This New Novel Explores What It Means To Mother and To Be Mothered

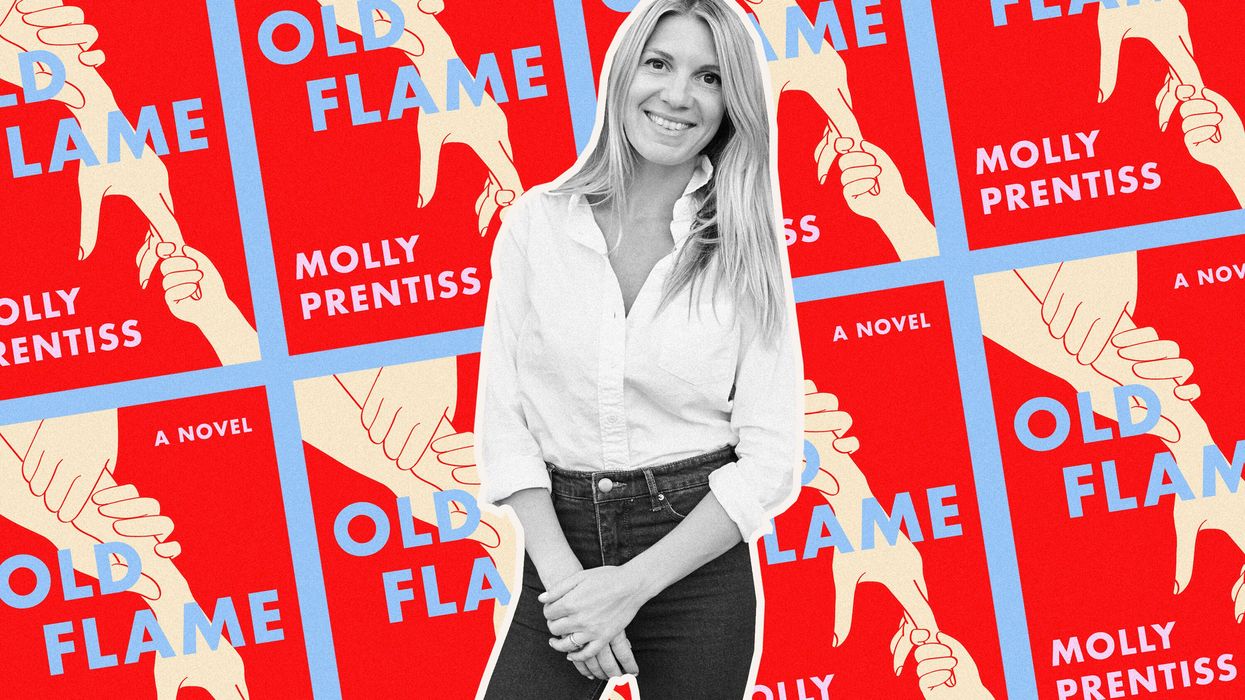

The author opens up about her sophomore novel "Old Flame."

Molly Prentiss's sophomore novel Old Flame launches a stunning exploration into contemporary womanhood. We follow the book's narrator, Emily, a copywriter in New York City, from the corporate workplace into the depths of her imagination. As Emily confronts a series of turning points—a fallout with a close work friend, Megan, a reunion and reckoning, a diverging relationship, and ultimately, an unexpected pregnancy—she takes readers on a journey around the world to better understand her place within it personally, professionally, and artistically.

While fictional in nature, Old Flame was born from a very real concern: how—and who—do we choose? The seed of the book began as a short story, "Eravamo Noi" (initially published in the Los Angeles Review of Books), which Prentiss wrote in a fitful moment after giving birth to her first daughter. She had returned to work but was still in "deep caregiving mode." "I started seeing this incredibly vast discrepancy between the work I was doing as a copywriter and my work as a caregiver and a mother—and sometimes they were right up against each other," Prentiss says. "I would be writing an email about selling a water bottle, then I would have to breastfeed. I saw how much my work world and the corporate world did not consider the female experience and the experience of a new mother."

