Constance Wu is Adding Context to Her Story

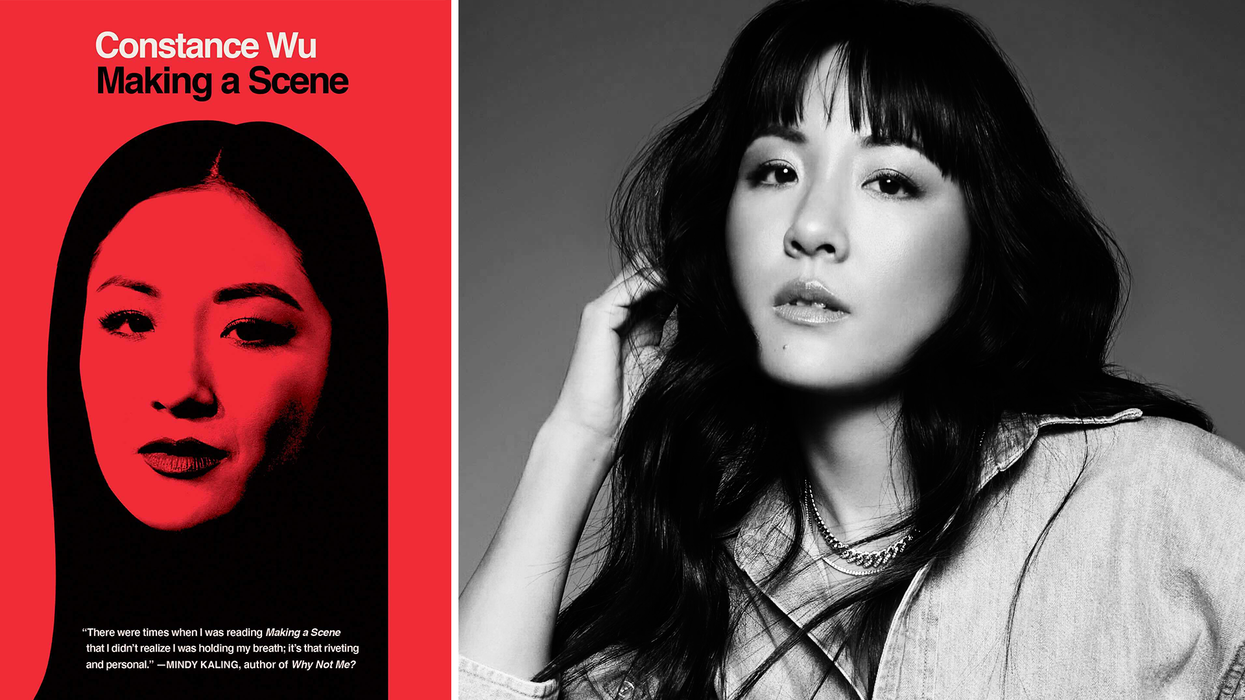

In her essay collection, "Making a Scene," Wu opens up about the moments that "shaped her humanity."

Much has been said about social media and how it has given celebrities an unprecedented amount of control over their image and self that is portrayed to the public. Traditional media used to play the role of intermediary but social media has allowed celebrities to cut out the middleman, giving individuals more power than ever to shape their own narrative. However, this new sense of control isn’t without its pitfalls. In his book “Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man,” mid-century media theorist Marshall McLuhan talks about how the medium is the message: aka the medium, or platform, influences how the message is perceived. The content can’t be separated from the medium it exists on. In the case of social media, more specifically Twitter, the medium doesn’t allow for much context. A majority of the platform consists of short bites, hot takes, and evoking reactionary and emotional responses.

In the spring of 2019, “Fresh Off the Boat,” a television sitcom that aired on ABC was up for renewal and most members of the cast and crew, including actress Constance Wu, were expecting a cancellation due to falling ratings. But the show was renewed and the acting projects that Wu had planned on pursuing—an Off Broadway film and a film—were no longer an option for her. Wu, in an emotional and impulsive state, sent off a series of tweets that were met with intense backlash. After seeking help through therapy and taking.a social media break, Wu picked up a project that she had begun writing in the wake of the 2016 presidential election: a book.

According to McLuhan, print is a slower, more deliberative, and demanding medium. It allows for more nuance and greater context. It is the domain of ideas. In “Making a Scene,” out on October 4th, Wu shares 18 essays about moments that “shaped her humanity.” Ahead, Wu shares why this is a different book than the one she initially set out to write, what it was like to write about her suicide attempt, and more.

I'm curious about the construction of the collection. What was the first essay you wrote when you started this project?

The very first essay I wrote is actually the first essay in the book, if you don't count the introduction: Lucky Bucks. It's funny because some people have been calling this book a memoir. I don't really think of it as such. I think of it as a collection of personal essays because I wrote each essay as the memories occurred to me, and some of them I wrote simultaneously. When I finished writing all of them, I ordered them according to themes in my life, not chronology. The process of writing it was less linear and more organic.

