Who Gets To Be Chinese Now?

Growing up Chinese in America meant learning how to shrink myself. Now, my culture has become an aesthetic.

The first time I was made aware of my Chineseness, I was in second grade, standing in line for the school bus. An older girl named Sam had taken an interest in me, placing me under her protection like a pet. One afternoon, she held up her hand next to my face, then traced the tip of my nose with her pointer finger. “Your face…it’s so flat,” she marveled. “How come?”

I didn’t know the answer, so I shrugged. She smiled at me. “You’re like a doll,” she said, and I felt something shift inside me.

That night at the dinner table, I stared at the bowl of rice my mother placed in front of me. “妈妈, why is my face flat?” I asked her. She laughed. “It’s not flat,” she replied in Mandarin. “It’s Chinese.”

I began to resent my Chineseness. I disliked that it led to embarrassment, like when the teacher would mispronounce my Chinese name, Feier Xue, on the first day of school each year. “Fee-ray…Zoo?” My classmates would glance at each other and snicker. Why would someone have such a strange-sounding name?

As an adult, I know that denying my Chineseness would be denying myself. It’s written on my face. In the curve of my eyes, the bridge of my nose. It’s in my memories: bleary-eyed Saturday mornings at Chinese school; steaming bowls of 稀饭, or congee, with 榨菜, my favorite spicy pickled vegetable, for breakfast; peeling the taut skin off a longyan fruit with my teeth at my grandmother’s home in Shanghai, the sweet flesh breaking open against my tongue; my mother’s red bean soup, served as dessert. “It’s good for your skin, Fei Fei,” she would say.

My Chineseness is not something I can take off, like a winter coat when the weather gets warm. It’s in my bones.

Then, last week, I came across a video titled “How to Be a Chinese Baddie.” The woman was not Chinese, though she spoke with the confidence of someone explaining something self-evident. According to her, being Chinese could be approximated through drinking warm water in the morning and house slippers worn indoors. Soon after, another video surfaced. “You met me at a very Chinese time in my life,” an influencer wrote, stirring red dates and goji berries into a cup of tea she described as TCM. She wasn’t Chinese either.

Faith Xue

Lately, “Chinese” has become a kind of shorthand. It stands in for discipline, ancient remedies, slow living, and self-optimization; an aesthetic assembled from bone broths, herbal TCM teas, acupuncture, and gua sha. In the Western imagination, Chinese culture has reappeared as a lifestyle moodboard, stripped of its context and scaled neatly for social media. What’s being celebrated isn’t the culture itself, but a yassified version of it optimized for easy adoption.

In theory, this could be considered progress. It's better than overt racism.

But there is something strange about watching the culture you grew up with, once mocked, reappear as an aspirational social media trend. Except it isn’t the culture itself, but some sanitized, dumbed-down version of it, as if an entire civilization could be reduced to a 10-second video clip, taught by someone who doesn’t speak the language and probably doesn’t know any Chinese people.

“It gives everyone permission to cherry-pick whatever parts of our culture that serves them while discarding the context,” says Sable Yong, a beauty writer and author of Die Hot With A Vengeance: Essays On Vanity. “The commodification is what feels icky to me.”

