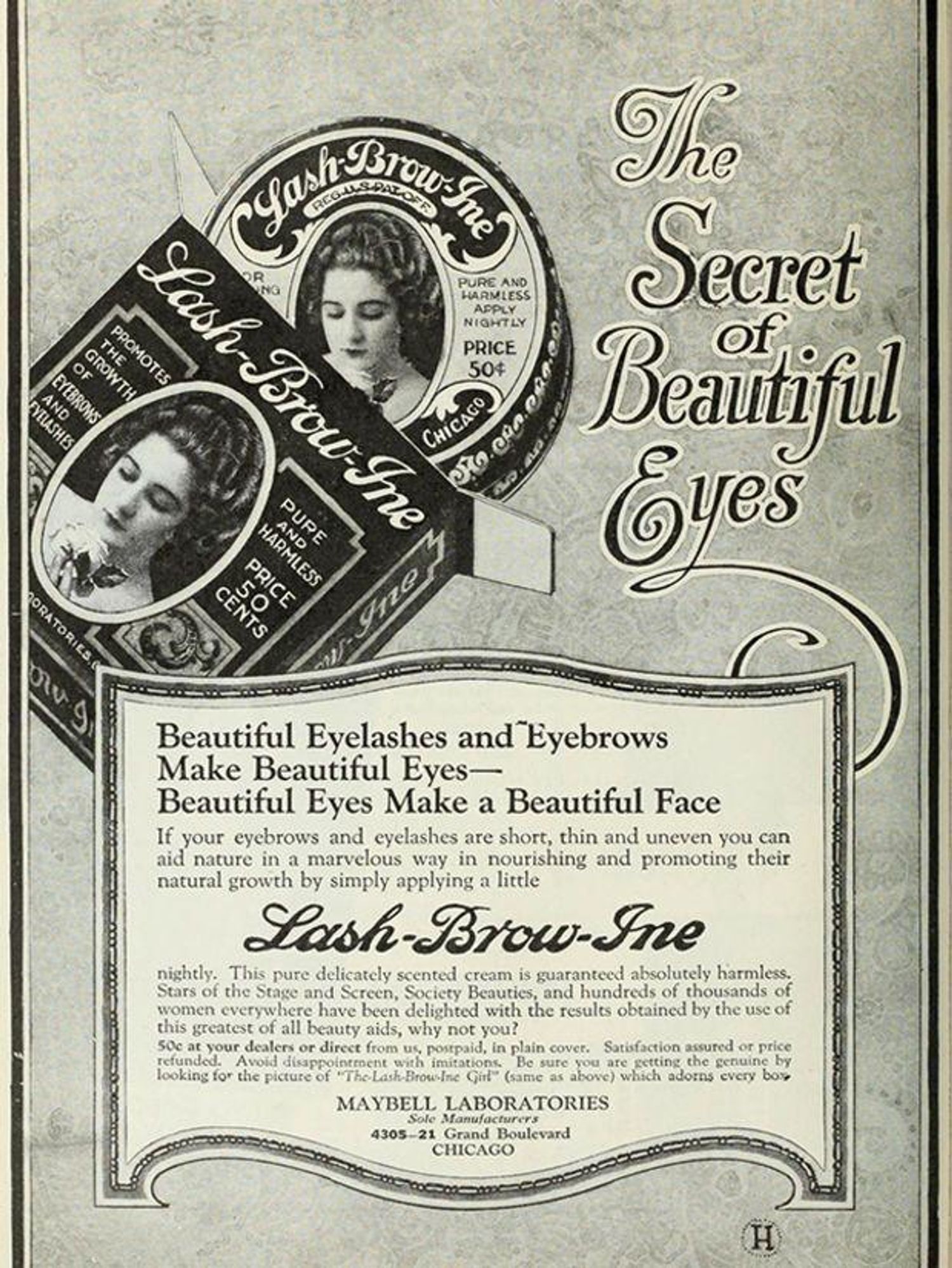

Artists from the Victorian era painted their women with ridiculously lengthy lashes and by the 20th century, the idea of using mascara to enhance one's fringe was growing in popularity in the United States. As the story goes, in 1915, Thomas Lyle Williams, a Chicago entrepreneur, noticed his sister Mabel mixing Vaseline and coal dust to darken her lashes. Inspired to create a product that would enhance lashes without the do-it-yourself effort, Williams developed a cake mascara that came in two parts: a goop of mascara product and a tiny brush. He began sending out orders and named his company Maybelline, after his sister (Mabel) and her go-to beauty product (Vaseline). Decades later, Great Lash was introduced. "It was the first water-based automatic mascara," says Feinstein, "making it much easier to remove than other mascaras at the time, which were wax-based."

