Did The Algorithm Kill Personal Style?

On finding our personal style in the age of the algorithm.

The peak of the micro trend came in 2023, back when “aesthetic” stopped describing what something looked like and started meaning that looks good. Suddenly, aesthetic had a vibe, and every vibe was attached to the word “core", and the internet developed a new code to identify trends, the ones that came and went within weeks to months, or never took off in the first place. The algorithm became a graveyard for fleeting trends that made no sense in the context of real life and were built on almost fictional personas, like “office siren” and “ballet core.”

The death of personal style in the age of the algorithm is a topic that has spurred plenty of discourse over recent years. Technology’s accelerationism has had a profound impact on the trend cycle and, subsequently, our wardrobes, making even the most trend-agnostic amongst us occasionally fall victim to the new hot thing on a late-night TikTok scroll. And over the course of the years, it’s become increasingly difficult to decipher if someone dresses a certain way out of authenticity, or if it’s just because their screen time is averaging 7+ hours a day.

Personal style used to be a vessel for self expression. We dressed the way we did to signal to others what our interests were, what we cared about, how we saw ourselves and the world around us, and how we wanted to be seen. To have an understanding of your personal style is to know yourself and to let others know you. But what happens when our screens take over, and self expression becomes more about cultural relevance and being “on trend” than it does one's true self? Is the algorithm’s echo-chamber holding personal style hostage?

These days, many of us are no longer participating in the actual subcultures that once shaped our identities (and our closets). Instead, we’re regurgitating the kinds of sartorial codes we think we might enjoy, based loosely on the subcultures we are no longer, or never were, a part of. For Prada’s Spring/Summer 2025 show last September, Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons referenced this perfectly with a collection that was largely inspired by the power the algorithm holds over fashion today. “We are directed by algorithms, so anything we like and anything we know is because other people are instilling it into us,” Mrs. Prada told Vogue.

Prada Spring/Summer 2025

Getty Images

Prada Spring/Summer 2025

Getty Images

Not everyone has surrendered to trying to keep up with the scroll. Tish Weinstock, an editor and the author of “How To Be A Goth: Notes On Undead Style”, and Olivia Singer, British Vogue contributing editor, have both become known for their immovable sense of style. “I think we’ve seen a rise in signature looks because of our increasing calls for authenticity and the normalization of self-acceptance,” Weinstock says. “People are more interested in feeling comfortable in their own skin as opposed to conforming to trends.” Singer agrees, but sees the democratization of fashion—as anyone with a phone in their bedroom can critique designer debuts and collections—as a double-edged sword: “Trends emerge and die quicker because we are so bombarded with visual information online," she says. "That’s why everyone keeps going back to the archives—we’ve run out of newness, particularly during this curiously fallow creative period.”

These days, true authenticity can feel hard to pinpoint when everything is a reference. For Calvin Klein Collection’s Fall/Winter 2025 show back in February (and Veronica Leoni’s first since Raf Simons left the brand in 2018), much of the criticism towards the collection was that it felt too referential to the Calvin Klein Collection of the ‘90s, just one season after the aforementioned Prada show which repurposed prints and silhouettes from the archives.

With this in mind, we can look at the boom of micro-trends as the result of two things: a form of escapism, and as an identity-seeking exercise. Much like how someone chronically online inevitably starts using TikTok slang, our wardrobes have become reflective, too, of our online engagement. We’re used to using corners of the internet to escape the real world and, ultimately, lean into nostalgia as a way to cope with our current socio and geopolitical climate. When our identities are increasingly informed by what we see online—whether it’s mob wives, coquettecore, or the tomato girl— our style choices are close to follow. And with ample references and access to jarringly fast fashion, it’s easy to portray a version of yourself you want to be every other day, rather than take the time to hone in on who you actually are.

It wasn’t always like this. Back when online shopping took weeks to ship and t-shirts cost more than a deli sandwich, we had to spend more time thinking about who we were and how certain clothing items fit into our lives. At the very least, an impulse purchase may not feel the same if you had to wait one month to receive it in the mail. Now, with same day delivery and the Sheins and Fashion Novas of the world producing garments as cheaply and swiftly as possible, experimenting with personal style has gone into overdrive—hence the lightning-fast birth, and death, of the micro trend cycle.

