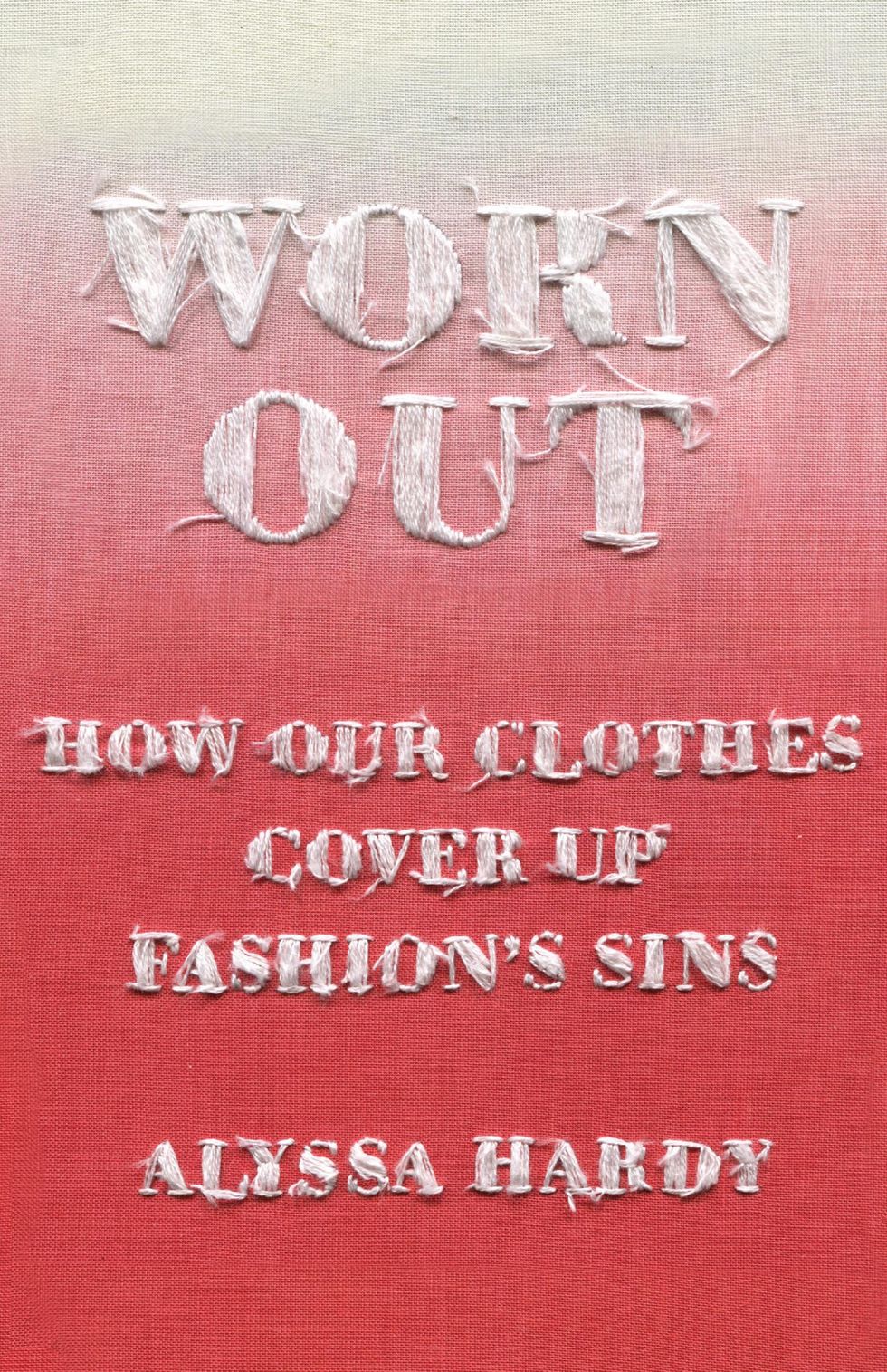

Uncomplicating Sustainability and Ethics In The Fashion Industry

Fashion journalist Alyssa Hardy explores how we can take acton and where that leads us next.

If there’s one hot-button topic dominating the fashion industry today, it’s the question of sustainability. There’s no question that the creation of clothing — from high fashion to high street — leads to a lot of waste, with no one magical bullet solution in sight.

But on top of the sustainability quandary, there’s also a load of ethical problems, too: We shouldn’t just be asking what our clothes are made of, but who made them and how those people are treated. That’s the question fashion journalist Alyssa Hardy tackles in her new book, Worn Out: How Our Clothes Cover Up Fashion’s Sins.

Hardy has built her career on covering these issues, first at Teen Vogue and then at InStyle before branching out as a freelancer. She was writing for Teen Vogue when the brand was at the peak of its march into politically-charged storytelling, and saw an opportunity to report on fashion outside of what celebrities were wearing. “I started learning a little bit more about some of the brands that we had been writing about and wanted to show the other side of these brands that we were covering,” she explains.

As her stories were aggregated across other Condé Nast brands, Hardy began to consider how she might dive in deeper. After being connected with an agent through an editor friend, she sold her proposal to The New Press, the perfect home for her ambitious project. “I obviously don't have the experiences of so many of the people that I write about, so I wanted to have an editor that had the experience in looking at issues like this on a global scale,” Hardy says.

“The thing about exploitation in fashion, in my opinion, is that it's not something that is often approached with a global lens in the way that it should be. The New Press is a very small publisher, but they have a very wide social justice lens, so I really was happy with going with them, because I knew that they would look critically at everything that I was writing, and also check me, too, as I was going through these issues, because they're so complicated.”

