Culture

Meet the Director Changing the Narrative of Black Women in America

Oge Egbuonu on the story behind Invisible Portraits.

26 June, 2020

10 November, 2021

Oge Egbuonu, director of the newly released film Invisible Portraits, is trying to change the narrative around black women. Egbuonu describes this film as a “love letter to black women,” where she interviews a range of black women, including scholars and authors, mothers and children, women of all ages, to explore both the centuries of contributions they have made to society that have gone unrecognized and their own personal experiences. “My intention from the very beginning was that I would continue to allow myself to be a vessel for these women and their stories,” she explains.

Egbuonu, a first-generation American born to Nigerian parents, did not have a traditional rise through the film industry. Her first passion was restorative yoga, which she was teaching in L.A. when a private client and major producer saw something in her and offered her her first break into the industry with his production company, Raindog. There, she worked as a producer for films such as Eye in the Sky and the highly acclaimed Loving. Through word of mouth of her abilities, Egbuonu got the opportunity to direct her current film, Invisible Portraits.

The film released last Friday, Juneteenth, and is now available for streaming on Vimeo. The timing could not have been more perfect, as America is more tuned in and willing to learn than ever before—a concept that is not lost on Egbuonu. “If you would have told me two and a half years ago, almost three years ago, that this film would be so timely, I would not have believed it,” she says.

Invisible Portraits is a history lesson, a story of personal revelation, a critique of society, a celebration, and a call to action wrapped into one 90-minute film. These stories and Egbuonu’s methods of conveying them are apparently so new to the public that both Sundance and Tribeca film festivals rejected the film because they failed to categorize the documentary—a shockingly poignant metaphor for the black experience. We sat down with the unbelievably talented Egbuonu to hear a little bit more about the process of making the film and why it is so startlingly important.

Egbuonu, a first-generation American born to Nigerian parents, did not have a traditional rise through the film industry. Her first passion was restorative yoga, which she was teaching in L.A. when a private client and major producer saw something in her and offered her her first break into the industry with his production company, Raindog. There, she worked as a producer for films such as Eye in the Sky and the highly acclaimed Loving. Through word of mouth of her abilities, Egbuonu got the opportunity to direct her current film, Invisible Portraits.

The film released last Friday, Juneteenth, and is now available for streaming on Vimeo. The timing could not have been more perfect, as America is more tuned in and willing to learn than ever before—a concept that is not lost on Egbuonu. “If you would have told me two and a half years ago, almost three years ago, that this film would be so timely, I would not have believed it,” she says.

Invisible Portraits is a history lesson, a story of personal revelation, a critique of society, a celebration, and a call to action wrapped into one 90-minute film. These stories and Egbuonu’s methods of conveying them are apparently so new to the public that both Sundance and Tribeca film festivals rejected the film because they failed to categorize the documentary—a shockingly poignant metaphor for the black experience. We sat down with the unbelievably talented Egbuonu to hear a little bit more about the process of making the film and why it is so startlingly important.

Photo: Courtesy of Oge Egbuonu

Photo: Courtesy of Oge EgbuonuThe subject of your film sits at the intersection of being a woman and being black. Can you explain what that actually means and why it’s so significant?

“I’m a black woman, so it’s significant to me because it’s me. I think that at the intersection of every ism that we’re experiencing is the black woman. The black woman tends to be the mule of the world. When you think about slavery and rape culture, when you think about the movements that have happened in this country, it all came off the backs of black women. When you think about the civil rights movement, Septima Clark, Ella Baker, most people don’t know those names and stories. They were the women who did the strategizing, the women who made sure that the communities were fed and educated, the women who sat down on endless nights with Martin Luther King and every other black man at the face of those movements. It was those women that made it possible for them to give those speeches. When you think about the Black Lives Matter movement, that was created by three black women. I wanted to create something that not only showcased that, but honored black women and held reverence for the contributions that they have made and continue to make.”

Like you said, these are stories that really haven’t been told, so you are creating a narrative that doesn’t currently exist as it should. How did that affect how you told these stories?

