A Case For Doing Less

In an era of never-ending goals and burnout, what happens when you stop trying to improve yourself?

I was eight years old when I decided I was going to become a bestselling author. Around the age of eleven, I started weighing a career change to first female president. By the time I was fourteen, however, I had set my sights on a new goal entirely: founder and editor-in-chief of the world’s most prestigious arts and entertainment magazine.

Suffice it to say, I’ve always been ambitious. I rarely allow myself a moment to appreciate my accomplishments before I start berating myself for being behind on the next one. I often joke—as a writer, a filmmaker, and an attorney—that my profession is actually three careers in a trench coat. I count my steps, track my calories, and catalog every book I read or movie I watch. I start a new time- and labor-intensive hobby every two to five business months. (Please don’t ask me about my abandoned roller derby career, the number of unfinished knitting projects I have strewn about my apartment, or the YA romance manuscript in my sock drawer.)

For those of us who want to unhinge our jaw and swallow the world, sitting still is anathema. That doesn’t mean we don’t do it, of course; as an ADHD-haver, I can lose half a day staring vacantly at the wall while internally trying to wrestle my attention span into submission. But it does mean I feel terrible about it every time—so you can imagine the number it did on my psyche when, as 2025 progressed, I found myself increasingly unable to see through the fog of the next five minutes.

By any objective measure, 2025 sucked. Life got (even) more expensive; fascism in the United States went from theoretical to covert to in-your-face in the blink of an eye; ecological disasters like the L.A. fires ravaged communities across the country. For my part, I got laid off, spent months living at my parents’ house, and started what has since revealed itself to be the most demanding (though also, perhaps, the most rewarding) full-time job I’ve ever had. To my unspeakable frustration, as my new job monopolized increasingly more of my time and dedication, I found myself moving ever more slowly through each day. My limbs grew leaden, my head heavy, and daily tasks were getting harder and harder to bear. Even so, all I could think about were the projects I’d paused, the side hustles I’d allowed to fall by the wayside. No matter how hard it got to do the bare minimum, the feeling that I wasn’t doing enough gnawed at me.

Until I gave up on doing any of it.

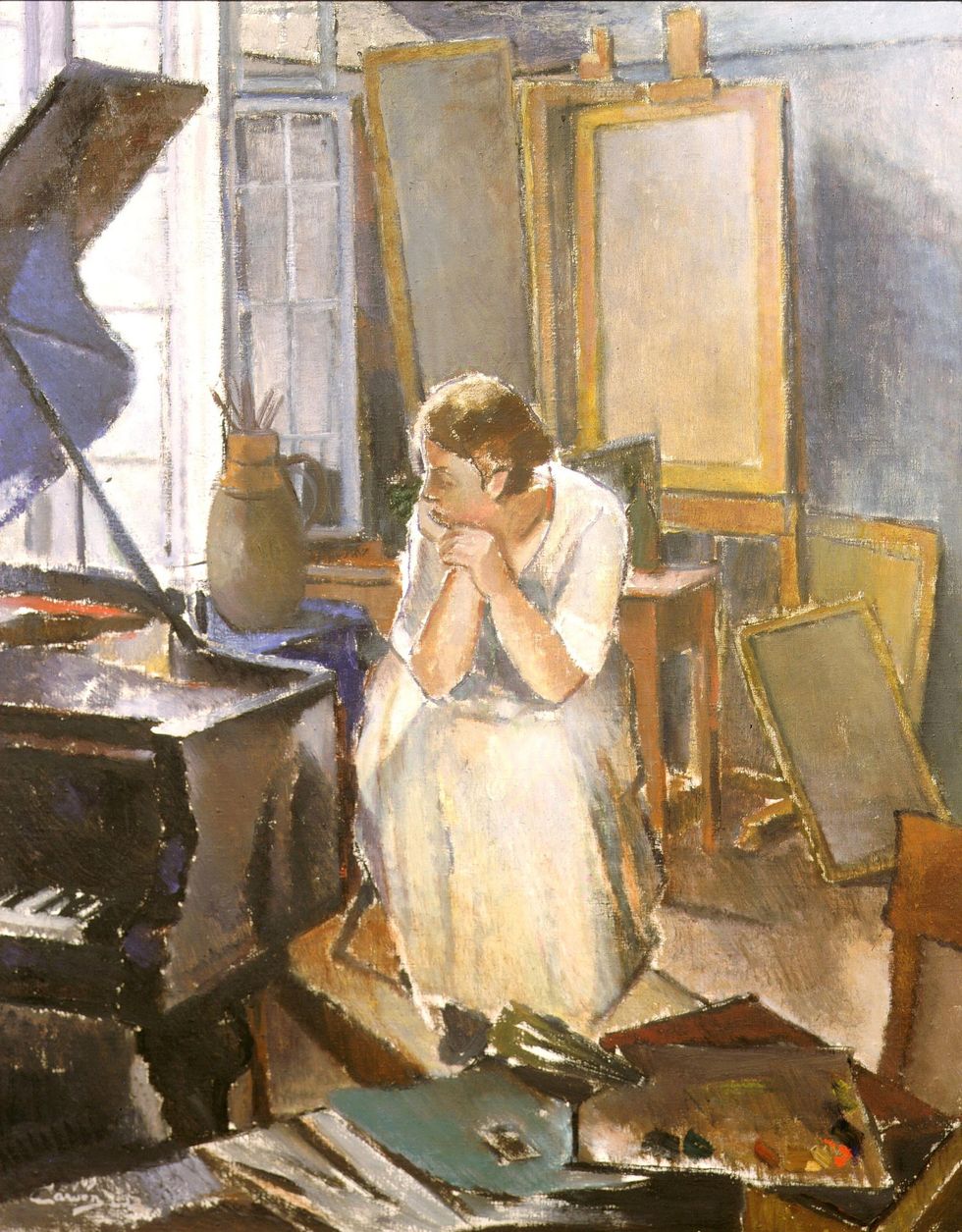

Alfredo Dagli Orti/Shutterstock

Whatever the reason is to blame for my recent hard left into Taoism, I was suddenly very sure of one truth above all else: nothing matters. We are mere specks in the eye of the universe, barely a blip in the cosmos—what difference does it make that I read 16 books last year instead of my usual 60? So what if I don’t read any in 2026?

