This Glitzy Debut Novel Delves Into the Power of Charm as Currency

Marlowe Granados' Happy Hour is a modern day coming-of-age story.

"My mother always told me that to be a girl one must be especially clever." That is how Marlowe Granados opens her debut novel Happy Hour. It calls to mind "Girl", the short story by Jamaica Kincaid, which is one long sentence packed with instructions from a mother passed down to her daughter. "Wash the white clothes on Monday and put them on the stone heap; wash the color clothes on Tuesday and put them on the clothesline to dry; don't walk bare-head in the hot sun; cook pumpkin fritters in very hot sweet oil; soak your little cloths right after you take them off." The mother imparts practical tips, advice on making the most out of life, and several scoldings, all with the hope that it will help her daughter survive in a patriarchal society.

Though Isa's mother is no longer in her life for reasons we find out towards the end of the novel (don't worry—I won't spoil anything for you), we do learn that she holds one piece of maternal advice close to her heart: "In life, you must familiarize yourself with what is glamorous." And so she does.

The novel is set against the playful landscape of the summer of 2013 in New York City. Following a stint in London, Isa's adventures have brought her to Bed-Stuy, where she moves into a room with Gala, an old friend. Due to a lack of proper paperwork, the two 21-year-old women lack access to jobs that require proof of permanent residence, which means they have to hustle. Their random assortment of gigs includes selling clothes at a market stall, becoming members of a TV studio audience, convincing men to buy bottles at a club in the Meatpacking District, and modeling nude for an art class.

A side-effect that comes along with trying to figure out where your next meal will come from is stress, yet the sensation doesn't seep into the first part of the novel. The writing is conversational and lively. Isa confides in the readers, as if she's inviting us into the party herself. She passes quippy judgements on those around her and she's tuned into the fashionable excess of the people she finds herself shoulder-to-shoulder with at costume parties, gallery openings, and housewarmings. Isa appears to have a certain level of self-assurance; a lack of access to an endless flow of funds doesn't stop her from living life on her own terms and acquiring bits and pieces of glamour along the way. The money Isa and Gala earn from their time as studio audience members? "We only get $50 each, but collectively, that's at least one late-night cab home, a dozen oysters during happy hour, a small bottle of Tanqueray, and maybe one unlimited seven-day MetroCard."

*

When you're a young woman, whether or not you have money or other resources to exchange, society's preferred method of currency is your looks and your charm. In her essay, "AOC's Attractiveness Drives Us All Mad," sociologist and writer Tressie McMillan Cottom argues that a main reason why Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's critics attack her is because of her looks:

"I believe that in this worldview, which is the dominant one, beauty is seen as the only legitimate capital that women are allowed to possess. But beauty is supposed to serve power's interests." She goes on to write, "We also feel icky about pointing out that someone is attractive and that is a certain kind of power because powerful women make us squeamish. And beauty as power makes us deeply afraid for our own self-worth. As much as we want to believe that we are above 'looks,' we are all subject to them."

Recognizing power dynamics and feeling uncomfortable about them has become a common trope in contemporary fiction. In an essay for The New Yorker titled "Has Self-Awareness Gone Too Far in Fiction?," Katy Waldman states that "these self-conscious times have furnished us with a new fallacy. Call it the reflexivity trap. This is the implicit, and sometimes explicit, idea that professing awareness of a fault absolves you of that fault—that lip service equals resistance."

There's an underlying thread that connects the narrators of the novels that Waldman refers to in her piece. For various reasons, the top one being late capitalism, they feel guilty in their pursuit of pleasure. Isa feels no shame in her quest for a good time, à la Eve Babitz in Los Angeles during the late '70s. Referring to people she met during her time in England, Isa says, "I stayed friends with a few because of their casual regard for money;" when discussing her goals for the summer, she states that while it "is about branching out into a semblance of adulthood, it's also about fun. I take both seriously." She's not embarrassed to admit that after purchasing a yellow linen Escada dress, she "could only afford to eat canned soup for a week after purchasing it from a consignment store." Isa's financial precarity is inextricably tied to her affinity towards excess: "Anyone who prefers minimalism probably had everything else growing up...I love fur and everything else that was not meant for me, like caviar and champagne. Whenever I'm around luxury, I want to be so overindulged I get sick because of it." She's not afraid to use her looks to climb the ladder, to get where she wants to go.

*

The novel follows a structure similar to that of a fête. When an evening begins at happy hour, who knows where the night could take you? But what happens when you stay at a party a little too long; when you've had one too many spicy mezcal drinks? As the night progresses, party-goers typically begin to unravel, revealing their true selves. No one wants to be the last one standing, forced to gaze upon their vices in broad daylight.