“In the research phase of doing this, I realized that what we’re taught in schools is revisionist history. In knowing and understanding that, I had to cultivate something that tells the truth, which is hard. Especially the first half of the documentary, it’s hard to sit through some of that. I do understand that, but it was necessary. It was a tightrope that I had to walk in how I cultivated and edited the film in being able to tell these stories. That process was very challenging.”

This is heavy subject matter. How did you balance the emotions that came with learning it and hearing it from the women you interviewed?

“The experience was hard. I dedicated six days to the research. Six days, 14 hours a day, and then on Sunday I would rest, but I couldn’t get out of bed. I would be in bed crying for hours and hours. I realized that I needed another outlet, which is why I put myself back into therapy. That helped a lot. Meditation helped a lot, and prayer.

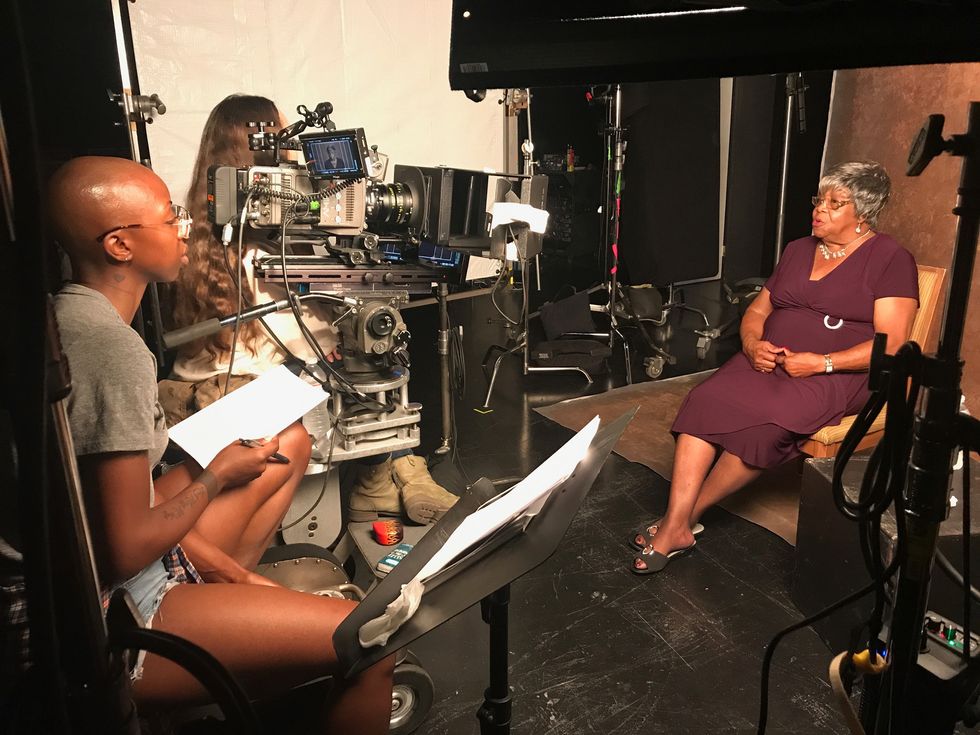

“I was also very intentional with the crew that I cultivated. It was a crew of all women. I really wanted that to bring a sense of softness and tenderness and grace to the set for these women that we were interviewing, to be vulnerable and to open up to us. There were many days that tears were shed. I could tell you how many days we didn’t cry versus how many we did, but it was a safe space for everyone involved. I tend to say that this experience was a rebirth for me. That’s the best way that I can summarize this entire experience from start to finish.”

