Prêt-à-Porter Is the ’90s Fashion Time Capsule You’re Missing

A look behind the scenes of Robert Altman’s fashion industry imbroglio, 30 years later.

It’s 1994, Paris Fashion Week, and a 70-year-old Robert Altman is at the center of the action. He’s got multiple cameras running back and forth between runway shows like Miyake and Mugler, A-listers including Julia Roberts and Sophia Loren improvising characters who are largely being rewritten on the spot, and Miramax producer Harvey Weinstein in his ear wondering if this is how his $20 million is getting spent.

If it sounds a bit like a trainwreck, it was—and the resulting Prêt-à-Porter (Ready to Wear), is a bit of a star-studded stain on the vaunted reputation of the seven-time Academy Award-nominated M*A*S*H, The Long Goodbye, and Nashville auteur. But what critics, and general audiences, found the film lacked in depth, intrigue, and incisiveness, it today makes up for as a time capsule of the apex of ’90s fashion. Simply put, everyone who was anyone is in Prêt-à-Porter (or was, like Karl Lagerfeld, mad about it), and for the scale of spectacle alone, modern fashion audiences are overdue for its revival.

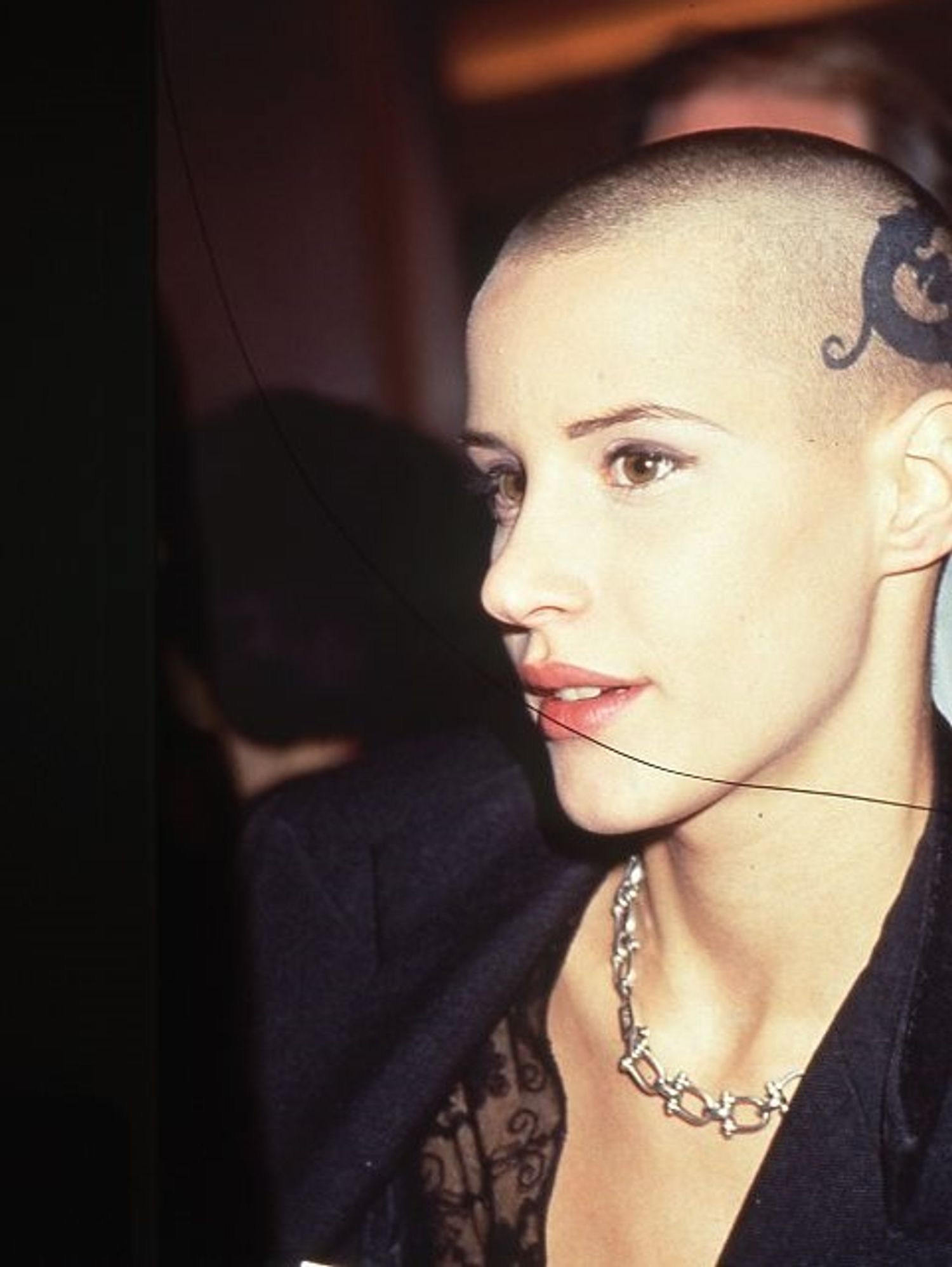

Courtesy of the Robert Altman Collection, The University of Michigan Library, Special Collections Research Center

Courtesy of the Robert Altman Collection, The University of Michigan Library, Special Collections Research Center

“Prêt-à-Porter is the ultimate example of what is true about the best of film: that an audience can—and often should—be rarefied, or in modern parlance, targeted. Movies don’t have to be for everyone,” screenwriter, producer, and former creative director Patrik Sandberg, told me. “Altman understood the anthropology of subcultures and used his own access to not only pay affection toward them but satirize and expose them in a ritual of embarrassment. [...] You either get it or you don’t.”

Still, there are others who would suggest Altman didn’t quite “get it” either. I spoke to Prêt-à-Porter screenwriter Barbara Shulgasser-Parker, who kicked off our interview by saying, “If you're looking for someone to tell you, ‘Oh, no, it's really great, and the critics got it all wrong,’ you're talking to the wrong person.” Shulgasser-Parker, who penned an incredible tell-all for Vanity Fair back in 1994, conjured the image of a director treading water, caught between a glut of celebrity, critical scrutiny, and complications due to cardiomegaly. “When I arrived in Paris for the shoot, [Altman] was absolutely gaunt and he took a lot of naps during the shoot.” She gave an example of the director completely missing the action:

Courtesy of the Robert Altman Collection, The University of Michigan Library, Special Collections Research Center

