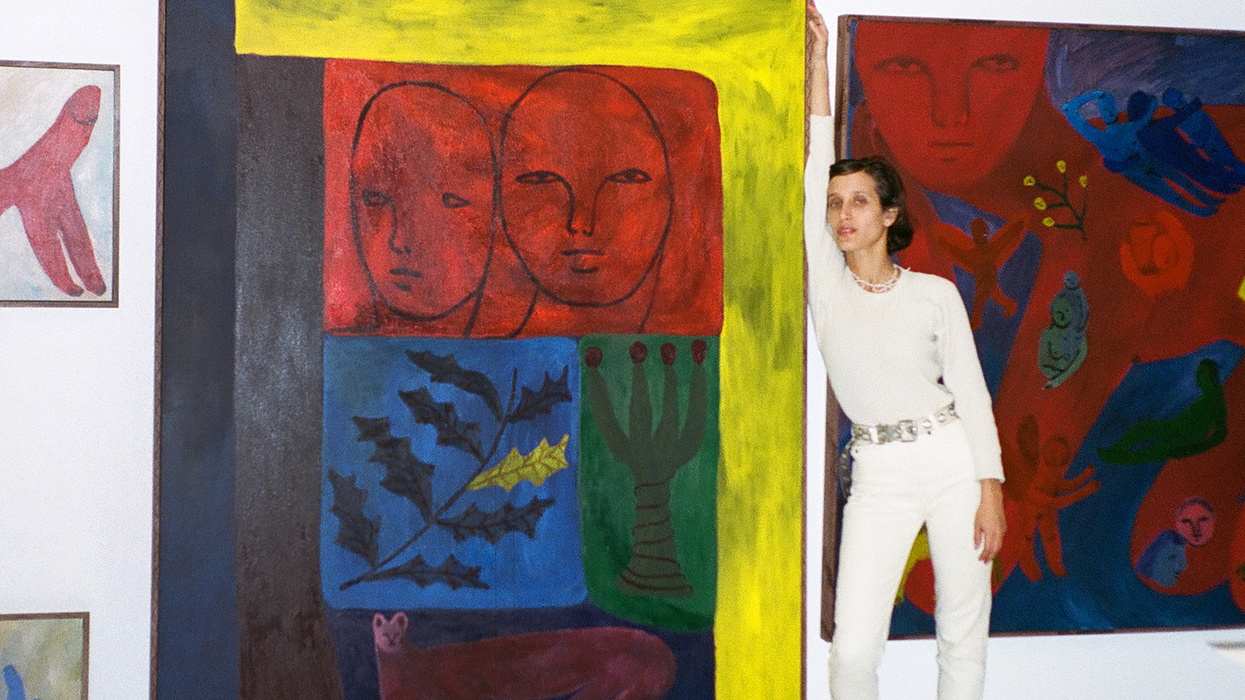

Emma Kohlmann’s Dance Between Humans and the Natural World

Ahead of the release of her inaugural book, Emma Kohlmann: Watercolors, the artist talks about embracing color, finding solitude, and what it means to be an artist.

