Now, I Wear My Last Name Around My Neck

Me, a toxic boy, and my complicated relationship with my nameplate necklace.

My nameplate necklace broke off in the dorm room of a boy I really liked but now realize was bad for me. At the time, I wore "Bianca" around my neck because it was easy to pronounce, it was white, and I was happy to have a name that was not the most common, but not the most obscure. I haven’t met that many Biancas in my life, which is good because when I do, I feel an inexplicable amount of disdain, which is (obviously) unreasonable because one cannot own a name; it’s not and never will be mine and mine only. Back then I would wear vintage Levi jeans with Forever 21 crop tops, Blundstone boots, and my first name before it was lost. It was a different time (2016). The boy returned it to me at the one bar in town on burger night, in front of a group of girls as they gawked. I felt so cool as my name sat in the palm of his hand after he had carried it around in his wallet, waiting to find me. He later told me that he considered keeping it, fixing it, and wearing it himself which, as a nineteen year old, was the most romantic thing I had ever heard and now, as an adult trying to put less stock in what men think and not get so sucked into the words they say just for the sake of saying words, think of as one of the many performative things he has done.

But boys didn’t like me at my mostly-white New York City private high school, unsurprisingly and for daringly obviously racism-related reasons. They would make fun of my last name, Asare, and its adjacency to the word "sorry," asking questions like, “Do you wish you were white like your mom?” So, getting to my Hudson Valley liberal arts college and realizing that boys thought I was cute, and the way that particular boy would say my name in a fake British accent when we were nineteen years old, was exciting.

Then, at twenty-two and without a pronunciation lesson, he started calling me by my last name. Now, I wear my last name around my neck. And it’s not because he was so special or influential, but because, unfortunately, a white boy saying my West African last name with no undertone of a joke was everything to me at the time.

