Before There Were Instagram Models, There Were Video Vixens

For Black women, they represented a beauty that we could own.

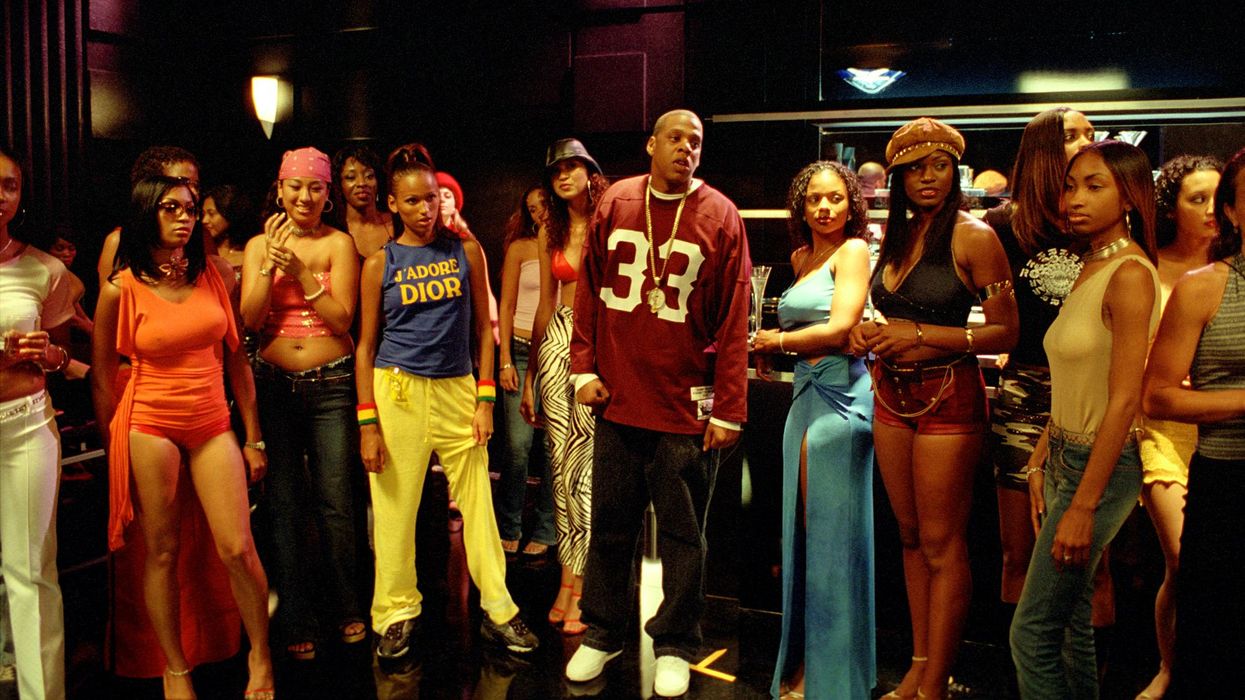

The setup was always the same: a slow-mo zoom to a woman dancing, strutting, or riding in the passenger seat of a very expensive car. They were the most memorable moments of some of hip-hop's most iconic music videos. And for some Black girls, like myself, these shots were formative, laying the foundation for how we would grow to appreciate our own beauty. When video vixens reached peak popularity in the early aughts, we got the rare opportunity to see and celebrate Black and brown women as desirable.

Amidst constant critique about the ultra-sexy, sometimes raunchy legacy of video vixens in hip-hop (mostly coming from Black women themselves), the aesthetic influence of icons like Melyssa Ford, Lanisha Cole, and Buffie the Body is ever-present online. When tracing the origin of the face and body that, in many respects, defines the new ideal physicality on Instagram, it always leads back to the video vixens of yore.

"When you think about how the women on Instagram are now, they kind of look like you can take them and put them in the videos of back in the day," explains King magazine founder and Vibe magazine editor-in-chief Datwon Thomas. "That was the look: the big eyelashes, the long hair, the Coke-bottle shape, and the itty-bitty bikinis."

