Inside Coachella’s Audacious, Underappreciated Art

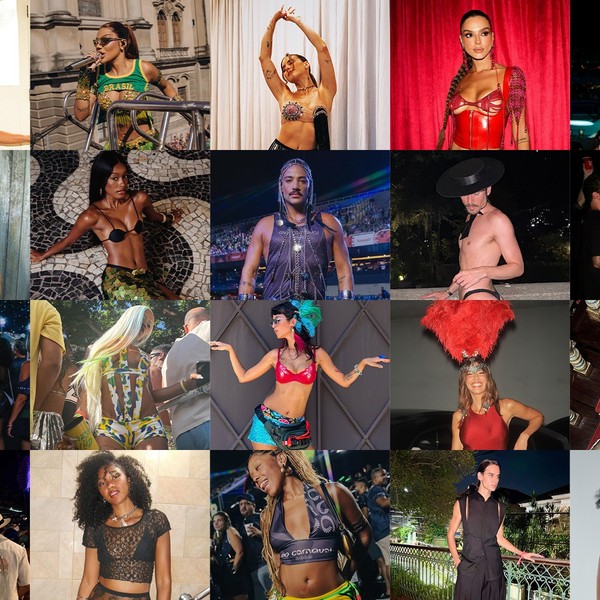

They may be great for the grid, but the colossal installations towering over the festival are far more than influencer bait.

It’s Friday, I’m at Coachella for the first time in my life, and because I’m a 35-year-old millennial whose music tastes haven’t evolved since the heyday of indie sleaze, I don’t recognize anyone outside the headliners on today’s lineup. That doesn’t bother me, though, because I’m not here for the music. It’s the colossal, glowing, immersive art installations that have lured me into the desert.

Coachella’s official name is “Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival,” but the latter half of the moniker rarely gets mentioned. I’m not sure why we don’t discuss the art much, though, because the aesthetics have been essential to building the festival’s fame. The bohemian spirit captured through every Instagram post is only possible because of the art installations that make for a spectacular photo opp, such as Spectra, the colorful, seven-story glass tower by NEWSUBSTANCE, which casts rainbows onto the polo fields when sunshine refracts through its colorful panes.

In the beginning, a much scrappier Coachella would loan pieces from Burning Man, which favors kinetic sculptures that glow at night and occasionally emit smoke or fire. Though Coachella prefers to keep pyrotechnics on stage, the festival embraced the funky folk art that came from their anarchist counterparts. In 2008, for instance, the festival used Mike Ross’s Big Rig Jig, a serpentine dance of truck cabs, as a shade structure. While I never saw the famous Burning Man piece in Black Rock Desert—that’s not my scene—I’ve snapped photographs of it in Las Vegas, its current home.

James Florio

James Florio

As Coachella grew, however, the festival began commissioning its own pieces. In 2016, the posters began including the artists’ names, putting them on equal footing with the bands. Under the direction of art director Paul Clemente, we’ve seen famed designer Jiminez Lai deliver a jumble of cartoon blocks with The Tower of Twelve Stories, United States Architect and Design Fellow Olalekan Jeyifous build an unreachable city atop an elephantine creature with Crown Ether, and numerous mechanical sculptures by Poetic Kinetics, including Escape Velocity, the roaming astronaut who floated through the 2014 festival flashing peace signs and thumbs up to starry-eyed guests.

The art pieces are getting bigger in concept, scale, and budget. If I still associated Coachella with a counterculture movement, as I once did when I was a college student reading the blog Hipster Runoff religiously, I’d roll my eyes at these oversized artworks that primarily function as influencers' props. But now, in the era where Coachella has become the most mainstream music festival in the world, I wouldn’t expect anything less audacious. And, let’s be honest, the photos are a great addition to the grid.