With richly-drawn characters and searing honesty, Old Flame is an ode to life. It's about embarking on new chapters and closing others. It's about people—those who raise us, change us, love us, leave us, and ignite a flame so that we may keep turning the pages. As Emily muses at one point: "I thought about how women looked at each other and themselves, how they saw their own reflections in each other's gazes, and found themselves in each others' stories."

Ahead, Prentiss shares more about her writing process, the realities of creative living, and modern motherhood.

Very early in the book, Emily reads Barbara Ras's poem "You Can't Have It All." I was struck by this introduction to Emily's literary sensibility, and I wanted to begin our conversation with art, grief, and parenting, which are carefully explored in Old Flame. What has writing taught you about what it means to mother and be mothered?

“Oh my gosh, that's such a good and complex question. Writing allows me to dive into it in a way that makes meaning for me. I was thinking about this before we talked: one of the big projects of this book was to figure out if art could give way to meaning when it relates to the female experience, especially mothering and being mothered. Things that so often go unseen are not ripe for being a story. I think many parts of being a mother—being a woman, too—are pretty banal. They aren't ripe for narrative. I found this so interesting when I became a mother.

“I had all these experiences, and I didn't know how to tell them to people because they weren't funny or necessarily interesting. They weren't me coming to a realization or making changes as we want our characters to do. I was so used to telling stories; these were moments of repetitive action and daily activities that existed in a stasis that was beautiful in its own way, but it didn't allow me to tell its story. I wanted to figure out if I could narrativize this experience and make it interesting. Could I turn it into art?

“Emily's sensibility as the narrator is to reach for these other artists and writers–especially women whose experiences can help her make decisions– to feel less alone and inform her. That's always been my way. These other artists and writers have always been beacons for me of how, not only to make sense of what's going on in life, but also how to live a creative life—while also living in reality. There's so much [of that idea] in this book: How do you explore living an authentic creative life while having health insurance? Doing these sorts of mundane things you need to do for "real life," and the push and pull, especially when a kid gets involved and that responsibility amplifies. The practice of finding your own creative path and trying to squeeze it into the capitalist system is a “square peg in a round hole.” The way our society is designed is not conducive to creative life unless you can master both at the same time. I think Emily goes through that. I think a lot of us go through that.”

On the subject of creativity, I'd love to also talk about private writing. There's an element of private writing that upends Emily and Megan's relationship. I recently wrote an essay about journaling and how it can feel so nourishing—but also scary—in an age that demands we give so much of ourselves. Old Flame takes place in contemporary times, and I wanted to know if it was a conscious decision to put Emily's personal writing in a journal rather than an anonymous social media account or a drafted email.

“Well, there's [Emily's] reasoning for it, which is that HR could see everything that she writes on her screen—which was always something I found so creepy about working in corporate environments: your screen area is actually not yours. But I think you're correct to assume that beyond that, there's something about being inside a journal that invites more privacy or different writing. I also think that Emily's situated in this interesting time—kind of the same time that I was growing up and learning I wanted to be a writer—which is the generation that grew up writing in diaries then transitioned around college to computers and cell phones.

“Simultaneously she's living in gentrifying Williamsburg in the 2010s. She was there in the beginning: she saw the remnants of ['80s/'90s] artist Williamsburg and DIY loft living vibe, and her boyfriend is still pining after her and trying to hold on to that as the neighborhood shifts into this shopping mall, Disneyland version of itself. A part of Emily is searching or digging for ways to feel authentic to herself and private and make tangible things in the world—I think the physical journal has something to do with that. There's reaching [for] some nostalgic element or sometime before sharing everything was the norm. She's trying to figure out how to maintain some of that in her life, especially in her writing life.”

