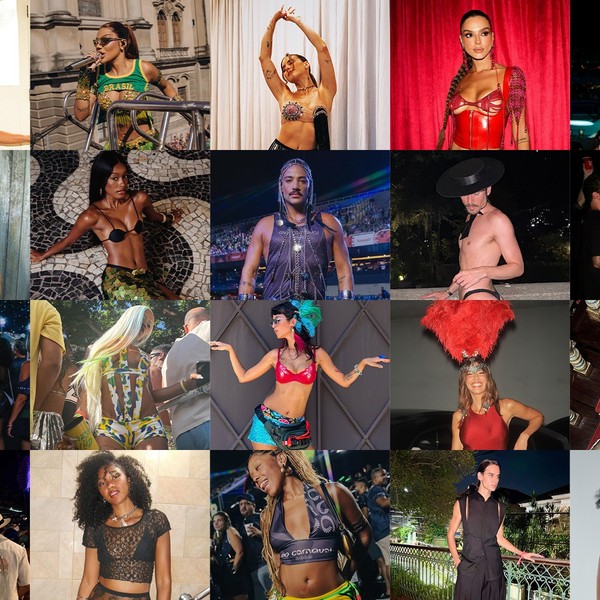

What Happened To Instagram Face?

The newest aesthetic trend of 2026 is sending a different message.

A TikTok video recently went viral in which a woman urged people to “keep your lower bleph.” In the clip, she cites Léa Seydoux, Kristen Stewart, and Sky Ferreira, arguing that under-eye bags are “French” and what makes these women uniquely sexy. The implication is clear: what was once considered a flaw is now the new ideal.

We’re existing in a moment in time where plastic surgery is increasingly accessible, increasingly trendy, and increasingly liberal. At first, it was the upper blepharoplasty—the cosmetic eyelid surgery that removes excess skin from the upper eyelids—that made the rounds on TikTok, as more women openly documented their journeys and recoveries. Then, it was the full, deep-plane facelift: one woman went to Guadalajara to get hers and practically broke the internet documenting her recovery. Rhinoplasty “unboxings” soon followed, vlogged with the same casual feel of a skincare haul.

Since Jia Tolentino coined the term “Instagram Face” for The New Yorker in 2019, there have been countless think pieces and op-eds dissecting the rise of facelifts, blepharoplasties, and rhinoplasties in order to achieve the look. She describes it as “a young face, of course, with poreless skin and plump, high cheekbones…catlike eyes and long, cartoonish lashes…a small, neat nose and full, lush lips...distinctly white but ambiguously ethnic,” a combination of generic celebrity features flattened into a replicable template.

But just as quickly as society settled on “Instagram Face” as the beauty standard of the 2020s, things have begun to shift, ever so slightly, back in favor of uniqueness. But is Instagram Face really over, or has it just evolved?

Social Media & The SHEconomy

Raphael: La Fornarina

Shutterstock

The American Consumer Council has stated on its website that women account for 80% of consumer purchasing, naming them “the most powerful consumers on the planet.” This is not because women have more disposable income than men, but because for decades upon decades, the beauty-industrial complex has told us that the relentless pursuit of aesthetic perfection that befalls women is futile if we do not purchase the right tools, the right treatments, the right products, surgeries, and memberships. The SHEconomy, coined in 2007, tracks the global rise of women as major consumers and economic drivers.

An inferiorized woman is the perfect consumer. What better way to subjugate women into being economically and socially controlled than to indoctrinate her into consumerism by repackaging it as “self-care”? Social media has been the SHEconomy’s most effective delivery system over the past decade, and the proof lies in the fact that Gen Z women are spending a significant amount more on beauty products and procedures than any other demographic. While some may feel as though social media’s oversharing habit has offered transparency, it has also democratized and desensitized us to said treatments, making them seem as simple and accessible as a trip to the dentist (some are literally easier and less uncomfortable).

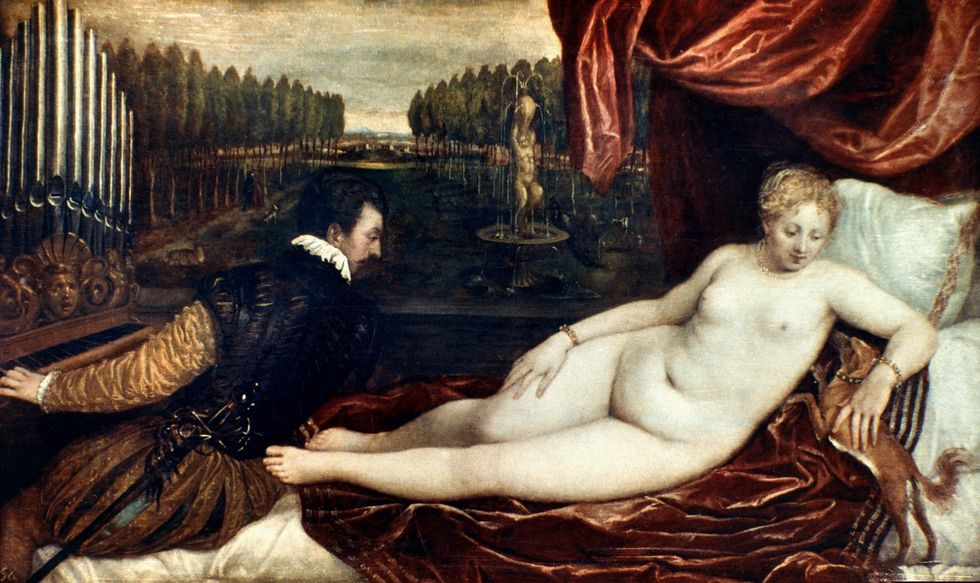

Beauty Standards As A Moving Target

Titian: Venus. 'Venus Amusing Herself With Music' By Titian

Shutterstock

Melinda Farina, best known as The Beauty Broker, is a NYC-based consultant who works with patients to pair them with their ideal surgeons and aesthetic doctors—like a beauty matchmaker, if you will. “The homogeneous face is losing cultural relevance,” Farina says. “We’re seeing a return to honoring bone structure, familial traits, and individuality. Beauty is moving away from templates and toward specificity.”

