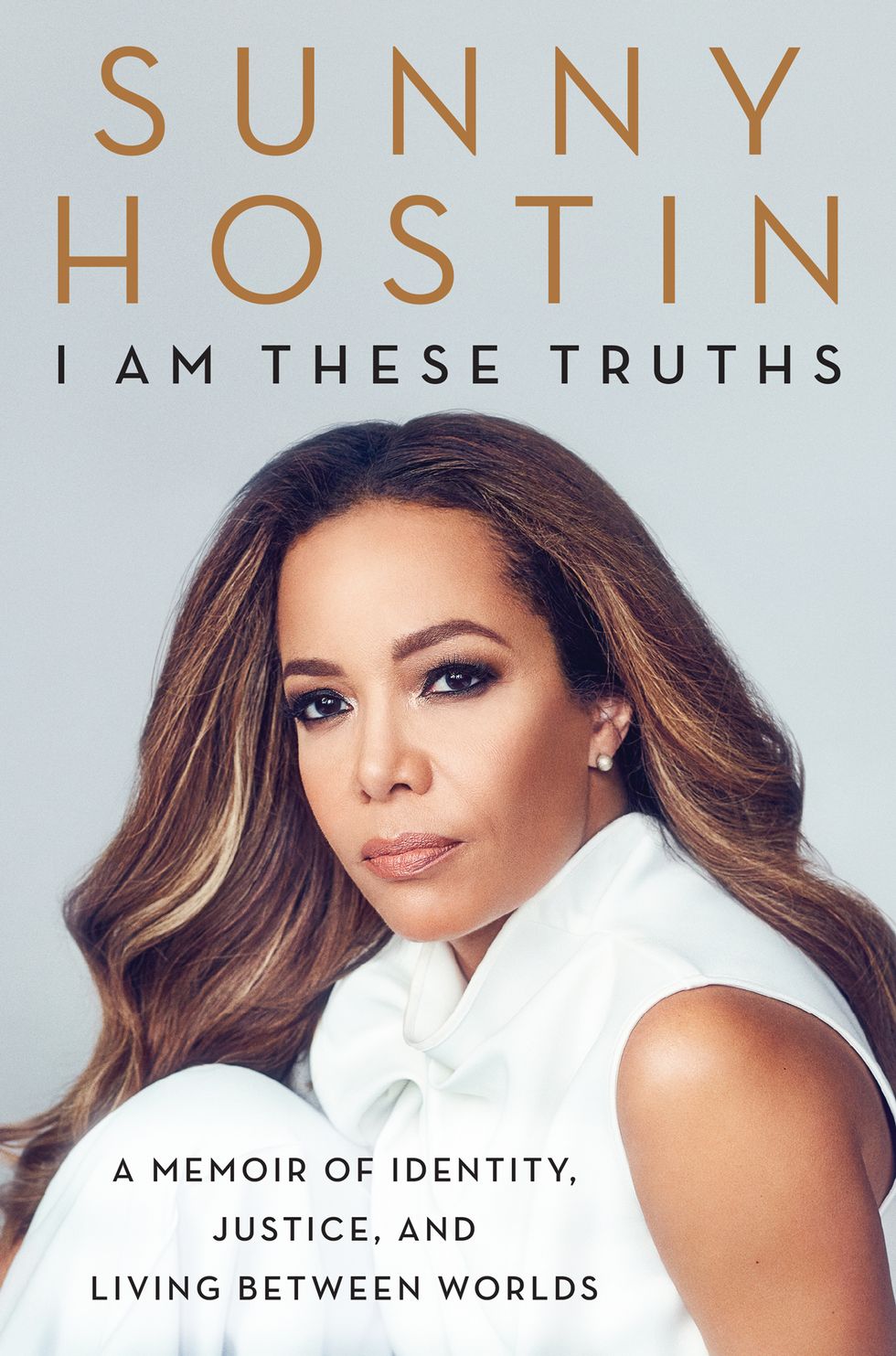

Sunny Hostin on Pioneering Her Own Career and the Complex Issue of Identity

And why she’s cautiously optimistic for the future of media.

Sunny Hostin, co-host of The View and a child of an interracial marriage (which, might we add, was not even legal until 1967), grew up in the South Bronx as sort of a self-dubbed “unicorn.” Hostin struggled with her Afro-Latina heritage at a young age and throughout her career as she came to the harsh realization that it not only caused people to treat her differently, but it led her to second-guess her own performance. However, from that comes great self-reflection and, in Hostin’s case, a memoir.