“I’m a black woman, so it’s significant to me because it’s me. I think that at the intersection of every ism that we’re experiencing is the black woman. The black woman tends to be the mule of the world. When you think about slavery and rape culture, when you think about the movements that have happened in this country, it all came off the backs of black women. When you think about the civil rights movement, Septima Clark, Ella Baker, most people don’t know those names and stories. They were the women who did the strategizing, the women who made sure that the communities were fed and educated, the women who sat down on endless nights with Martin Luther King and every other black man at the face of those movements. It was those women that made it possible for them to give those speeches. When you think about the Black Lives Matter movement, that was created by three black women. I wanted to create something that not only showcased that, but honored black women and held reverence for the contributions that they have made and continue to make.”

Like you said, these are stories that really haven’t been told, so you are creating a narrative that doesn’t currently exist as it should. How did that affect how you told these stories?

“In the research phase of doing this, I realized that what we’re taught in schools is revisionist history. In knowing and understanding that, I had to cultivate something that tells the truth, which is hard. Especially the first half of the documentary, it’s hard to sit through some of that. I do understand that, but it was necessary. It was a tightrope that I had to walk in how I cultivated and edited the film in being able to tell these stories. That process was very challenging.”

This is heavy subject matter. How did you balance the emotions that came with learning it and hearing it from the women you interviewed?

“The experience was hard. I dedicated six days to the research. Six days, 14 hours a day, and then on Sunday I would rest, but I couldn’t get out of bed. I would be in bed crying for hours and hours. I realized that I needed another outlet, which is why I put myself back into therapy. That helped a lot. Meditation helped a lot, and prayer.

“I was also very intentional with the crew that I cultivated. It was a crew of all women. I really wanted that to bring a sense of softness and tenderness and grace to the set for these women that we were interviewing, to be vulnerable and to open up to us. There were many days that tears were shed. I could tell you how many days we didn’t cry versus how many we did, but it was a safe space for everyone involved. I tend to say that this experience was a rebirth for me. That’s the best way that I can summarize this entire experience from start to finish.”

Photo: Courtesy of Oge Egbuonu

Photo: Courtesy of Oge EgbuonuYou cover so many horrible moments in history, but there’s still joy and hope in the film. How would you describe the tone of the film?

“I tend to say that it’s a love letter to black women. I understand the first half of the film is very heavy. I hit you hard with a lot of information. I was very intentional in making sure that the film didn’t end that way. I wanted the audience, including black women, to leave a little bit uplifted, to leave inspired. To end it on the note of the beautiful section was very intentional. Even though we’re learning about this history that is very much so still present today, there’s also a lot of beauty surrounding black women back then and today. I wanted to make sure we highlighted that.”

You’re uncovering a lot of information many people think they know, but their knowledge only just scratches the surface. How would you advise people to dig deeper in their education?

“This society thrives off of living in imagination and conditioning. Most people don’t read books, and that’s where most of the education is. You’ve got to be able to do the independent investigation. When people are asking me: What can I do? What should we do next? How do I show up better? I can’t answer that for you. The first step is the internal work that you have to do. By you doing a deep dive internally, the answer comes to you. I can’t tell you how to show up for every black person or every black woman because it looks different for every single person. You have to do that work, and that’s the hard part. Self-reflection isn’t popular because it’s not easy. It goes back to what Scott Gale Hern said, ‘The revolution won’t be televised.’ He wasn’t talking about TV, he was talking about how it has to be an internal revolution first before you can fight for liberation of all externally.”

“I tend to say that it’s a love letter to black women. I understand the first half of the film is very heavy. I hit you hard with a lot of information. I was very intentional in making sure that the film didn’t end that way. I wanted the audience, including black women, to leave a little bit uplifted, to leave inspired. To end it on the note of the beautiful section was very intentional. Even though we’re learning about this history that is very much so still present today, there’s also a lot of beauty surrounding black women back then and today. I wanted to make sure we highlighted that.”

You’re uncovering a lot of information many people think they know, but their knowledge only just scratches the surface. How would you advise people to dig deeper in their education?