“There's a scene in which [actor Marcello Mastroianni] is trying to get a bellhop to open a door, pretending it's his hotel room. I watched that scene being shot 20 times, right behind the camera, so I saw exactly what Marcello was doing. It was a very funny scene because the bellhop was comically short, and Marcello was shrugging and moving his hands around at waist level, doing every fantastic, hilarious, comic Italian gesture in the book. I was doing everything I could to not laugh because it was so genius. Then, when I saw the dailies the next day, the whole scene was shot from his chest up. Nothing he was doing with his hands was in the shot. I thought, ‘No, that they cannot have missed the entire comic performance.’ But it was like that every single day, from my point of view.”

On the other hand, while the results may have been wonky, Shulgasser-Parker described a dazzling ten-week on-set experience that sounds like the stuff of both film and fashion dreams. Lunches with Mastroianni and Harry Belafonte, who Shulgasser-Parker described as “possibly the most charming person I had ever seen,” attending countless shows with Altman for research, even sneaking around with actors in order to develop dialogue the director may have ditched… “All of the stories about the making of the film are what really capture the romance and daring of the fashion world itself.”

On this, Sandberg, who wrote his “most impassioned Letterboxd review about this movie,” would agree. “Fashion is slapstick, arcane, and mosaic, full of gravity and vapidity in equal measure. It’s also monumental, as is Altman.” At the end of the day, a fashion insider turned screenwriter who reveres the film and a film critic turned fashion screenwriter who hasn’t been able to watch it since tepid previews 30 years ago seem to capture the Prêt-à-Porter divide perfectly; could film ever fully capture the fashion world, could the fashion world ever truly love an outsider’s film?

Not to “both sides” the issue here, but if the behind-the-scenes photos we obtained thanks to the Robert Altman Collection at the University of Michigan and field librarian, curator, and archivist Philip Hallman were the only things to survive—the film is, after all, somewhat difficult to view after the implosion of Miramax—both cinephiles and couture aficionados must admit: whether we’re talking about the product or the process, there’s simply nothing else like Prêt-à-Porter.

Want more stories like this?

'Dune: Part Two' Does a Great Job Dressing Up Men’s Worst Fears

Margot Robbie and Andrew Mukamal Immortalize the Visual Feast of the Barbie World Tour in Newly-Launched Book

The Best ’80s Moschino Is in an Italian Slasher