Honestly? Probably nothing. “Think of all the times that you’ve tried to optimize and it hasn’t worked, or all the times you’ve obsessively planned for the future and it’s not gone that way, and you’ve actually been fine,” says Liz Folie, LMFT, a marriage and family therapist whose Los Angeles practice specializes in depression, anxiety, and addiction issues. Obsessive goal-setting and self-optimizing often go hand in hand with future-tripping—i.e., fixating on what-if scenarios to the point of anticipatory anxiety. But it’s easy to forget that the imaginary future playing out on the back of your eyelids isn’t a foregone conclusion. “The future is not real. The future is a thought form,” says Folie. And planning for the future can easily give way to ruminating. “Deciding to get lunch with someone on Saturday is planning. But anytime I’m losing my presence in this moment by thinking about what’s going to happen at lunch, what we’re going to talk about—anytime I tell myself I know what’s going to happen—then I’m losing my connection with the present moment," she says. Scripting out the future in your head doesn’t actually mean you know how things are going to unfold; it just pulls you out of the present.

Another side to the allure—and the danger—of future-tripping: projecting certainty onto an uncertain future can also be a way of distracting yourself from the discomfort of being alive. “Everyone has intrusive thoughts,” says Kyle Jacobson, Associate Clinical Social Worker, whose work focuses on OCD and anxiety disorders. “When people have an aversive relationship with their intrusive thoughts, sometimes there’s this rule of, ‘I can’t slow down or else I might actually have to deal with the stress.’” She notes that staying as busy as possible can be an avoidant tactic, because then you don’t have to deal with my anxiety or depression or with those obsessions that are coming up. “But that’s not the same as controlling those feelings—in fact, that’s not even possible,” she says. “For the most part, our thoughts and feelings are out of our control. How we respond to our thoughts and feelings is way more in our control. Being able to make that distinction and let go [of trying to control your feelings] can be really freeing.”

Alfredo Dagli Orti/Shutterstock

Even so, learning to let go of obsessive thoughts doesn’t affect the reality of living in a rapidly changing world. Rent and groceries have skyrocketed in cost, and Donald Trump is threatening to invade Greenland. In major U.S. cities, our friends and neighbors can’t leave the house without risking state abduction. The personal is, indeed, political: these things likely have tangible effects on our daily lives. “We’re collectively traumatized,” says Folie. “[COVID was] hugely isolating, and our social muscles atrophied, and we became hugely disregulated."

In the face of such existential anxieties, goal-setting is more than just a distraction: it can feel like the only way out of the endless tunnel of stress. “It’s definitely not uncommon that the more out of control things might feel, the more you’re going to try to control every little thing that you can— your anxiety, your sleep, how much you’re eating,” says Jacobson. “You can become hyperfocused on that as a way to avoid the external stressors that are so out of our control in reality.”

But that doesn’t actually translate to control over those external factors. In the end, when I try to plan or optimize my way out of current stress, I’m not actually gaining any sort of say in how the future unfolds. All I’m doing is robbing myself of the present. “Your anxiety lies to you and tells you that once you’ve accomplished this task then you’re going to be happy,” Folie explains. “But the mind then becomes addicted to finishing tasks, and you may notice that you’re never actually happy, you’re always just waiting for the next task to finish. You’re putting your happiness in the future rather than making the present moment your focus. It’s this false idea that in the future I’ll be fulfilled, but that means that right now I don’t see myself as fulfilled.”

Ultimately, none of this is going to matter in a thousand years. These days, if I find myself planning ahead or trying to sketch out the future, I change course and turn inward: Have I gone for a walk today? Have I had a glass of water lately? This is applicable to political anxieties, too—staying connected to the communities you belong to is the best way to know what those communities need. Plus, there’s a bonus to staying in the now: the stuff that’s actually beyond our control feels easier to handle. “Removing the goal-setting framework and practicing awareness of the present moment can lead to a much more regulated and resilient state,” says Folie. “Practicing gratitude and practicing mindfulness strengthen our prefrontal cortex and allow us to increase our psychological flexibility so that we can handle whatever life throws at us.” Jacobson agrees: “The more you let go of what you just genuinely can’t control, the less stress, the less anxiety and the more overall vitality you have in life.”

That applies to self-optimization, too. It’s tempting to fantasize about an ideal version of oneself that’s perfectly equipped to navigate the injustices of both our lives and the world. But that’s often because “we’re afraid that we’re not good enough, that we’re not whole already. But what if we’re good enough already and whole already simply by being alive?” Folie asks. If everything needs to be optimized in order for life to be worth living, “then that means that right now I don’t see myself as a whole person. What if you’re a whole person in the present moment?”

So, yeah, for 2026 I’m not worrying about achieving major accomplishments or evolving into the best version of myself. I’m just going to let myself live—100% goal-free.