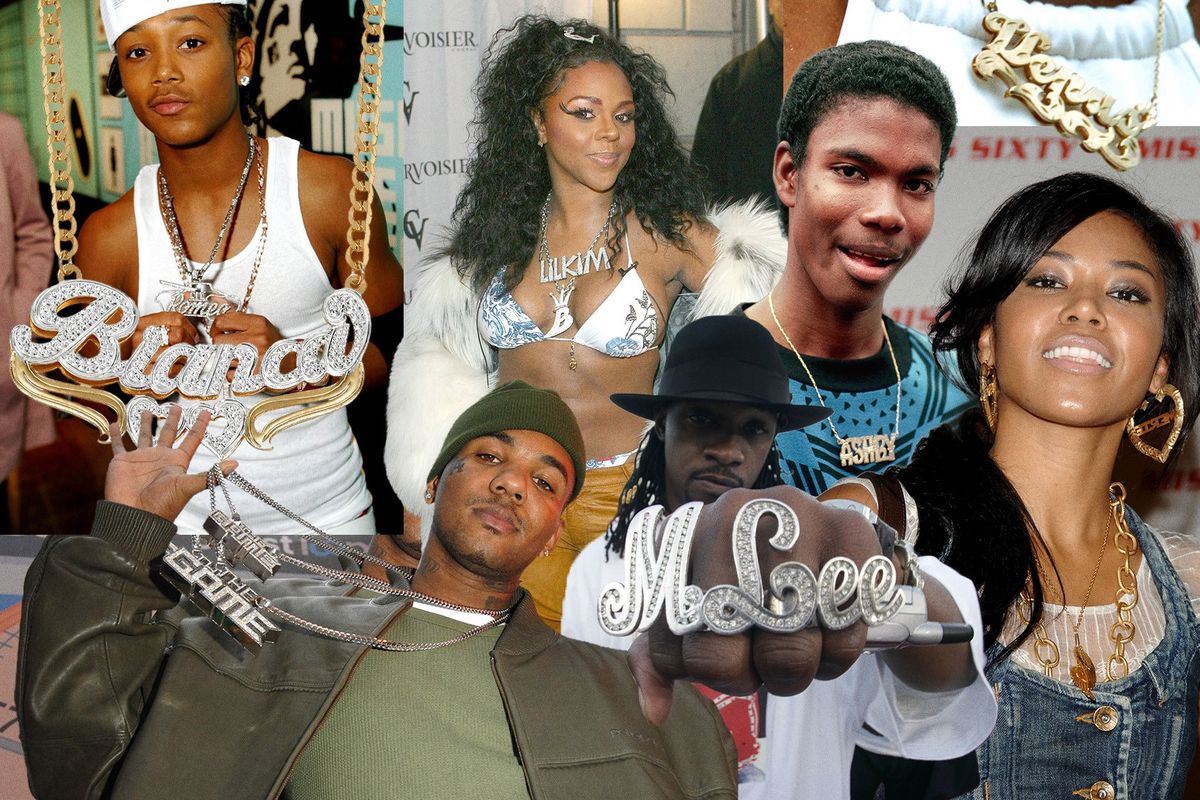

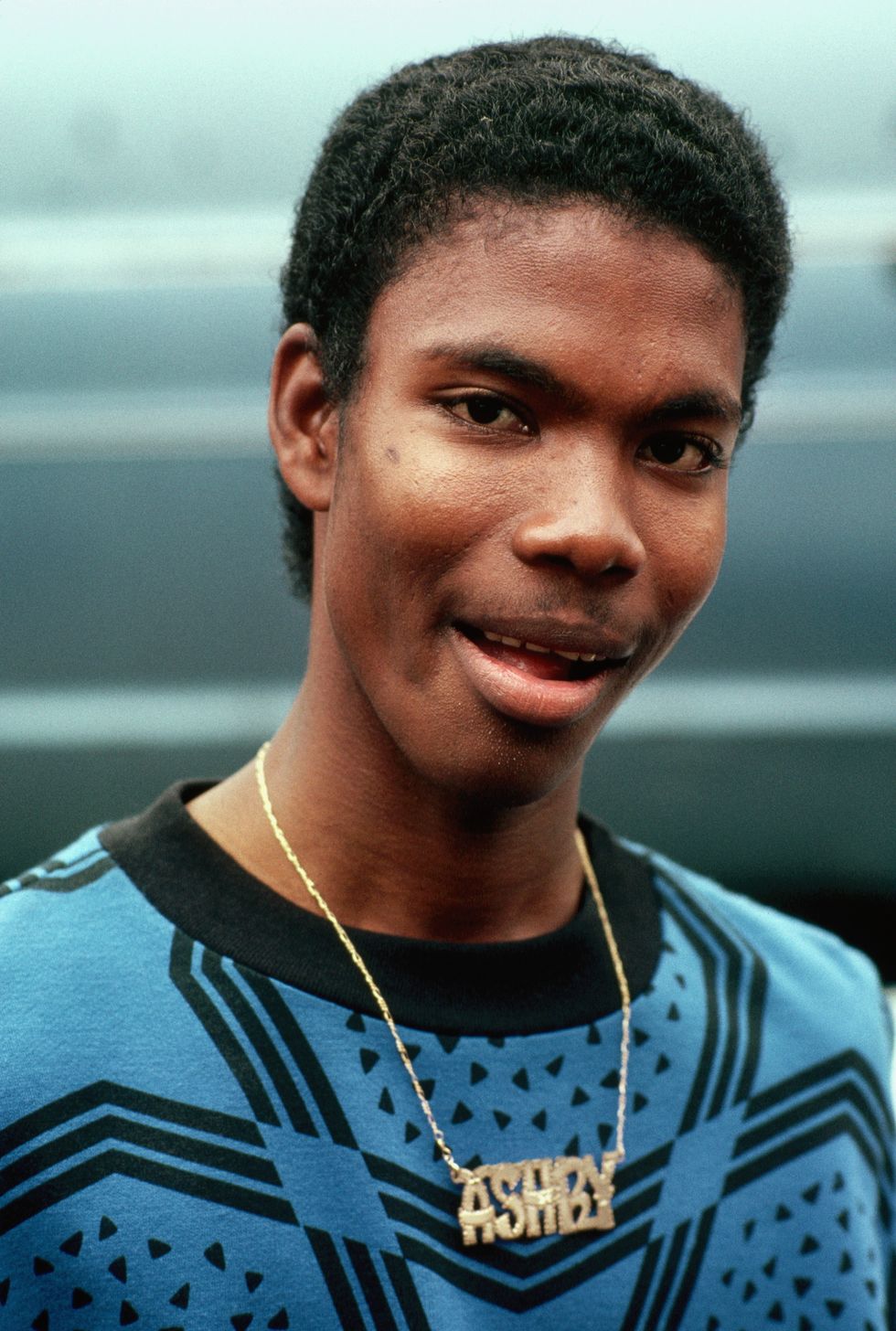

Getty Images

Cultural anthropologist Marcel Rosa-Salas and writer Isabel Flower spent six years collecting first hand anecdotes and experiences to create a book that maps the history and significance of nameplate jewelry. In the book, "The Nameplate: Jewelry, Culture, And Identity," historian, archivist, and Brooklyn native Professor Q credits nameplate jewelry to the 1970s—Teddy Pendergrass and Barry White, in particular. Then, in the 1980s, due to hip hop’s influence on fashion, the trend made its way down to Brooklyn and was embraced by the African-American and Latino communities. “The nameplates at that time were the huge, flat, rectangular B-boy style; they were four or five inches long and maybe two inches high,” he writes. They announced your presence before you spoke. And in Black and Brown communities, they were declarations of pride, a way to reclaim ownership of your own self. I think, both now and in the ‘80s and ‘90s, the oversized announcements of names was a way of healing.