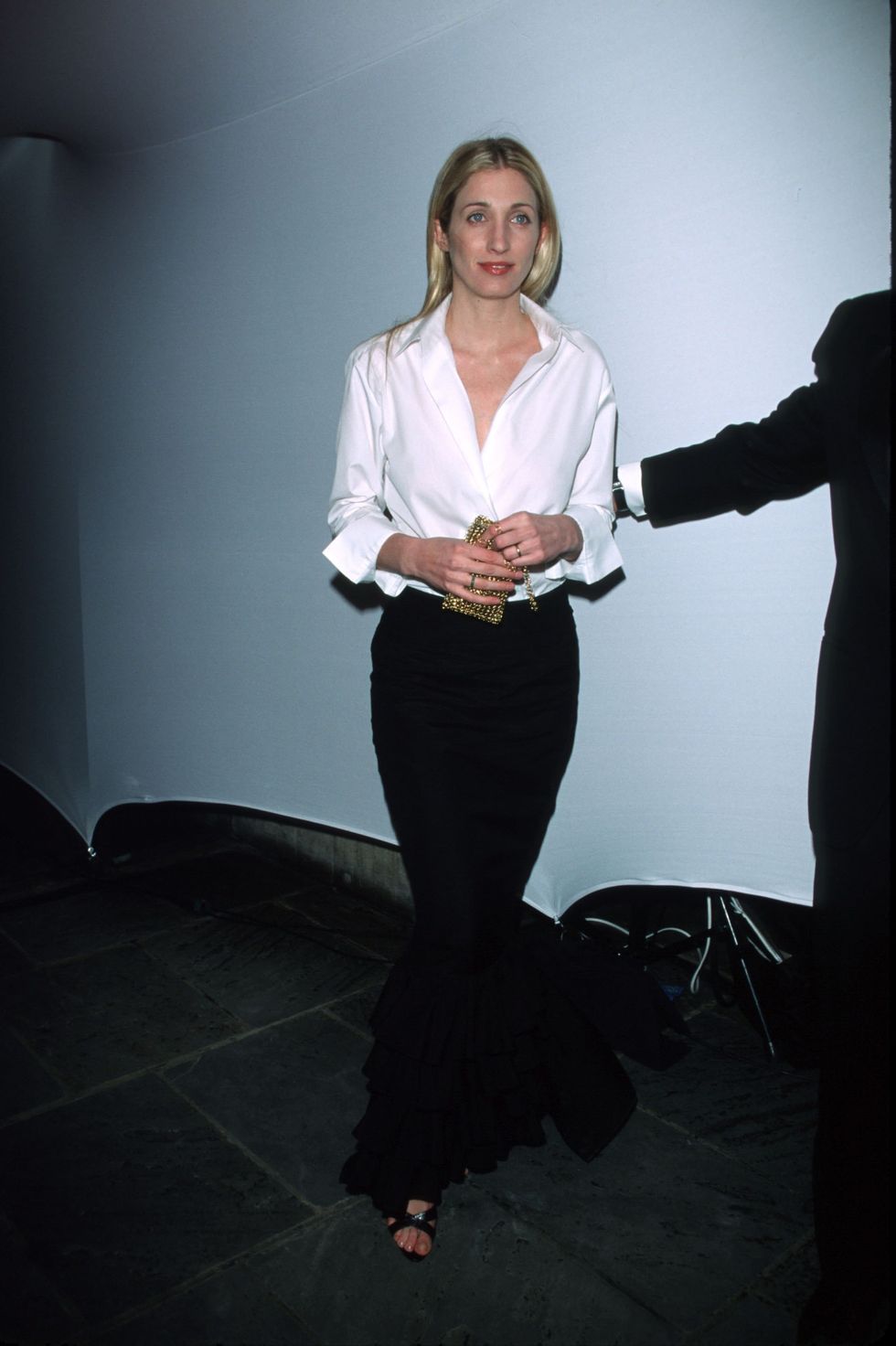

Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy

Getty Images

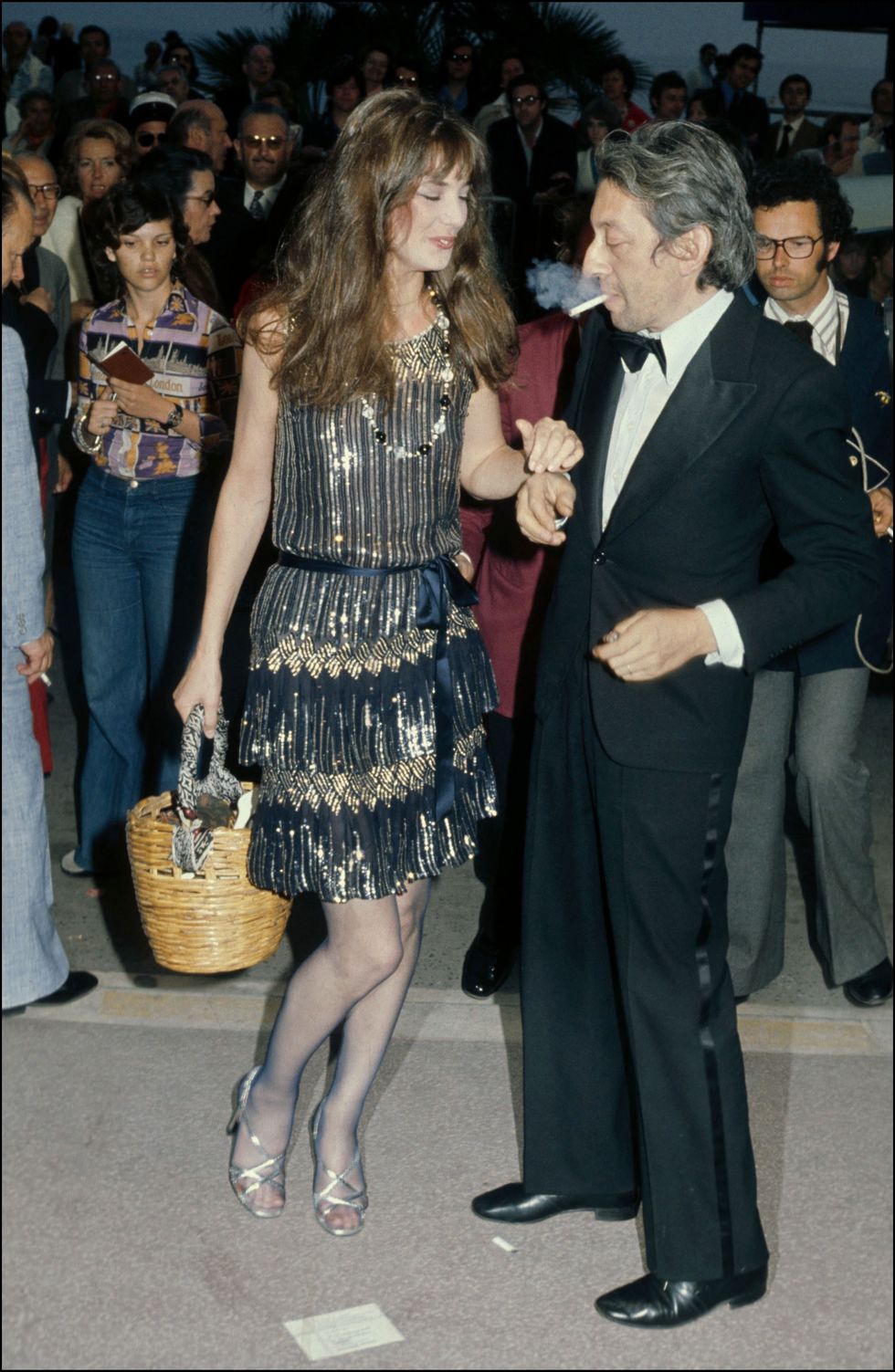

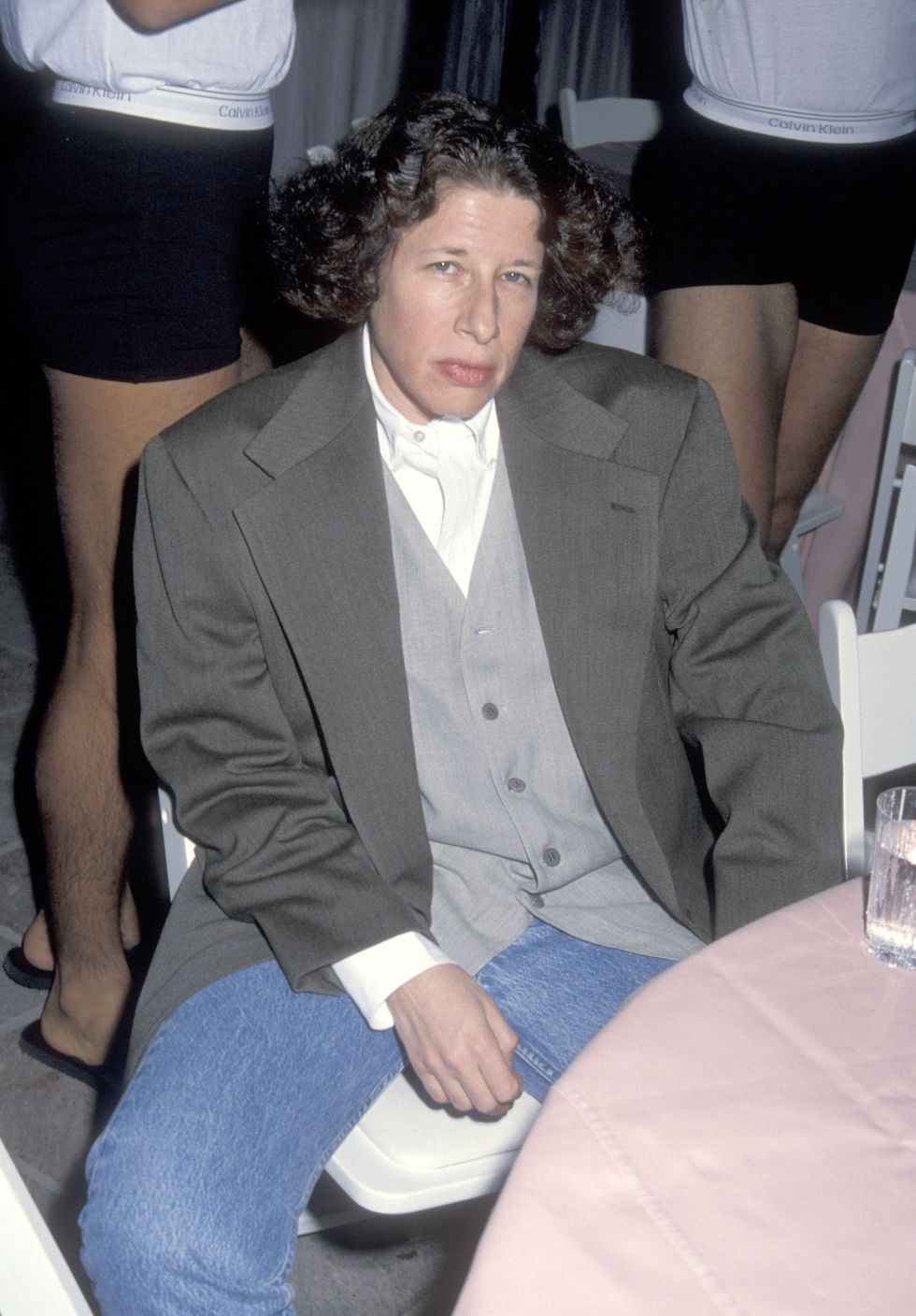

Before social media turned style into content, some of our personal style greats—Fran Lebowitz, Jane Birkin, Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy—developed their personal style based on life experiences. Naturally, trends somewhat informed this: Birkin’s fame peaked in the ‘60s and ‘70s, reflected in her bohemian French style sensibilities; Bessette-Kennedy’s ‘90s minimalism was understated partly because of the time, and partly because of her role at Calvin Klein; Lebowitz’s iconic uniform is tactfully based upon her agnosticism both towards trends and towards change in general (she still reportedly does not own a cell phone).

Singer recalls an interview with Shirley Manson, who told her that getting ready for a red carpet used to feel like how young women got ready to go to the club, borrowing things off each other and helping with their own hair and makeup. ”Now it's an entirely different production, and it’s harder to tell who has good style, and who has a good stylist,” she notes. “There’s something so compelling about when things were more instinctive and lo-fi, and I think that's how you are more likely to end up with legitimately good, interesting personal style.”

