Danielle Prescod Takes on the Fashion Industry in Her New Memoir

The fashion editor talks childhood, the limits of social media in addressing diversity, and how whiteness in fashion shouldn’t be the default.

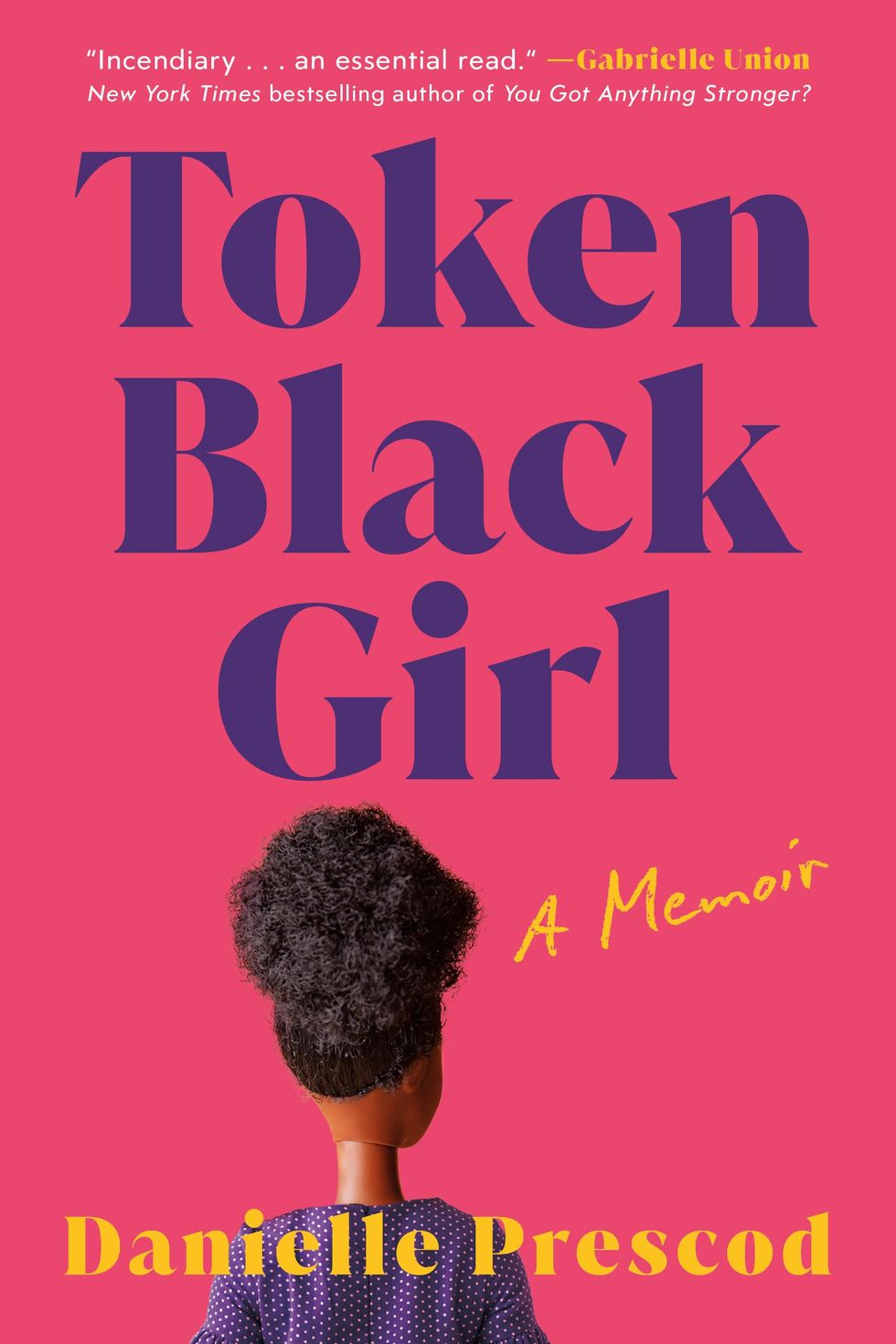

The cover of Danielle Prescod’s memoir, Token Black Girl, is a Black Barbie, hair in an afro puff, her body positioned away from viewers. It’s an apt image for Prescod’s personal journey — the accomplished fashion editor recently left her position as Style Director at BET.com and founded 2BG Consulting, with Chrissy Rutherford, the former Harper’s Bazaar Special Projects Director.

Prescod’s consulting company was a result of 15 years of working in the fashion industry and seeing the ways that whiteness was almost always centered, which is detailed in her memoir. But Token Black Girl isn’t just a fashion memoir or a manifesto about racism — it’s also a specific look at the kind of society that Black girls live in. The book also offers a portrait of a woman grappling with the physical and emotional consequences of being raised in a world where whiteness was seen as more desirable, more acceptable. Prescod takes an unflinching look at how the fashion industry has, and continues to, upholds whiteness, but also offers a guide to how things can improve.

You’ve been in the fashion industry for more than 15 years, working for publications like InStyle and Elle, along with BET.com. Why was now a good time for this book?

