If you are plugged into fashion discourse, you’ve probably heard about High Sport Kick Pant by now (perhaps against your will). They are stretch ponte trousers with a cropped flare above the ankle and pleats down the center of the legs. Sturdier than leggings and distinctly more polished. The intrigue around these pants reached a fever pitch on Substack in late 2023 - early 2024. The Kick Pant has developed a cult following, but skepticism has started to mount.

Substack, the newsletter platform, is integral to the phenomenon of High Sport. It’s where fashion influencers and ex-editors with large followings raved about the pants to their readers. Several glowing endorsements were published within a short time span. Word spread like wildfire within the platform’s ecosystem. Substack writer Rachel Solomon of Hey Mrs. Solomon describes the High Sport pants as a “fireball” item that seemed to “materialize out of nowhere.” She believes the hype is tied to the inherent “miracle potential” of pants, which are extra compelling because “the ass/thigh area is so important when it comes to fit and use case.” People will pay a lot for pants that make their butt look good.

“The chatter about these pants on Substack chat was non-stop,” says the writer of Totally Recommend, a self-described “recovering marketing CEO” who goes by Rufina. Her assessment of the situation? It seemed like no one beyond fashion writers and influencers actually owned the High Sport pants, yet everyone was hunting for alternatives. “I realized we were all searching for dupes without even knowing what the originals were truly like. That's when my curiosity really kicked in. I knew I had to get my hands on these pants,” Rufina states.

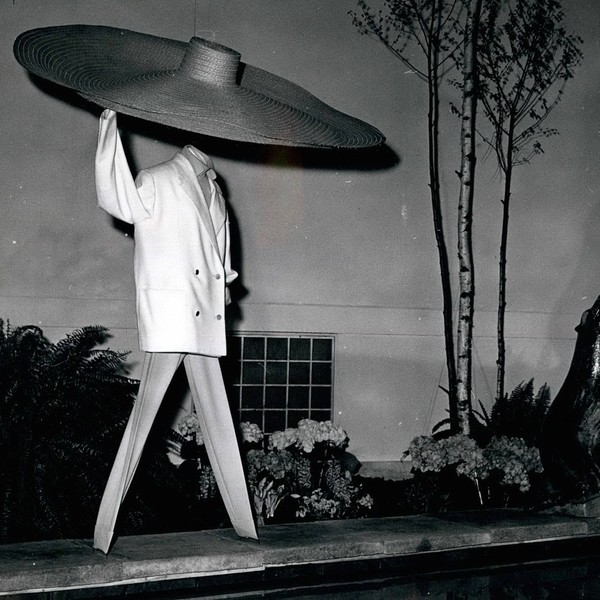

Vi Huynh wears a thrifted version of the High Sport pants;

Courtesy of Vi Huynh

Vi Huynh wears a thrifted version of the High Sport pants;

Courtesy of Vi Huynh

Solomon and Rufina both bought the pants and wrote about them on their Substacks. Both writers gave their honest opinions on everyone’s burning question: are they worth it? And, of course, where can one find a good dupe? Rufina’s review series, “The Scoop On The High Sport Dupe,” made the Substack rounds for its thorough list of dupes from Ann Mashburn, Donni, and Spanx to Banana Republic, Old Navy, and J.Crew. More chatter ensued.

Then, The Cut published a High Sport piece last month that laid bare the financial incentives for Substack writers recommending the High Sport pants with affiliate links. The public reception of the article drove the discourse around these pants towards suspicion. It reminded people of the importance of taking product recommendations with a grain of salt when someone stands to make a hefty commission.

High Sport skepticism has kindled on Substack—the same place where the fanfare began. This time, discourse around the pants are tinged with mixed feelings around the gray area of affiliate marketing and fashion writing. Kickbacks on the Kick Pant have soured the hype for many.