Her new book, I Am These Truths, which was written in both English and Spanish, recounts the legal journalist’s journey through the media as she battled both racism and sexism. “Once I started writing, I realized that the country was grappling with this role of systemic racism as I was grappling with it, as well,” Hostin tells Coveteur. However, the decision to tell her story wasn’t one she came to easily. She knew she had a great job at a great company and didn’t want to be labeled a complainer or a troublemaker (a thought that plagues so many of us). “I realized if I continued with my position of privilege and power and didn’t say anything, then I was doing not only myself a disservice, I was doing a disservice to women and women of color all over the country that could never be in a position to say something.” We sat down with Hostin, whose résumé is quite extensive, to discuss her career, the complex issue of identity. and the importance of fact-based journalism.

Can you tell me about your background and how you got to where you are today?

“I am a lawyer by training. I started out on the traditional route—I went to Notre Dame Law School, which is kind of a big deal now that we have our supreme court nominee. Then I had my own children. Prosecuting child sex crimes as a mom is a really difficult thing. I actually decided to take a break, but most of my family and friends will tell you that I’m not someone that does well just staying at home. Everybody kind of wanted me to get out of the house because being a mom is kind of the hardest job in the world.

“I ended up finding my way back into journalism—I was a journalism major. The reason I didn’t pursue it initially, and I write about this in the book, my mom was really terrified about me being able to be gainfully employed because, at that time, not only were women underrepresented, women of color, I mean there just weren’t any people that looked like me. She just didn’t understand it. I didn’t pursue it then, even though that’s really what my dream was. I fell back into it. I’m actually really happy that both of my worlds sort of collided in the sense that, as a legal journalist, I get to do good. I get to have both feet planted in the work of social justice through media, if that makes sense. I’m in the perfect place for myself.”

How do you view your role as a legal journalist that’s trying to do good? Are you trying to highlight stories that aren’t talked about?

“There aren’t many legal journalists. So, for me, I get to kind of forge my role especially as a woman of color. My space is in the social justice and in the criminal justice space because that’s what is important to me. What I try to do is really educate our viewers about criminal justice, about social justice and how there are so many voices that aren’t heard. I try to voice that perspective in the framework of hard facts because I think that is what is missing in the conversation—it’s such a personal and emotionally fraught conversation, so the underpinnings of the facts get kind of squishy. So when you’re talking about something like Breonna Taylor, what is a no-knock warrant? Was it a no-knock warrant? What did the ballistics report look like? And what is a ballistics report? I’m able to kind of outline that or explain it in a way that is digestible, I think, to the everyday person, not only through my experience as a prosecutor, because you’re really just a storyteller when you’re speaking to a jury, but also as a journalist. It’s a very comfortable place for me to be.”

Do you ever struggle to remain objective when you’re covering something ridiculous?

“I don’t struggle with the facts, but I do get kind of infuriated when I’m accused of being too close to a story, of skewing the facts or letting my opinion change things. My analysis is based on fact. It’s interesting to me because being a lawyer is applying the facts to the law. Being a legal journalist is the same thing, so that’s not troublesome to me. You’re really just fact-checking most of the time and telling a story. What does sadden me is that people twist the facts to arrive at their own conclusion, especially when race is involved—when you have a police shooting of an unarmed man or woman, usually a Black man or a Black woman, and the story becomes ‘Let’s demonize the victim.’ That, for me, has been very hard to witness. I see all these pieces in the media and it’s always ‘Let’s tell the story about Breonna Taylor’s boyfriend,’ and it’s usually wrong and it’s usually not fact-based and done by people who don’t have expertise in the law. That kind of thing has been very difficult to see.”

What are some of the fundamental issues that you address in the book?

“I address the issue of identity, social justice, and how people tend to try to define everyone, try to put you in a box. James Baldwin even said, in terms of identity, when we let others identify ourselves, then we’re in trouble. We have to be allowed to identify ourselves. When people tell you their experiences, you must listen to them. We have to examine them in order to write the wrongs. No one is immune from it, even me. Also, what was striking to me is that I write about Trayvon Martin and how it really changed my life. It was sort of that ‘aha’ moment that Oprah talked about. That happened in like, 2006, and here we all are. It’s unbelievable. So many people found their voice when that happened. I think there will be a lot of people that find their voice from George Floyd. For me to be writing this and realize that we are still in this movement and that that moment shaped not only me, but shaped a generation, I knew that it was the right time to put the book out.”