“I had wanted to write a book since 2018. I first started to write a fiction book, which I did, but it was really bad. All of my writing has been journalism - I interview people for features. I report on things, and I write personal narratives. It was difficult for me to write fiction, and I was also trying to do it while I had a full-time job. In January of 2020, I took myself on a vacation to Ireland and said to myself, ‘You have to figure out what this is.’ So I started writing what I knew and a lot of it was personal experiences. Ultimately, I was trying to figure out a road map of how I got to some of my deeper self-esteem issues. I had been in therapy for years and one thing that was always coming up in therapy was ‘You need self-love, you need to practice self-love.’ I thought to myself, ‘I obviously love myself — this is so dumb. But wait a minute, I think I only love myself if certain things are so perfectly working and aligned. So I was like ‘Where did that come from?’ So I started trying to unpack all of that.”

What was the most challenging part of writing the book?

“It was hard to convince myself that I had a valuable story. That’s because, in a lot of ways, I occupy a very privileged identity and I also occupy a very marginalized identity. I felt that in many traditional ways that I wasn’t necessarily struggling. I have two parents who love me, we’ve always had a home, and we’ve always had material things. But I was also like, ‘No, there’s obviously some real traumatic things that happened to you because you’re in those spaces and that’s valuable too. I had to convince myself that I don’t need to have these extreme circumstances of poverty or abuse or physical limitations or trauma to realize that my story also has value.”

Let’s talk about your childhood. You grew up in predominantly white spaces, absorbing media that shaped the way you saw yourself and other Black people, and you didn’t necessarily embrace your Black identity. What would you tell a younger self now?

“I think if my younger self had experiences where I was interacting with media that more positively depicted Blackness then I would have had an easier time. Of course, [Black media] was available, but it wasn’t necessarily what my direct community was celebrating. So I knew it existed, but I also knew that I was preconditioned to prefer the things that reflected whiteness. That’s why we need a lot of people to interact with all kinds of different media so we’re not just falling into this scenario where some stories are always viewed as something ‘other’ and whiteness is viewed as something neutral.”

You were very honest in the ways that you supported the fatphobic and anti-Black views in the fashion industry, sometimes directly and indirectly by not speaking up. Do you have regrets or do you chalk it up to part of being in the business?

“I think a lot of editors who were working in the late aughts have a ton of regrets about stuff that they published and did. So of course, there are things that I regret, but at the end of the day I was great at my job and if my job was then inadvertently to be a support system for white supremacy — that’s what the problem is. The problem is asking employees to do that. I didn’t invent this way of being, but I submitted myself to it.”

After leaving a publication like InStyle for BET.com, you faced some new challenges like limited access to talent and the unenthusiastic industry perception of Black media. But what were some of the advantages of working in a Black publication?

“I didn’t feel ostracized. My expectation based on my childhood was that I wasn’t Black enough. The kind of Black I am is kind of invalidated, but everyone that I worked with was like, ‘You’re just quirky and funny.’ It just created a safer space and it ended up making our work more collaborative because we were all invested in the same mission, which is to positively represent Blackness in the media so that allowed us to be able to do that in many different ways. I was the style director in charge of overseeing fashion, beauty, and lifestyle content and so I got to feature Black chefs and yogis — all these sorts of identities that might have existed when I worked at Instyle or Elle, but we were always defaulting to a white person.”

Did you fear backlash from publications or editors named in the book?

“I feel like I told the truth and I also didn’t say anything that other people didn’t witness. It’s not like any of this stuff was done in secret. People should be prepared to answer for the things that they were complicit in, in the same way that I have to answer for the things that I was complicit in. I also think we can change, improve, and get better.”

What changes do you want to see in the fashion industry regarding diversity and inclusion?

“What I really think needs to happen is admitting that on an institutional level, these are what problems we have. I think that for-profit brands have figured out how to colonize the language of acceptance and the language of inclusion, but it’s not true. For example, why is it that we can only look at clothes on teenage girls? That doesn’t make sense. What happens when you get over 40? Why aren’t we seeing all kinds of women wearing these things?”

We’re now in the age where so many of us are getting our fashion cues from Instagram and TikTok. Does social media still perpetuate harmful beauty standards or has it given us a level playing field?

“The playing field is certainly not level, but it does allow for a more democratic landscape. Algorithms are still biased no matter what because they are created by humans and humans have a bias and largely they’re created by white men. There is certainly a diversity problem within Big Tech that I think is slowly being addressed but not fast enough. I think that there are opportunities for people who look different that they could not have maybe 10-15 years ago, but I don’t think that social media necessarily fixes these issues.”

Is there a place in traditional fashion media for Black women, or do you think we’re better off creating our own publications and platforms?

“The thing about creating your own publication and platform is that building something from the ground up is so difficult. You really have to have an incredible amount of energy and fortitude to be able to do that. Frankly, I don’t think there’s a reason why we should not be able to participate in fashion media because if you’re saying that fashion is for women or for people, then why can’t we participate?”

What’s the end goal of 2BG Consulting after working with a company?

“The end goal is to let people operate in a more informed way. For example, what I wrote in my book is that a lot of what white supremacy does is put a chokehold over everything and you don’t even realize that you’re defaulting to whiteness. We want to loosen that up and have people think about things differently.

The problem with fashion, in general, is that we’re all pretty good storytellers, and we know that imagery can be powerful. When Chrissy and I consult with brands, we’re really trying to help them understand that they do not need to default to whiteness. We’re also not just trying to go for the appearance of diversity because then you’re still looking at people as objects. We want to help companies think about inclusion on all levels early so it’s not done retroactively, but done proactively.”