The boom of Maybelline's mascaras was set against the backdrop of the rise of media and Hollywood. By the 1940s, cinemas and celebrities were everywhere. "Movie theaters reached almost every American town," writes Geoffrey Jones in Beauty Imagined, "diffusing new lifestyles and creating a new celebrity culture around movie stars that exercised a powerful influence on how beauty, especially female beauty, was defined." Actresses on the silver screen wore eye makeup for their roles and women watching in their hometowns began to mimic the looks they saw on movie stars like Joan Crawford and Merle Oberon. The '50s also saw the use of star power and new advertising forms to influence the desire for darkened lashes. "The first makeup commercials people watched over their TV dinners were Maybelline commercials," says Feinstein.

Models of desire transform objects right before our eyes. Burgis describes how it works, below:

"Say you walk into a consignment store with a friend and see racks filled with hundreds of shirts. Nothing jumps out at you. But the moment your friend becomes enamored with one specific shirt, it's no longer a shirt on a rack. It's now the shirt that your friend Molly chose—the Molly who, by the way, is an assistant costume designer on the sets of major films. The moment she starts ogling one shirt, she sets it apart. It's a different shirt than it was five seconds earlier, before she started wanting it."

It's the same case with mascara. The desire to look a certain way or use a certain product is never truly our own; the influence of others we admire or respect plays a significant role.

The economic conditions of 1971 certainly helped as well. "Any society in which people are no longer struggling with scarcity but coping with abundance will undergo an explosion of mimetic desire," says Burgis. In that same year, the first Walt Disney theme park launched, Starbucks opened its first store, and Nike's signature swoosh was created. Think of those three brands—they each have a logo that's probably imprinted in your memory. There's several factors considered when it comes to branding, but for Maybelline's Great Lash, color psychology was key.

Complementary colors—opposite colors on the color wheel—transform ordinary objects into ones that grab your attention. Together, the two colors create a visual tension that's eye-catching and draws in the viewer. The complementary color of pink is lime green.

The choice in color combination was also inspired by Lilly Pulitzer, says Feinstein. Pulitzer was a model of desire herself and her brand was a status symbol that represented something that money cannot buy, regardless if you're able to procure the clothes, or in this case, the mascara. It represented the illusion of glamour, a metaphysical desire that remains elusive. It's not an object we want so much as we want the life it promises.

*

Long lashes open the eyes, evoking both mystery and invitation. The doe-eyed effect of lengthy fluttery lashes is tied to "babyfacedness," which is linked with "personality traits such as honesty, straightforwardness, warmth, naivety, and kindness." Babyface enhances the allure of qualities that are thought of as feminine, increasing one's beauty currency and attracting male attention.

In Deceit, Desire and the Novel, Girard states that "to imitate one's lover's desire is to desire oneself, thanks to that lover's desire. This particular form of double mediation is called 'coquetry.' The coquette does not wish to surrender her precious self to the desire which she arouses, but were she not to provoke it, she would not feel so precious." According to Nancy Ann Rudd's thesis in Cosmetic, Consumption, and Use Among Women, the glamourized ritual of buying a mascara, applying it, and stoking desire within others and yourself gave women a way to "enhance personal identity construction" while giving them an individual sense of "cultural power and social agency in a postmodern world."

Mimetic desire begets mimetic desire. An in-house Maybelline study showed that around 13 percent of social posts about Great Lash mentioned its iconic status. "Great Lash Mascara is one of those products that gets passed down from generation to generation," says Feinstein. "The iconic pink and green tube is a staple in your mother's, grandmother's, sister's beauty kit, and elicits special stories about the 'first' product you bought and used."

Iconic brands remain that way because of their ability to construct a connection with the culture. Even though Maybelline's Great Lash mascara performs well, that is not what gives it that emblematic value. It's what the brand stands for that does the work. Those abstract ideas are delivered to us in the form of a bright green and pink tube and they are enhanced by the ideology surrounding it.

Rather than falling apart due to changing cultural tides over the last 50 years, Great Lash has only grown stronger. Its myth is tied to family legacy, the significance of passing down an object through generations, and glamour. These are values intertwined with the brand and with each swipe, there's the trace of hope that we'll be able to reincarnate them for ourselves.

Photos: Courtesy of Maybelline New York

Want more stories like this?

An Ode to Lil' Kim's '90s Over-the-Top Beauty Looks

The Summer Read That Dissects Narcissism, Desire, & Love

An Ode to Tom Ford's Gucci and All the Glamour That Entails