I noticed that it was written non-linearly. To me, the structure reflected a psychological function; it was a comment on the fallibility of memory, and also a way of circling difficult events. Would you agree with that?

Well, I never intended for it to be a memoir in the first place. When I first started writing it, I thought it was going to be a political activist book. I thought it was going to be idea driven. I thought it wasn't going to be about me at all. It was going to be about politics. And as I wrote, I didn't really like what I was writing, and I recognized that the parts I did feel connected to were the more personal, intimate stories that had nothing to do with politics. My first job working at Bread Bakery had nothing to do with my political views whatsoever, but it had a lot to do with who I am as a person.

I just wrote memories as they came to me whether it's baking bread, or being raped, or remembering my mother taking me to houses under construction. It's a collection of different moments in my life that were formative, and how I reflect on it now. Each essay is meant to be able to stand alone.

Towards the beginning of the collection you write about a teacher who accused you of plagiarism and how the accusation drove you away from writing. What brought you back to the craft?

The process of writing this book is what brought me back to writing. I started writing around the time of Trump's election. [It was a time] where I think the whole country, including myself, was trying to process and understand a lot. I was emotional and discombobulated that writing was a way for me to get these feelings out about what was happening in the political climate, and to work through it in a way that I could control. I can't control what's happening in Washington, but I can control what I put on the page.

And like I said before, it changed into a book that was not politically motivated. I think that's what naturally happens when you're writing about big feelings, whether it's about an election or about a breakup. You start to think about the things that made you have these feelings, like who you are in the context of these election results, or this breakup, or this experience. So the writing guided me, rather than me guiding the writing.

Did you share what you were writing about with the people you were writing about?

I did, yes, eventually when I was done with it. I wanted to be respectful and ask for permission. My sister knows about the sister [essay]. My parents, I had to get their permission too, and they had little thoughts and insights that were helpful to me as well.

I didn't share it with the teacher [who accused me of plagiarism]. I think she's passed away. The only people I probably didn't share it with were Rich and Cher, the bakery owners, because I don't really say anything bad about them, and because in that essay I say, for some reason, I'm shy and I'm embarrassed to go back to them because I'm afraid they won't remember me. So I didn't share that essay with them, but I hope they read it. I hope they know how much they meant to me and how much it meant to me that they taught me how to bake bread. But everybody else—all the guys I write about, all the ex-boyfriends—they know.

Oh, you went to your ex-boyfriends? What was that like?

It was fine. I'm on good terms with all my exes. I know that's strange, but I am. It was almost nice in a way, but they all gave me their blessings.

With your family, was there tension in that initial conversation when you brought the essays to them?

Yes, there were definitely nerves for both parties. With my sister, while it was difficult to approach the topic, once we talked about everything, it actually was really connective for us.

It meant a lot to me that she said to me, ha, it's so interesting to hear that you felt that way because I was missing you too. Hearing her say, too, was so moving to me because the whole time when I was in middle school, I thought she was abandoning me, that she didn't want to be my friend anymore. So to learn now as an adult that she missed me at the same time I was missing her and pretending not to miss her was really moving. It's actually brought us closer.

In the book, you also write about how once you reached a stable place in your career, the memory of your sexual assault came flooding back. Did any other memories come back once you felt more “secure?”

Definitely, other memories have come back. It was more so the fact that this memory came back and I didn't understand why it came back. That's why I had to investigate that, because if trauma is so bad that your mind blanks on it, then why remember it at all? I'm still sorting through that. But I think your mind lets you face things when you're ready to talk about them. Even with my recent tweets where I was talking about my suicide attempt, I could have been honest about that when it first happened, but I was so raw and wounded at that time that it would've been like hitting an open wound. You have to heal a bit first before you can process and help others.

That was three years ago, and I have found tools to work through it and heal a little bit, though it will always remain scary to me. I felt that it was important for me to talk about because the importance of helping people outweighed my fear of talking about it, at this point in my life.

I noticed there was a shift in the prose in the scene where you write about the suicide attempt. The sentences felt longer, there was a very strong propulsive energy throughout that whole section. What it was like to write that scene?

When I was writing that, I was writing it in a fever state. I was crying and typing away and I wasn't worrying about grammar or sentences. It was flowing out of me as if I was living the experience again. I think the prose came out that way because that was the feeling of the experience. It wasn't a measured, rational act. It was something that was born of very high emotions, uncertainty, and fear of my own impulsivity.

I write about falls three times in the book, once in the beginning, once in the middle, and once at the end. At the beginning I write about skydiving with my ex-boyfriend. In the middle I talk about jumping off a cliff into a pool in Hawaii. Then at the end I write about almost jumping off a building and how I am so aware that I have this natural impulsivity. That was what was so scary to me, that it could have almost happened. That's why I had to be pulled over the balcony. That's why I had to be taken to the hospital and be placed under observation. Because it wasn't me in my most rational mindset. So I tried to write about it in the way it felt at the time.