Attesting to this, last week Jack Harlow and Bryson Tiller dropped a Y2K-style video for "Love Is Dro" while Quavo and Yung Miami recreated Freaknik for the "Strub the Ground" video. For the most part, each of the old school–inspired visuals could have easily been set in 2021. The fixation on these eras' aesthetic benchmarks comes through in the enduring wearability of their fashions and the ongoing aspiration to embody similar physiques.

Though there are distinct common threads, things do look different today. Atlanta-based marketing specialist Kimani Bellamy was inspired to dig deeper into the industry's early video vixens after noticing that Black women weren't featured as heavily in today's rap and R&B visuals. She described watching the video for Big K.R.I.T.'s song "1999" featuring Lloyd and being alarmed that the Black models weren't shown as prominently as the video's white and racially ambiguous leads. Noting that the song sampled Juvenile's "Back That Azz Up" and Guy's "Piece of My Love," she wondered, "'How are you going to make a Black ass song with no Black women [in the video]?"

She's since created The Vixen Memoirs, a podcast and digital library archiving the stories of hip-hop's on-screen heroines. "When I was growing up, I always saw Black women in videos. If it was a Black [artist], there was a Black woman in that video," she says. "I can't imagine people younger than me growing up seeing women in videos who don't look like them. It's like for your favorite artist, you're not even the beauty standard."

In Bellamy's research, the video girl aesthetic was often distinguished with "very glossy lips, a belly ring, and low-rise jeans." Sound familiar? For hairstyling, she said that extensions were popular, but lace wigs weren't as widely accessible as they are now, "so a lot of girls had the natural doobie wrap going on or a perm." Physically, she echoes Thomas's classification, singling out that video vixens always had "big boobs, a flat stomach, and a big butt, but not by our current BBL standards," she clarifies. "They wore natural makeup, a thin brow, lip liner—all of that."

In the prime video girl era, which took place from the late '90s to early 2000s, it felt like there was a concerted effort to champion diversity in music video casting. When I ask Thomas if he senses a similar spirit behind the scenes today, he says, "There's a prioritization, but not necessarily to put [Black women] on a pedestal like how we did."

Growing up in predominantly white spaces left me starving for environments where I could be the ideal because it wasn't what I had grown accustomed to. When I saw these women on 106 & Park's music video countdown, I recall wanting to look like them, move like them, and dress like them. Their brand was aspirational but still felt somewhat attainable.

"When we were growing up," Bellamy recounts, "these women looked like my older cousins. They looked like the girls who live next door to me." She doesn't see the same relatability in the stars of today's videos. Instead, she attributes the morphing visual identity to the cosmetic surgery boom.

"Plastic surgery being more accessible and becoming such a trend means that everyone kind of looks [the same] now," she says. "A lot of girls in current videos aren't recognizable. They all have that 'Instagram baddie' aesthetic."

The concept of the video vixen is still ever-present, but in practice, it's far from what it once was. "I think we entered the post–video girl era when the labels started losing money," says Thomas. "And not just losing money, but when they stopped doing the big-budget videos. Also when social media took off, the girls didn't need videos or magazines to become popular."

Then, in 2005 Karrine Steffans penned a salacious tell-all, much to the chagrin of artists and fellow video girls. Though Bellamy doesn't single-handedly attribute Steffans' memoir to the shift in the industry, she called it the "nail in the coffin." The video girl is symbiotic to the rap video itself. They're still there but with far less fanfare. The video girl hasn't gone anywhere, but the outrage has dulled.

The video's vixen's exclusive emphasis on beauty as opposed to struggle was refreshing and liberating. The outrage is understandable and using beauty as social currency rarely achieves anything but a disastrous outcome, but the fondness for these women also makes sense. They were a break from the norm, from the reality of our everyday life.