Photo: Miller Mobley

Photo: Miller Mobley“It’s been defining—I will say that. My parents were an interracial couple who got married in 1968. The Loving Decision (the supreme court decision allowing their marriage) came down in 1967. So it’s no surprise that I was sort of a unicorn growing up. I was defined by the fact that I was the product of the first generation of a legal interracial marriage. It sounds crazy, doesn’t it? That’s why I say it out loud. I was raised being told ‘You’re the best of both worlds.’ I got a lot of that pep talk from my parents.

“You don’t want to write about this. I didn’t want to play the race card. You never want to be accused of that. At work, I was thinking, ‘Am I really being treated differently? I don’t know. Am I working hard enough? Am I being excellent?’ Like my father would always say, ‘Just be excellent, nobody can take that away from you.’ I feel that I am being excellent, but I’m hearing that I’m not getting paid as much and I’m not getting the same opportunities. Why is that? I was sort of smacked in the face with the fact that, wow, it really was because of my race. That is not only really disheartening, it requires great self-reflection. It’s certainly something that has colored, for lack of a better term, my experience in life and certainly in my career.”

Do you think it makes you a better journalist?

“I absolutely think it makes me a much better journalist—a much better lawyer because I have a unique perspective.”

I know you often speak about “little indignities.” Can you talk about how significant they can be?

“I’m always so reluctant to point them out because they do seem so insignificant in the larger scheme of things. We’re in a global pandemic. People are dying. There are people that have lost their livelihoods. Then you’re thinking, ‘I’ve got a good job. So what if I’m making less than the person sitting next to me?’ That’s an indignity. Then you start to think, ‘I’m on the number one talk show in the country. I have this incredible platform where I can reach people. I’m a possibility model for so many little girls and boys of color, BUT I wasn’t given a dressing room on the same floor with the main hosts,’ and while no one else knows that, I know it. Would a white woman with my experience be on the third floor? That’s an indignity. Should I just shut up and dribble? It’s that kind of thing that you don’t want to complain about because you know you’re so much better off than a lot of other people, but you should be treated equitably. I realized if I continued with my position of privilege and power and didn’t say anything, then I was doing not only myself a disservice, I was doing a disservice to women and women of color all over the country that could never be in a position to say something.”

What was it like personally to publish something that was so candid?

“It was really scary. I knew that I’d run the risk of again being labeled a troublemaker, almost traitorous. I wasn’t sure if it was sort of a career killer, but I still thought it was the right thing to do. I went so far as to ask my husband, ‘Is this something that I should do? Will this make me unemployable?’ We’ve got two kids. One is college bound, and the other one’s going to high school. Thankfully, I have such a great support system, the response was like, ‘Hell yeah!’ You have to because you don’t want to have to live with yourself later. What’s wonderful is the response that I’ve gotten. It wasn’t ‘What a troublemaker.’ It was ‘Thank you for speaking up and speaking out,’ and even from my company, ‘We need to recalibrate.’ Maybe that’s a result of the reckoning that’s going on in the country, or maybe it’s a result of antiquated thinking. Maybe I just thought people wouldn’t listen.”

Are you optimistic for where the media industry is heading?

“I’m cautiously optimistic. I don’t think that we will see real systemic and sustainable change until there are more decision makers that reflect true diversity. Not just in front of the camera, but also making editorial decisions. I feel that companies are getting better at the diversity piece, they’re getting better at the inclusion piece, but that equity piece seems to still be really difficult for them. When I say equity, I mean equity in pay and I also mean equity in opportunity. Why are the white guys still all anchoring the evening news? Why are they getting paid more money? Why are people so opaque when it comes to what folks are getting paid? I think the equity piece has a long way to go, and until we see real change there, I will remain cautiously optimistic.”

Photos: Miller Mobley

Want more stories like this?

Meet the Director Changing the Narrative of Black Women in America

Meet the Creative Director Reminding Us What True Authenticity Looks Like

The Duo Behind Fashion Tech Connects Shares Their Strategy for Tackling the Issue of Inclusion in the Industry