Jane Birkin

Getty Images

Fran Lebowitz

Getty Images

Some might say the positive side of all this is the democratization of fashion’s old gatekeeping systems. Instead of the singular, monolithic sources that used to dictate trends, like print magazines and its editors, the internet’s insatiable appetite for the archives, nostalgia, and reinvention can lead to a sense of style liberation. “With the wealth of references available, people are discovering more sources of inspiration, which is exciting, as it means we won’t all look the same,” Weinstock says. “It’s also allowing for personal style to become more fluid. I take inspiration from a broad spectrum of references, which means my style might look different from one day to the next, [but there’s still an] overall sense of continuity.”

There’s also the lesser-discussed topic of the business of personal style, and what that means in a paradigm where many individuals are making a sizable living by simply dressing “well” for the internet to witness. In which case: does personal style lose all meaning, or gain a new one? “I think being online has helped people cultivate their personal style because they’re dressing up for a larger audience than they would have if they lived permanently offline,” Weinstock counters. “People understand it's a business now, and are far less judgmental about that—at least among my community, there's very much a feeling that if you dress well, and you're using that to get paid, then good for you,” adds Singer.

These days, folks who are interested in fashion don’t need to go to school to get a degree before working at a magazine, or assist on sets before becoming a fashion photographer, or sign with an agency before becoming a model—all they need is a phone and good lighting. This thought is both jarring and liberating, especially when positioned against an industry that is particularly well-known for gatekeeping. And perhaps therein lies the point. Are we mostly just frustrated that an industry that once profited from dictating trends is losing its grasp as the ruling class of fashion?

Maybe we’re missing the point and the problem isn’t that personal style is dying, or that the algorithm is the villain. Maybe it’s that we’re too overwhelmed by the overflow of content in our daily lives to spot authenticity when it does show up. And who can we blame for that?