I was happy to discover that, when the festival wraps, many of the sculptures are woven into the landscape of the greater Palm Springs area. While I drove around the neighboring towns of La Quinta, Indio, and Cathedral City, I kept catching sights of Coachella’s repurposed public art, like Don Kennell’s 14-foot-tall Roadrunner, Edoardo Tresoldi wire mesh beaux-arts building Etherea, and Andrew Kovacs of Office Kovacs’s Colossal Cacti.

James Florio

James Florio

When I arrived at my first Coachella, instead of running to the barricades to stake out a front-row spot for Lana Del Rey, I started my day beelining to the top of Spectra to survey the crowd—dense and sold-out in week one, despite the complaints that this year’s lineup was weak—in a violet tone. I then came down to survey Robert Bose’s Balloon Chain, the long tether of latex that I had seen floating over the festival for more than a decade. The high winds lift the balloons more than half a mile into the air, putting them into the Federal Aviation Administration’s territory. What I hadn’t known was that I could actually grab onto the end of the cable, spiritually—and physically—connecting me to whoever was holding the other end of the 1,500-foot-long chain. Though the force of the wind nearly swept me into the sky, with the help of a staff member, we acted as anchors and became another link in the chain.

Once I experienced the reliable favorites, I headed over to the new, temporary art installations. For the past 10 years, Public Art Company, an agency helmed by curator Raffi Lehrer, has brought Clemente’s dreams to life. While the musical lineup may have left something to be desired, Lehrer outdid himself by pulling together a trio of monumental, technologically advanced, and sustainably fabricated installations. I let the festival’s music serve as the soundtrack for taking in Morag Myerscough’s kaleidoscopic playground, Nebbia’s brutalist tower, and HANNAH’s deconstructed house.

Myerscough is an art world headliner, and Dancing in the Sky’s performance did not disappoint. The Memphis-style dancefloor, color-blocked in summery hues and topped in kinetic spires, brought instant joy as I felt the vibrations from L'Impératrice’s groovy baseline, which emanated from the Outdoor Theater many yards away. Its many weathervanes, made of tessellations of triangles, circles, and ovals, twirled in the wind alongside the cowboy boot-stomping influencers.