But that's what begins to happen in Happy Hour; the lightness that encompasses the opening of the novel starts to dim. Granados does a masterful job at touching on race and class without hitting the reader over the head with overused tropes or stale language. The reader becomes aware of the messy dynamics between Isa, who is a woman of color, and Gala, who is white, through their interactions—it's never stated for the reader explicitly. During a heated moment in the novel, Isa says to Gala, "Don't forget...you're the one who has always been allowed to act out...it's a luxury you've been given. People always made me responsible for what you did." Isa grows more honest with the reader, admitting that she's "never been the right type of thin" and acknowledging that using beauty as a currency comes at a price. "The less time spent in public, the safer girls feel," says Isa. "That's not incidental." As the novel progresses, Isa's age begins to show as well. She sees personality traits as things she can acquire to make herself more interesting. She teases people for caring too much while sharing the same flaws. She is gnawed at by a feeling that she has something to prove; that she needs to earn her keep in order to continue moving in these upper-class social circles. The second half of the story is where Granados's sentences dazzle. Isa is more honest, with herself and the readers, and the prose becomes poetic and sharp.

*

Isa's mother looms large over the novel. The chapter's are titled as dates, making them read as journal entries. Isa keeps a journal herself and later in the novel, we learn that her mother did as well. When Isa comes across older women—semi-maternal figures—they help shape her views on the world. She meets Anabel, an artist with whom Isa immediately connects, and who shares advice like, "Never wait to be chosen to treat you right. I know it may not seem this way in art and literature, but we are not mere vessels for love and admiration," a modern version of a statement that could've been pulled directly from Mary Wollstencraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Women.

*

According to Sarah Sherymen, an English doctoral candidate at the University of Georgia, "feminist poetics is an attempt to escape from womanhood defined by men. My embrace of vanity is an attempt to escape from beauty defined by my beholder." Her interpretation of beauty isn't tied to how others, specifically men, see her and it has no relationship to morality. "My definition of beauty is simple: sensory pleasure...as the definition of the term beauty is not static, we can indulge in not being static in our approach to self." Isa shares a similar perspective. "It is funny that most people want money for the power. I want money so I can have beautiful things—surround myself with them." We see Isa go through several transformations throughout her summer in the city, trying on different personas, and figuring out who she wants to be as a 20-something woman. But throughout the many evolutions, there remains a common thread. "Perhaps it is not a coincidence that I write things into remembrance. I like to linger long enough to name pleasurable things and seek out more." Wherever her sense of adventure takes her next, she will continue to familiarize herself with the glamorous.

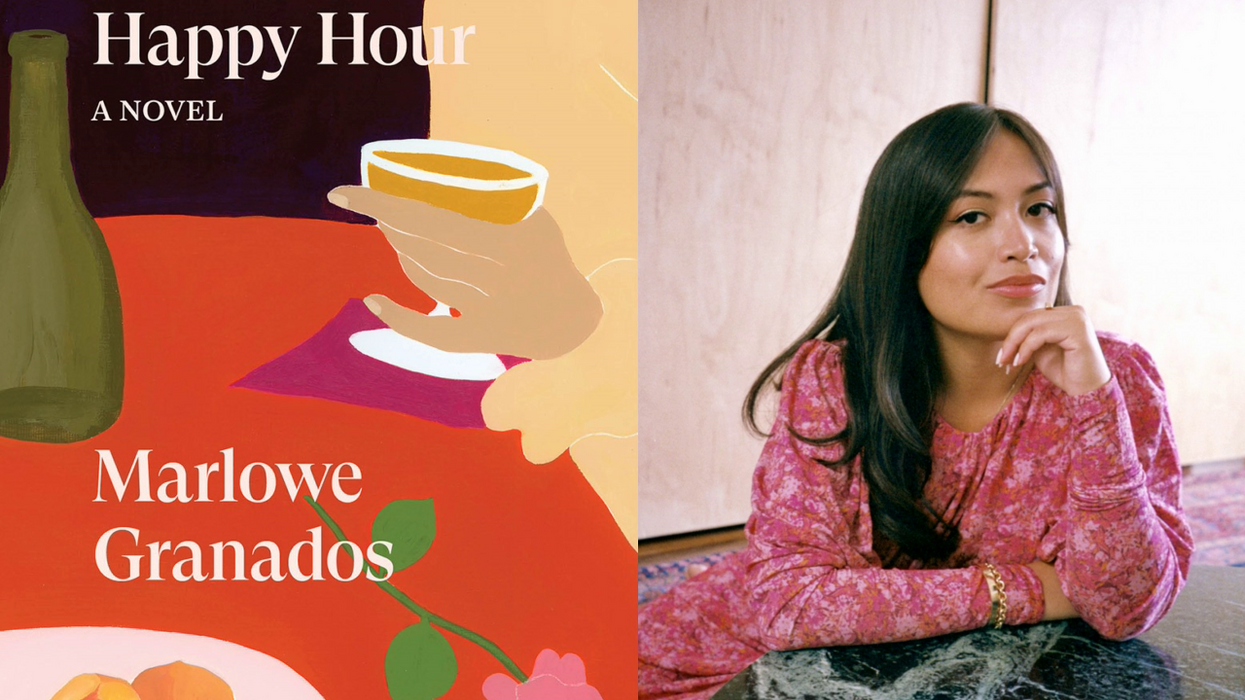

Top photo (left to right): Courtesy of Verso Books; Basia Wyszynski

Want more stories like this?

The Summer Read That Dissects Narcissism, Desire, & Love

Everything You Need for a Superior Reading Nook

13 Fall Books to Cozy Up With This Season