“This society thrives off of living in imagination and conditioning. Most people don’t read books, and that’s where most of the education is. You’ve got to be able to do the independent investigation. When people are asking me: What can I do? What should we do next? How do I show up better? I can’t answer that for you. The first step is the internal work that you have to do. By you doing a deep dive internally, the answer comes to you. I can’t tell you how to show up for every black person or every black woman because it looks different for every single person. You have to do that work, and that’s the hard part. Self-reflection isn’t popular because it’s not easy. It goes back to what Scott Gale Hern said, ‘The revolution won’t be televised.’ He wasn’t talking about TV, he was talking about how it has to be an internal revolution first before you can fight for liberation of all externally.”

Photo: Courtesy of Oge Egbuonu

Photo: Courtesy of Oge EgbuonuYou also focused a lot on archetypes and social constructs. How did you go about describing the significance of them in the film?

“It became so relevant as I was doing the research how prevalent these social constructs and stereotypes were. Most people are guided by them, mainly unconsciously. When you think about it, black women are viewed through the lens of those stereotypes. Look at Aunt Jemima. Look at the Jezebel and the sexualization of black women that leads to the murder of black women. I was creating space to give voice to those, but doing so in a way that people could understand what cultivates the stereotype, which are the social constructs. This entire society that we’re living in right now is a social construct. We’re on the phone because someone thought that to be true. We have magazines because someone had an idea. Everything that we’re experiencing as reality came from a thought. I wanted to use the documentary to really nail that point in and motivate people to start to do the deep dive and ask the questions rather than just accepting what they’re told to be true.”

I learned so much that I was embarrassed I didn’t know before:

“That was me, too. I get it. I’m a black woman. Sixty percent of what’s in this film, I had no clue about prior to making this film—no clue. I went through the first few months of just real disappointment in myself, being like, How did you not know this? But then I also realized I wasn’t taught it. You don’t know this unless you go to school and you study African-American history or you’re a historian. You realize this truly is revisionist history. They give you the beautiful parts of what they polished. It also makes you question once again, who is writing the history books? For me, all of this is about questioning what we’ve been taught.

What is the biggest thing you want people to take away from these stories?

“I think the biggest thing to take away is the contributions that black women have made and continue to make, and that people should start to hold reverence for black women.”

Top photo: Ryan Eng

Want more stories like this?

Producer Sylvia Zakhary on the Value of Authentic Storytelling

Brandon Kyle Goodman on the Art of Conscious Art of Anti-Racism

Aurora James on the 15 Percent Pledge and Why It’s More Important Than Ever

“It became so relevant as I was doing the research how prevalent these social constructs and stereotypes were. Most people are guided by them, mainly unconsciously. When you think about it, black women are viewed through the lens of those stereotypes. Look at Aunt Jemima. Look at the Jezebel and the sexualization of black women that leads to the murder of black women. I was creating space to give voice to those, but doing so in a way that people could understand what cultivates the stereotype, which are the social constructs. This entire society that we’re living in right now is a social construct. We’re on the phone because someone thought that to be true. We have magazines because someone had an idea. Everything that we’re experiencing as reality came from a thought. I wanted to use the documentary to really nail that point in and motivate people to start to do the deep dive and ask the questions rather than just accepting what they’re told to be true.”

I learned so much that I was embarrassed I didn’t know before:

“That was me, too. I get it. I’m a black woman. Sixty percent of what’s in this film, I had no clue about prior to making this film—no clue. I went through the first few months of just real disappointment in myself, being like, How did you not know this? But then I also realized I wasn’t taught it. You don’t know this unless you go to school and you study African-American history or you’re a historian. You realize this truly is revisionist history. They give you the beautiful parts of what they polished. It also makes you question once again, who is writing the history books? For me, all of this is about questioning what we’ve been taught.

What is the biggest thing you want people to take away from these stories?

“I think the biggest thing to take away is the contributions that black women have made and continue to make, and that people should start to hold reverence for black women.”

Top photo: Ryan Eng

Want more stories like this?

Producer Sylvia Zakhary on the Value of Authentic Storytelling

Brandon Kyle Goodman on the Art of Conscious Art of Anti-Racism

Aurora James on the 15 Percent Pledge and Why It’s More Important Than Ever