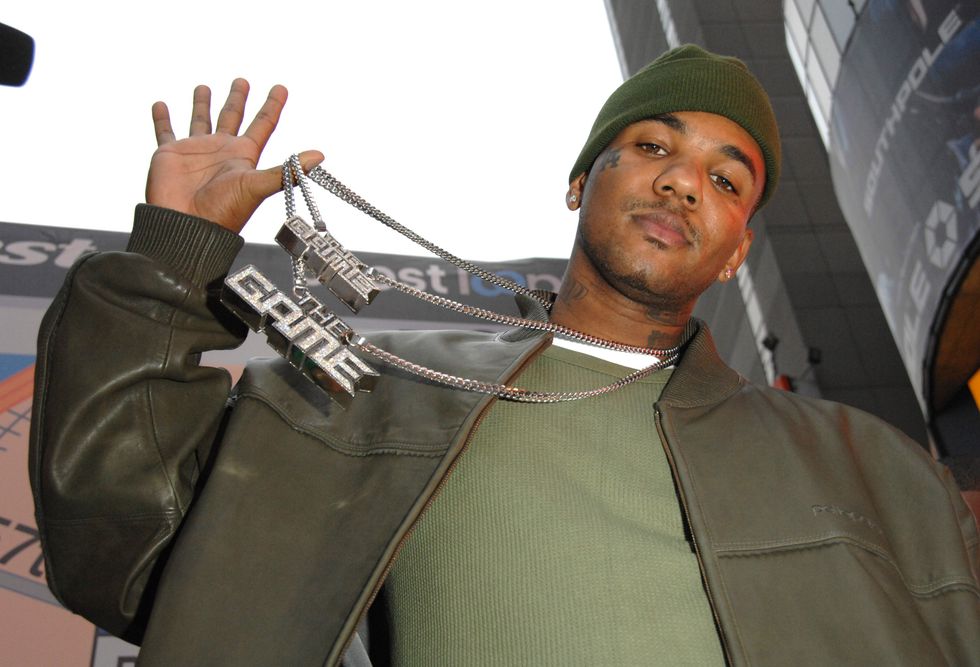

Since then, the popularity of nameplate jewelry has only grown, thanks, in part, to pop culture: Spike Lee’s films “She’s Gotta Have It” and “Do The Right Thing” (in this case, to communicate a clear message), and of course, on Carrie Bradshaw in “Sex And The City,” who brought the “trend” to a white, mainstream audience with no acknowledgment of where it originated, as often happens. “Nameplates became part of popular fashion through the mass marketing and globalization of hip hop music, culture, and style, and because of the way mainstream media consistently sources creative inspiration from communities of color,” Rosa-Salas and Flower tell me.

Asare, depending on the particular dialect, means “warrior” or “to be strong.” But, as a little Black girl in mostly white spaces, all I heard was that it wasn’t English, wasn’t white, wasn’t easily pronounced, so it felt like there was everything to make fun of. Had I even known what it meant as a kid and had I even shared that meaning with those boys, I doubt it would have mattered.

Scholar, curator, and community arts educator Jillian Hernandez wrote this: “The nameplate is a performative object whose stage is skin surface and whose affect is love. A gift to oneself or others, it proclaims: You belong, we recognize you.” And I think, with Asare around my neck, I am continuously proclaiming that to myself. It’s an affirmation, exposure therapy, assertion, and personal style choice all at the same time.

Getty Images

Getty Images

I think that, in a political climate where people make unapologetic takes about who deserves to exist based on what they look like and where they come from, openly promoting the non-American parts of myself is important. For me, now, my nameplate necklace is about inviting questions about my name and conversations about who I am that I was afraid of having before. With Rosa-Salas and Flowers’ book in front of me, I committed to learning as much about nameplate jewelry and their role in Black culture as possible and, in turn, as much about myself.

"Do The Right Thing"

IMDB

This has been part of a bigger shift for me. I’m the child of immigrants, grew up in primarily white spaces, and I’ve only recently realized how disconnected I am from Black American culture because, despite technically being a Black American, I didn’t grow up in a Black American household. Recently, I rejected my chemically straightened hair, got a big chop, and started my natural hair growth journey. Now, I have tooth gems and my hair is either naturally coily or in braids; I bleached my eyebrows despite the fears of what that might mean for my already non-Eurocentric self. And now, of course, I wear my West African last name in silver letters against my collarbone. To me, and based on who I am and who I was, it is revolutionary.

Getty Images

I’m someone who can’t remember to put my jewelry on, despite and maybe because of my mom always insisting that a real woman never left home without earrings on, whatever that means. So my jewelry, always silver and never gold, stays on until they are part of me, until they’re tarnished and have to be removed. I wear my nameplate necklace until I can’t stand the mispronunciations or the feeling of something around my neck anymore. More than anything and most of the time, I’m happy, confident, and proud. I want to talk about my name, about being a first-generation American, about Ghana and about having a white grandma who lived in Ghana and about all the questions I will never get to ask her about that experience. At other times, I feel the overbearing weight of everything it carries from my childhood self, and want nothing to do with it.

Getty Images

So, my nameplate necklace broke off in the dorm room of a boy I really liked. The saddest part is, at the time, I would have given him my first name if he had asked for it. But my relationship with my own name has changed. Now, despite having a complicated relationship with it, I would never, ever let anyone take my last name from me. Because it’s mine—not for someone to find, keep, and wear as their own. Not for anyone to find humor in, despite not knowing the meaning, the origins, and the weight it carries. I deserve to feel some sense of ownership over it—something I couldn’t give myself at nineteen, but can claim for myself now.