You cast such vivid descriptions of place—from corporate offices to homes with ceilings filled with angels—especially as Emily navigates some intense moments. At one point, you write: "The hotel's ornate Italianness suddenly felt oppressive. I craved a minimalism I knew I wouldn't find here. I wanted to pare everything down. My thoughts, the drapes, the thing living inside me. I wanted to give the world an enema. Flush everything away." And later: "I was seething on the subway, barely managing my nausea, watching the people around me supplement—or perhaps supplant—their consciousness with content from their various devices. ... We were each alone with our own pros and cons, zooming towards our cubicles, where we would labor for the next eight hours, shoving our personal baggage waaaay down, swallowing it when it rose in our throats like vomit, so we could email, email, email, until seven in the evening, at which point the sun would have lowered behind the tall buildings and our spirits would be sufficiently crushed..." Can you talk about the decision to place Emily mainly in New York and Italy?

“The scenarios I explore in this book each have something to do with family and the creation of a family that doesn't exist for Emily. I was pulling around my own experiences and the places where I had felt a sensibility of a family, and what the different versions of that felt and looked like down to the details. One of the things that I found so fun and fascinating about writing about the corporate world is how it is designed to do what it does, which is to feel like a family. People talk about their work teams as their families: their work wife and work sister. I wanted to render the team as having a motherly boss or manager. There are corporate father figures at the top who are distant but ostensibly give you everything you need to survive.

“There's this design of a built-in feeling of connection or need that really does work—which isn't to say because it's designed, it's not real. I do feel like so many of the relationships I've built in work situations are so deep and genuine, and they're simply based on proximity. That's how they often start. But I do think that the design of the system is to make you feel the need to stay and not leave the herd. So there's this built-in sensibility of mutual semi-satisfaction and connection. That was interesting to me to explore. Then the breaking of that: You realize the boss doesn't care if I get fired, or I'm going to have a baby, or I have to be away from my baby at three months. There's the moment when all that breaks down, and you realize you're not a daughter to this place.

“I lived in Italy for a year as a junior in college. It left such a deep groove in my psyche. It was another version of family that I experienced. I did live with a host family as Emily does. Emily grows much more attached to her family there, especially the mother figure. I wanted her to have that as one of the references of what a family could look like, or a mother could feel like. She's always searching [for]: What does a mother feel like? What does a family feel like?

“Also, the visuals are so good! It's, again, going back to the stark contrast between the old world versus the new world: Emily going back to Italy and re-experiencing the visual and sensual pleasures of that place after being in Williamsburg for so long (which has garnered this numbing quality by that point). Emily almost returns to her body, too. That's what happens when she goes to Italy for the second time. She lands back in her body in a way. It's when she discovers she's pregnant; it's when she becomes insatiable for food. It's when she has her fight with Megan, and she goes to a dark place. But Emily starts feeling, in this visceral way, [something] she hasn't been for a long time since living in New York and working at this job. She sees the sun behind the two towers in Bologna and feels a presence—maybe it's her mother or the child inside of her. She tastes the grease on the pizza. Italy is about sensual pleasure. I also have these deep feelings about it: deep loneliness, deep sadness, deep beauty. That's where she kind of refuels everything.”

Emily's search for home leads her to all these people and places, and ultimately back to herself as she steps into motherhood. Did writing this book lead you back home, too?

“I definitely think so. A friend (and one of my very trusted readers) read a very early version and said, ‘It's your coming out book; you're coming out as yourself!’ which was so interesting to hear. I don't think I would've put it that way, but it felt like a turn in my writing life for sure. It helped me to, as I said earlier, shape a lot of the experiences that I have gone through and that had felt confusing to me. It helped me to make meaning around them and to connect them to my art practice rather than feel that they were taking away from it.

“That's another thing that was big about this book. Emily wonders if it's possible that motherhood, her personal life, and her life as a woman will someday lead her back to art rather than taking her away from it. I've seen every female artist and writer I know who's become a mother go through this gigantic fear: am I going to lose this when I have a baby? To some extent, you do. I really grieved over what felt like a loss of a part of myself, and part of that was a certain creative self. Then a totally new creative self emerged. I don't know for sure, but I think there's more empathy in that self, and it's more tender. A different writer emerged after I became a mother.”