In her latest High Sport dupe post, Rufina ponders if we should aspire towards these pants in the first place: “Are they an unspoken application to an elite club, where the entry fee is a slim waist, a fat bank account, and a life elegantly soaring above the mundane irritations familiar to the rest of us?” Readers resonated with this perspective. The comment section contemplated the writers’ ability to make $135 per sale via affiliate links on a rave review. “For some people, these pants might still be their top pick, fitt ing their style and budget. But knowing about the commission thing bursts the bubble,” Rufina continues. Solomon reflects on how the High Sport hype has played out. “I have noticed a little more skepticism, almost like we can all suddenly breathe a sigh of relief and go…wait, aren’t these just thick, hot pants that have a cute length?”

Vi Huynh wears a thrifted version of the High Sport pants;

Courtesy of Vi Huynh

Rachel Solomon wears the High Sport Kick pants;

Courtesy of Rachel Solomon

Some have held a critical eye towards High Sport pants from the start. Em Seely Katz, news editor of Magasin and writer of Human Repeller, knows the nitty-gritty economics of luxury clothing production and marketing. “I know a pair of stretch pants should not cost nearly a grand without a 1000% or so markup,” Seely-Katz reveals.

When vintage seller Vi Huynh first saw the High Sport pants, the “egregious price point” stopped her from what would have been an immediate purchase otherwise. Huynh keeps up with niche fashion discourse and believes that High Sport’s brand strategy relies on the appeal of “quiet luxury” rather than a truly superior material product. “They don't need regular people buying their pants. They're saying: we're the Loro Piana of stretch pants,” she continues.

Despite the skepticism around price point and kickbacks, the appetite for High Sport dupes has not waned. Seely-Katz has been diligently researching mid-price-range dupes in response to the Magasin readership’s interest. For example, they say that Sézane's new gingham pants (around $200) are just as worthy of wear as the originals. Huynh maintains that the High Sport look is easy to find at thrift stores due to the popularity of ponte pants during the 90s and 2000s. Her advice? Focus on material—while rayon, polyester, and spandex blends are common, the better quality ones feel thick to the touch and retain shape when stretched.

However, High Sport diehards maintain that the dupes are incomparable to the original. Writer Jess Graves of The Love List reports that the material from Old Navy and Donni versions were “flimsy and thin,” a far cry from High Sport’s “thick Italian knit that holds you in.” Graves, who purchased the High Sports with her own money, wears the pants “so often the cost per wear is probably around a dollar at this point.”

Ruffina wears a dupe of the High Sport pants;

Courtesy of Rufina

Vi Huynh wears a thrifted version of the High Sport pants;

Courtesy of Vi Huynh

Unlike Instagram, Substack is still a relatively new space where the norms of affiliate marketing—and how consumers can expect to engage with it—are still taking shape. One can find a broad mix of fashion content, from personal essays and styling tips to shopping-driven posts heavy on affiliate links. Perhaps it is due to this broad spectrum of how and when writers participate in affiliate marketing that pinpointed skepticism towards High Sport pants in a way that may not have materialized on, say, Instagram.

Seely-Katz, who does use affiliate links on Human Repeller, emphasizes that they have built trust with their readers in terms of how they disclose commissions. “People who read my newsletter know that I emphatically don't go out of my way to center affiliate links, many of my posts having none at all [...] I am thoughtful about what products I endorse, no matter the price point,” they state. Graves echoes this sentiment. She views affiliate income as compensation for the work of content creation. In regards to her Substack, “my readers get that if I am publishing something without a paywall, affiliate links are a way to help me accrue some payment for that time spent. I don't let it sway my editorial decisions though,” Graves notes. Rufina does not use affiliate links but acknowledges that with the instability of the media landscape, “It's really tricky for me to say how writers should be making their money.” As a former advertising professional, her main concern was seeing High Sport purchase links posted without an affiliate disclaimer.

Ultimately, the story of High Sport reveals how Substack is becoming an increasingly robust ecosystem for launching status-y products that go viral within a subset of fashion consumers. Seely-Katz describes the phenomenon as a “self-fulfilling prophecy,” where people who buy such items are more likely to broadcast them in their publications, “creating an illusion that literally everyone is buying this stuff.”