With Worn Out, Hardy admirably tackles the tangled-up web of ethical issues at the core of the fashion industry. She seamlessly weaves in her own stories of working in fashion media alongside interviews with garment workers from across the globe, giving the issue an important personal tone. The book is also incredibly approachable, making it the perfect starting point for anyone looking to get an overview of the human cost of disposable fashion.

Here, Hardy discusses how she put Worn Out together, why she doesn’t want consumers to feel shame and what we can do to fix this very broken system. (And, of course, there’s plenty more solutions offered up in Worn Out, available September 27!)

Who do you think your audience is for Worn Out?

For me, the audience is younger people who are gaining a little more interest in it. Working at Teen Vogue, the young audience was important to me, but it became really important to me once I saw the feedback that they were giving to our stories, like ‘We're not dumb, we know what's going on, but at the same time, you can't expect me to understand these really complicated issues. I just want a shirt!’ But I think that goes for older people too; we can't expect everybody to be experts in this stuff. Consumers shouldn't have to be a fashion supply chain knowledgeable person in order to buy an ethical shirt. Like, that's ridiculous.

In writing the book, I wanted to do something a little bit more narrative, because that's how I like to read. I love complex books about social issues, for sure, but I feel like there's so many of those in the fashion space that I was trying to get somebody to have something that maybe it would be a starter book for them. Then they could, as they get more interested, start to read some of the really incredible books that are out there.

What's the reading list after someone finishes your book?

Definitely Aja Barber’s book, Consumed, then Elizabeth Klein's books; she's very, very knowledgeable on this topic, she's doing the FABRIC ACT, she's been doing this for a long time. And then Fashionopolis by Dana Thomas.

I really appreciated your personal perspective — ‘I used to shop at Forever 21 all the time, this is what it looks like for fashion editors, this is what all of this looks like on the inside.’ Why was that perspective important to you to include?

Throughout my career as a fashion editor, I started to feel really weird about how the industry is structured and how much attention goes on to our side of things — and it is glamorous, and it is cool, so I understand why. But I started to feel a little bit like an accomplice within all of this. Telling that side of it was trying to take accountability for my piece in it and trying to show how much the media does obviously shape the narratives around fashion, and despite the fact that we all know that sweatshops exist and landfills in Ghana are filled with clothes with tags, the lead story is always still: ‘Hey, look at this really great shirt that's $3.’

People are doing their jobs, I was doing my job when I did that, but I also think that there is a piece that I need to take responsibility for within that, especially if I want to call myself a journalist. I have had so many jobs where I've had to take down stories, or I've gotten in trouble for saying things about a brand, and I just don't think that that's right. But fashion journalism is so unique.

I am noticing more and more on social media that these conversations that come up about shopping ethically, which makes people really defensive. But I felt like you tackled that really well and balanced that really well: ‘This $5 t-shirt comes at a cost, but there are communities who need affordable clothing.’ It's such a delicate tightrope to walk; how were you able to balance those narratives?

All of these things can be true. In terms of price, I approach it in a couple of different ways. Aja Barber, she's done some research on this, and it's not low income communities that are upholding fast fashion, it's middle income. That is also part of all of this conversation is that the premise is not exactly correct. But I understand as someone who didn't have very much money growing up, how I thought, ‘I have a school dance, nobody can afford anything other than Forever 21.’ I don't think we do the movement any service by pretending that part doesn't exist, and that people aren't going to do that.

I think the way to combat that is to, one, recognize that there's power outside of just consuming crap. Yea, you can do things with your dollar, but there's other ways to push this forward by simply talking about it. The whole point for me is to empower consumers to see that these brands do not give a shit about you, they just want your money, so they're not trying to provide some democratic access to clothing because they want to help poor people. If they wanted to help poor people, they would pay the people in their supply chain. It's the same with diversity and stuff like that in campaigns for fashion brands: it has nothing to do with actually caring about that. It has everything to do with marketing. People understanding that that's the case is can be so much more powerful than just simply telling people to stop shopping — which is important!

I hope the book addresses this in a way that feels like people can engage with it without feeling shamed. Because that’s the other part: shame is obviously such a powerful thing, but when you feel even the slightest bit of guilt or shame toward something that you're participating in, obviously, you're going to get defensive. I don't want people to feel shamed for that, because, again, at the end of the day, it's these companies, it’s the brands.

You talk a lot about fast fashion brands, but you're also very clear that these problems are not limited to fast fashion; high fashion brands do the same stuff.

I have a whole chapter about it, but handwork is a mess. It is a mess within the supply chain, and it's really upsetting when you think about it, but again, for me, it comes down to transparency and being able to say, ‘We know what this factory is.’ That's step one. But if you can't even get to step one, how can I trust you? And that's pretty much every luxury brand. It's just one of those things where, unless they're made to, they're not going to do it.

Who are you hoping reads the book, and what do you hope that they take away from it?

I love the idea of a young person who likes clothes picking this up and being like, ‘I'm aware of some sort of issues that might be surrounding my clothes,’ and they're going to get a bigger picture and realize that, from an action perspective, it's not just about consumption, especially now. There are bills and policies and unions that you can support and money that you can put towards things, and there are other things that you can do — even just tweeting about it.

Pretty Little Thing — they have so many problems, however, they did start doing actual audits on their factories, because people were really loud about it on social media. Whether those audits are actually doing anything, that's another story, but the pressure is valuable.