Dr. David Shafer, MD, FACS, a double board-certified plastic surgeon in NYC who specializes in all aspects of aesthetics and cosmetic surgery, agrees that unique features are on the rise. In recent years, he’s noticed an influx of clients who are asking for a more natural look and asking to dissolve their filler—but not for the purpose of going au naturel. Instead, he notes that his clients who have been “filling, filling, filling” are waiting for their filler to dissolve so they can “start over and take a more refined, sophisticated approach.”

“What's happened over the last 10 years or so is the understanding of the anatomy of the face—how aging works, how different areas of the face sagging can affect another area of the face,” he says. “[As a result], so fillers have become much more sophisticated and targeted, almost with surgical precision.” In other words, the rise of individuality doesn’t necessarily mean we’re embracing our natural features—we’re just altering ourselves in a more believable way.

The capriciousness of the beauty standard is the culprit of this slight change in the aesthetic wind. It’s important to note that while our attitudes seem to be vaguely shifting towards “uniqueness,” our attitudes towards spending money and time to achieve this have not. Beauty standards have to change and evolve to keep women invested in the idea of self-betterment. Where BBLs were trending five years ago, today’s beauty standard indicates that they are not, encouraging plenty of women who paid thousands of dollars to undergo the dangerous surgery to look into removing or reversing their procedures. Eye bags may be temporarily “hot,” but women are now doing tutorials on how to accentuate them with makeup. “Big” noses might be considered more charming—Bella Hadid made headlines for speaking out about regretting her nose job at age 14—but where does that leave all of the girls who paid for their itty-bitty, post-surgery Bella Hadid noses?

Last year, I noticed girls on TikTok were vlogging themselves dissolving their lip filler. Each of these women would document themselves with white numbing cream spread across their mouths, their swollen and bruised lips directly after the procedure, and a reveal 24 hours later, debuting their new (old) lips. How liberating! The comments section was filled with affirming notes about how much more beautiful and unique these women looked. Not long after, many of these TikTokers would log back on and report to their followers that they were still getting a “tiny bit” to fill their lips back up.

Notes On Choice Feminism

Jayne Mansfield

Shutterstock

Choice feminism argues that any choice a woman makes is inherently empowering. By this metric, it should be our empowered decision to say and do what we please with our bodies and faces. But what choice feminism fails to acknowledge is the ways in which women are both consciously and subconsciously influenced by the systems they live under on a daily basis. Choice feminism would only work if the choices we were presented with were made from a position of equal freedom and access/awareness. When we live in a society that is still propped up by not only patriarchy, but the systemic injustices that require intersectionality to exist, choice feminism cannot exist in a vacuum.

I got 0.4ml of lip filler when I was 25 years old. Instantly, I felt sexier. I couldn’t afford the nose job I actually wanted at the time, so I decided on the cheaper option of “facial balancing” to make me more comfortable with my profile. It worked. But I do wonder how I would feel now about my non-surgically altered face if we were still hurtling towards a more homogenous look. Would I still want that rhinoplasty? All of the tiny, mostly undetectable tweaks I have made to my face in the past five years make me feel better, more confident—not different or unrecognizable—just…hotter by traditional standards. I wouldn’t choose to stop doing them in the name of bucking against the beauty industrial complex—I am far too aware of the space women are more likely to claim when they feel good about themselves and, frankly, far too vain to act as though looking “good” (by traditional metrics) doesn’t matter to me. But to fail to acknowledge the ways in which both patriarchy and media have influenced these choices would be to surrender to these exploitative systems fully under the guise of choice.

Uncanny Valley

Sophia Loren, "The Pride and the Passion" (1957)

Shutterstock

As these procedures become more refined and injectors become more adept— like Dr. Shafer, who notes that good injectors blend technical skills with artistry for a “sophisticated and natural result”—it can feel like doing small tweaks to your appearance is simply the norm. At best, it can boost self-confidence and democratize the industry with fairer prices that make injections more accessible. At worst, it can desensitize all of us to perfectly altered faces that look natural, but are the result of carefully-placed syringes.

I’m not sure I’ll dissolve my lip filler any time soon, even though I obsess over the potential unwanted migration that might give away the fact that my pout isn’t 100% my own flesh and blood. I get Botox in my forehead once every four to six months (Dr. Shafer says every three months is ideal), not because I'm scared of looking old, but because I feel my most “snatched” at the three-week mark when it has fully taken effect. My skin glows and my eyebrows lift the extra skin off my hooded eyes just enough to make me look less tired but not changed. I am still grateful that I have access to the treatments that have made me more comfortable within myself, even if the question remains: am I genuinely comfortable with myself if it’s a different version of myself that I am most comfortable with?

If the age of Instagram Face is just evolving instead of waning, where are we left in terms of navigating aesthetic tweaks and surgeries from a social and political perspective? Ultimately, any move from a homogenous look in the direction of a more amorphous one is, surely, a positive step on the path of liberation.