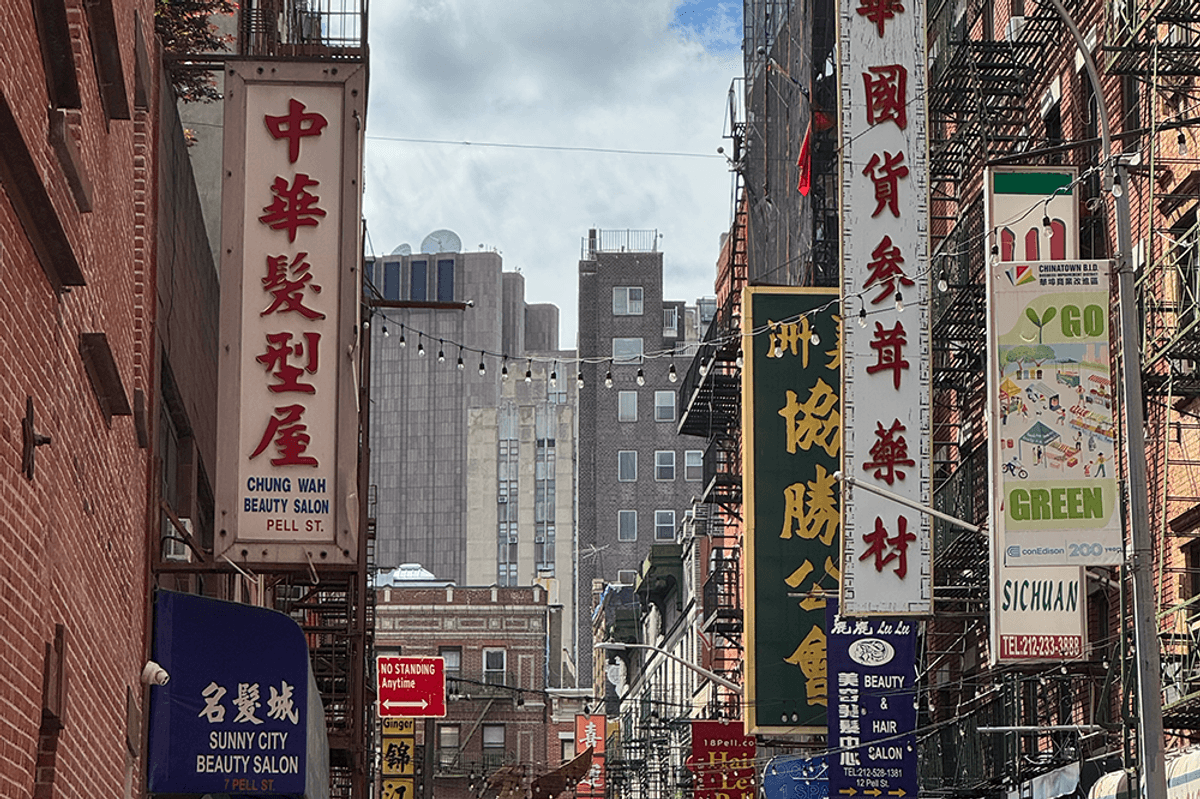

Arabelle Sicardi, writer and author of House Of Beauty: Lessons From The Image Industry, notes how the same people who were "lunchbox bullies are getting obsessed with Chinese stuff and [hunting for] for $20 blowouts in Chinatown now. Somehow, it feels racist, even when it’s complimentary.”

What’s striking about the trend isn’t that people are merely interested in Chinese culture, but that they want to be identified as part of it. I can’t help but wonder if the same people proudly declaring themselves “Chinese” now would still be doing the same in 2020, when Chinese people were targeted in hate crimes around the world, fearing for their lives. Or the decades before that, when when "Made in China" automatically something was cheap, and Chinese accents were ridiculed, our faces erased from films and television. Back then, our food and broths and herbs were deemed strange and subpar; our habits, like removing our shoes in the house, mocked by Western society. Where were the people calling themselves Chinese then?

Faith Xue

Because back then, I would have gladly traded my last name for theirs. As a child, I wanted to be loved by the world, and the world taught me that in order to achieve this, I needed to be more like Sam, with her silky hair and freckles and eyes like my favorite blue marble; with parents who fed her sticky-sweet syrupy medicine when she was sick, not gnarled, bitter roots grounded up by their acupuncturist like mine. For a long time, I absorbed the lesson that being Chinese in America required careful calibration, learning how to shrink myself, offering it in diluted forms, careful not to overwhelm. It wasn’t until the pandemic happened that I understood how early those instincts set in.

Cultural curiosity is not the same thing as cultural consequence. What a privilege it is, to be able to try on someone else’s identity for a day without inheriting any of the consequences. To pick out the parts that you like and adorn yourself with them, then to peel it off when you tire of it, hanging it up in the back of your closet to collect dust, already moving onto the next trend, the next bauble.

Traditional Chinese Medicine has existed for centuries longer than Western medicine, and yet, most of the people participating in the “Chinese time of my life” trend speak about these ancient practices the same way they speak about discovering a new overnight collagen mask. But social media has a way of doing that. It launders out history, flattening what used to be rich and alive into something frictionless and palatable. Everyone talks about the apple slices in warm water in their viral videos; no one mentions the bitter tree roots.

So what happens tomorrow, or next week, when a new trend inevitably takes its place? The videos will trickle off, the interest will fade. The “Chinese baddies” will move onto the next thing, and the room will look the same as it always has.

“Chinese” isn’t a time in my life you met me in. It's not something I get to leave behind when the attention shifts. It’s my past, my present, and my future. It’s what I carry, whether the world is paying attention or not.