James Florio

James Florio

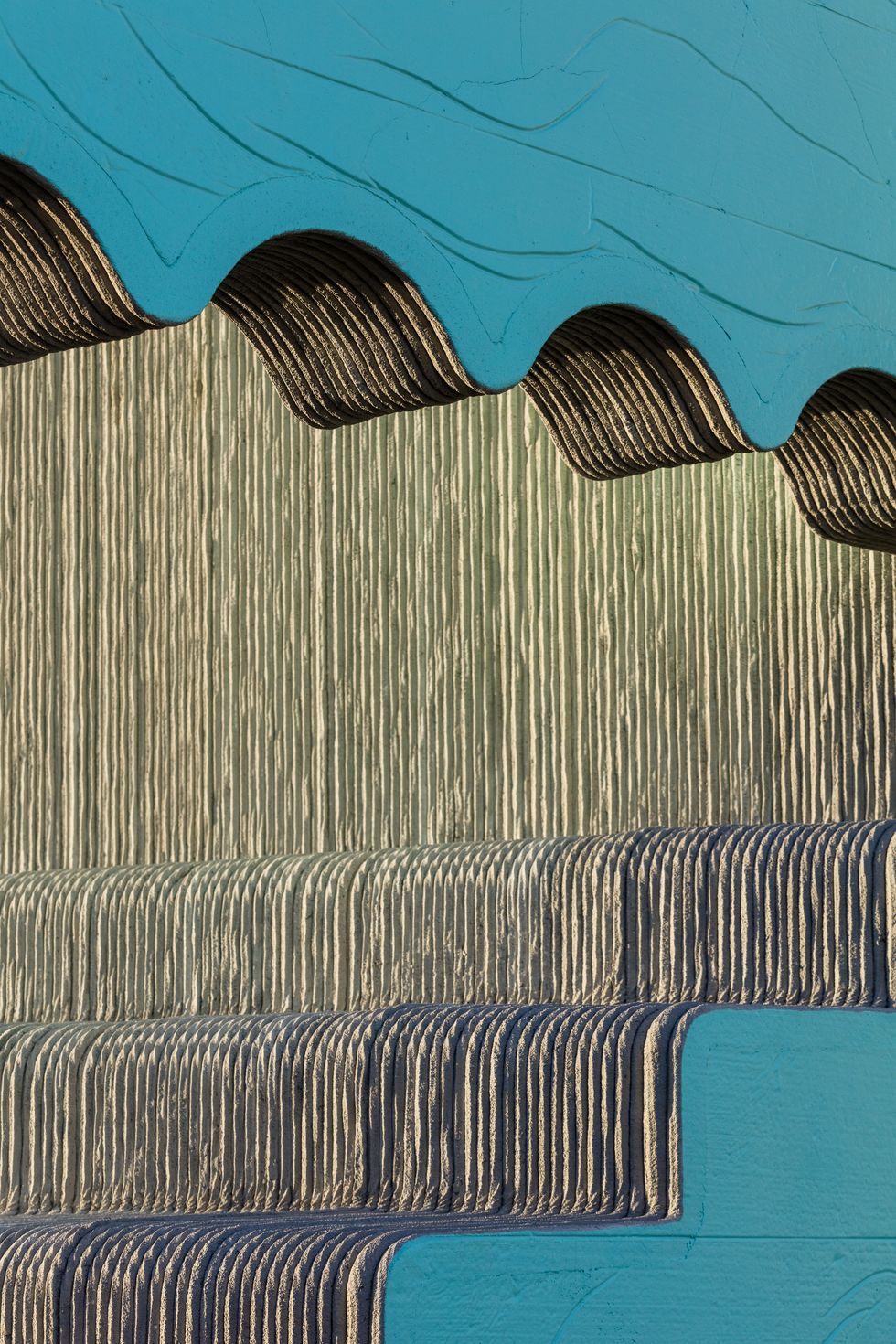

When it was time to relax, I sat in the cradle of oversized, 3D-printed concrete armchairs that were part of HANNAH’s Monarchs: A House in Six Parts. This was the most peaceful place I could find on the festival grounds. I stared up into the towering, parametric structures, which reminded me of the feathers on a shuttlecock, as sounds from the festival blurred together. In the daytime, when the speakers were still set to a reasonable volume, I couldn’t make out the lyrics from Sabrina Carpenter on the Coachella Stage or hear much more than the spooky beat pulsing from Eartheater in the adjacent Sonora tent. As the sun went down, LED rings lit up Monarch’s plywood blades, and it glowed in cyberpunk shades of orange, pink, and purple.

During the daytime, Nebbia’s Babylon had confused me. The gray tower made up of elongated semi-circles felt like a drab addition to the landscape. People tried climbing the sculpture by hopping onto its lowest blocks, coated in fragile plant-based cellulose insulation that read as fuzzy concrete, but security guards would force them down or chase them off. At night, however, I became a Babylon stan. The tower lit up in purple, and inside, projection maps of lava flows and galactic explosions lit up the church-like interior. It became a sacred space for mourning as Lil Uzi Vert, now performing on the main stage with the volume cranked up, reminded me that all their friends were dead.

In the art world, “immersive” has become an empty buzzword for describing a work that is simply large-scale. A truly immersive work engages all five senses, and the Coachella art program tries its best to deliver. In addition to building an interactive spectacle that transitions from day to night, Dancing in the Sky, Monarchs, and Babylon rely on the festival’s smells, tastes, and sounds to round out the experience. My memory of these pieces will forever be associated with cacophonous fragments from Young Miko, The Beths, and Chappell Roan, acts that previously had no significance to me.

Next year, if Taylor Swift finally headlines, I won’t be watching from the crowd, but from the cradle of flower buds on a kinetic cactus.