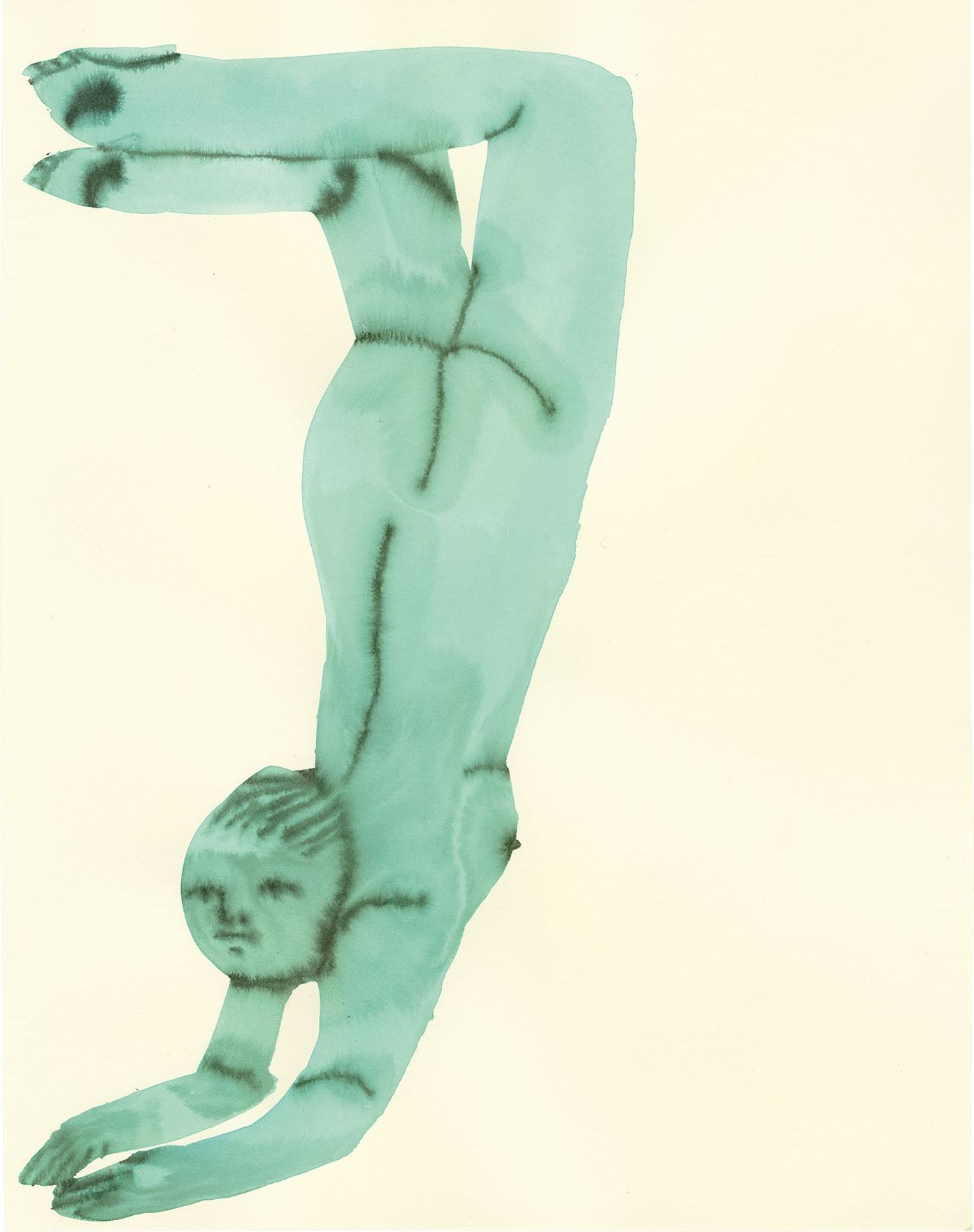

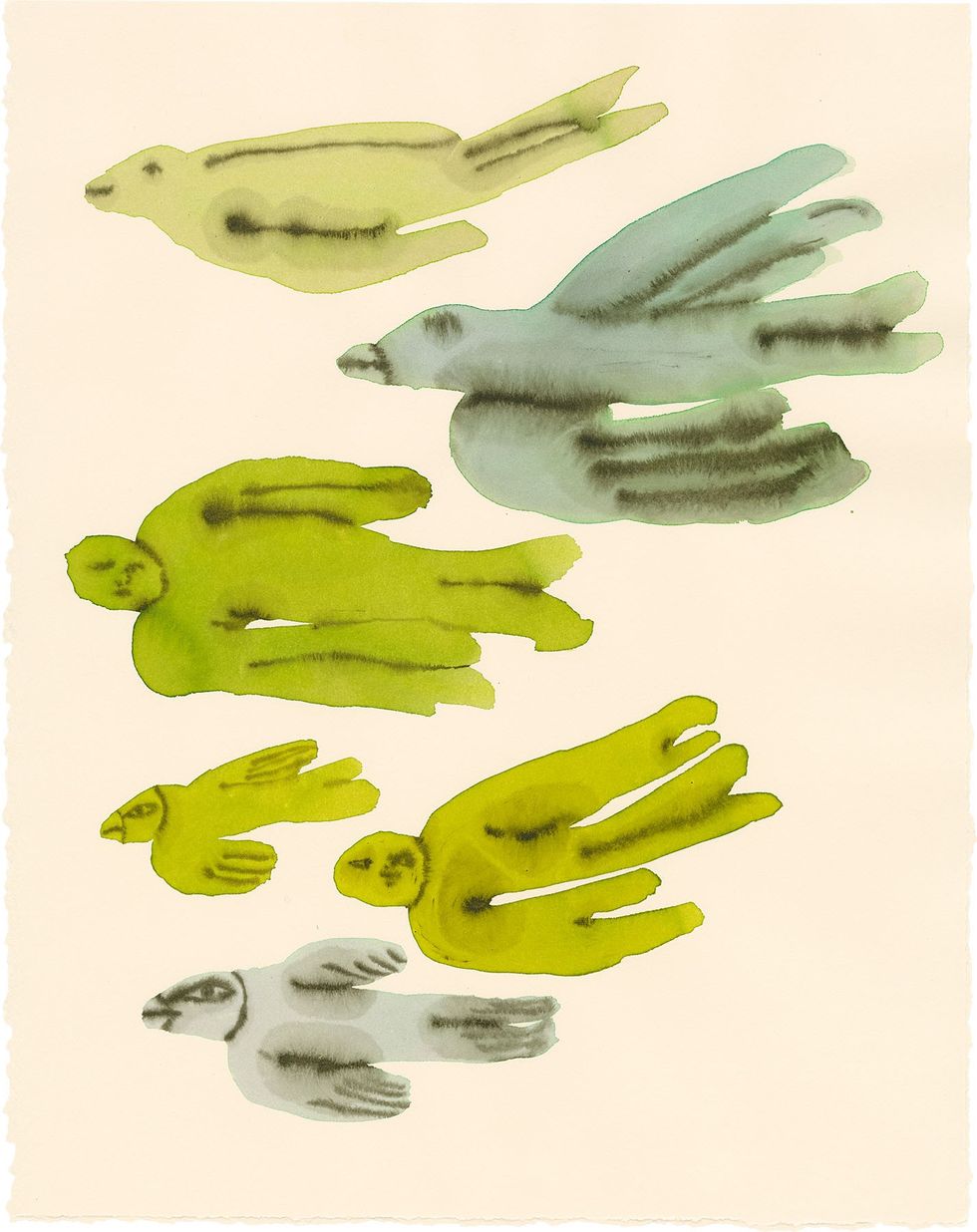

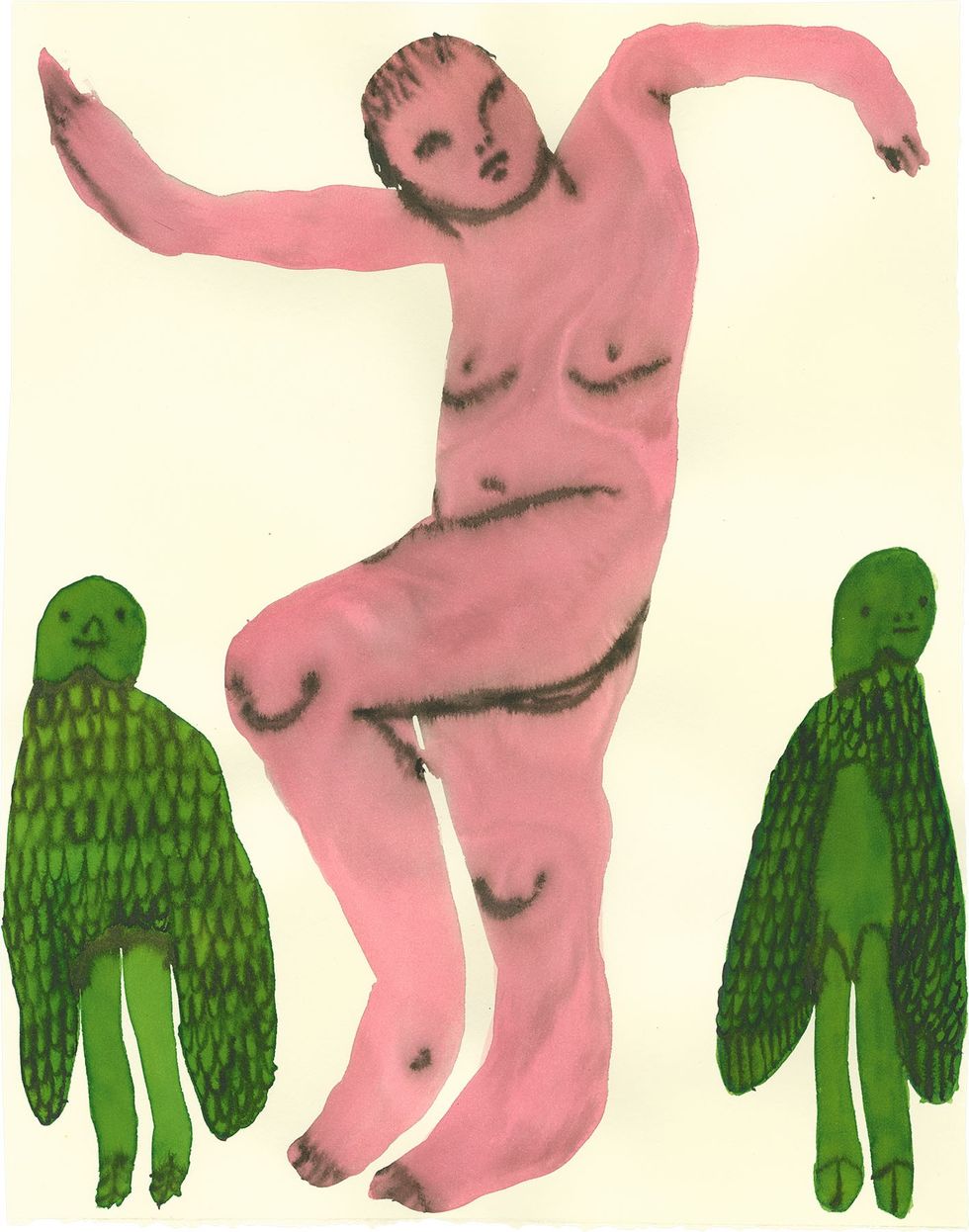

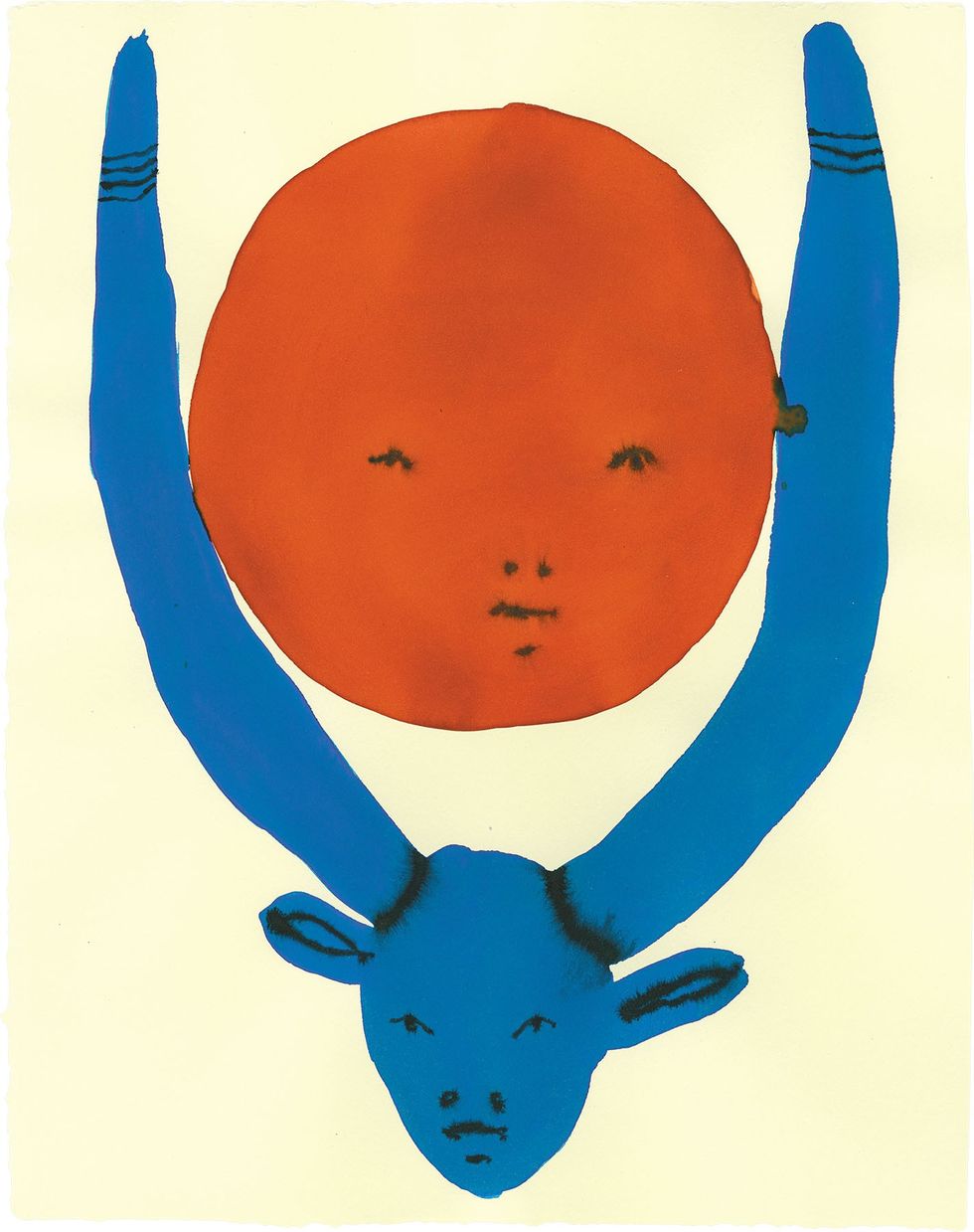

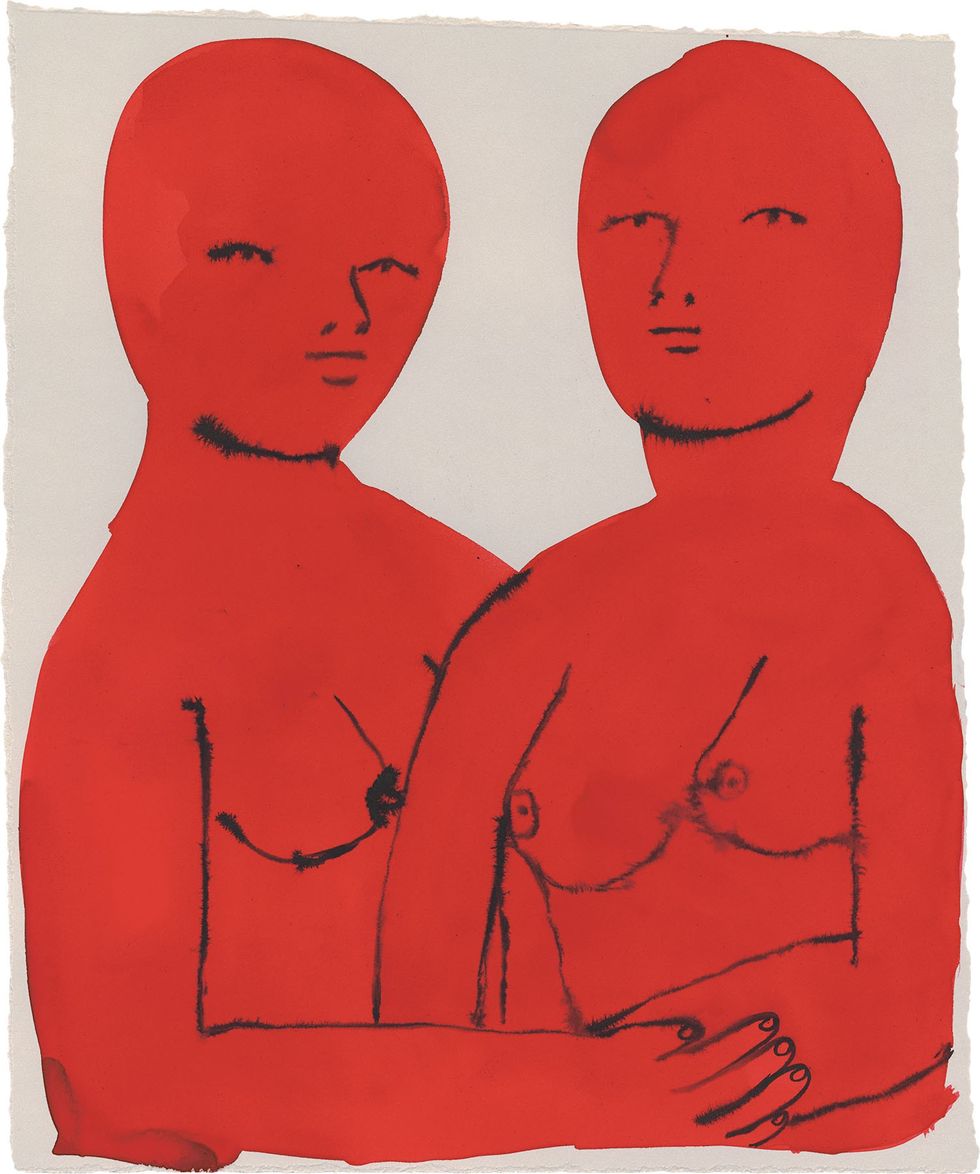

Emma Kohlmann’s watercolors capture the “dance between humans and the natural world” with her distinctive economy of line and color. The artist’s figures, unanchored by traditional signifiers of gender or identity, connect with viewers on the universal wavelength of human emotion. Whether her figures are playful, peaceful, or mischievous, Kohlmann uses monochromatic swathes of color to animate her vibrant narratives. Her inaugural book, Emma Kohlmann: Watercolors, tracks her progression from 2011 through 2021, from the greyscale tones of her early work through various chapters of experimentation and her ultimate mastery of color.

Ahead of the release, published by Anthology Editions, we asked Kohlmann to shed light on the curating process, her roots in zine-making, and the artistic ruts and breakthroughs that led her to where she is now.

Courtesy of Emma Kohlmann

Courtesy of Emma Kohlmann

How would you describe the process of assembling your first book? What emotions did it bring up seeing a decade of your work canonized in print?

Emma Kohlmann: Art-making can feel abstract at times. I have an innate need to paint, but where the physical work lands often feels unknown. This series of watercolors started in my senior thesis in 2011. I was an undergraduate at Hampshire College, and it became a practice of mine to make ten, twenty, or fifty watercolors a day. At the time, I was only working with sumi ink, which makes a gray-washy tone. This routine in my practice has served me many years after college. I have accrued over a thousand works on paper since then, and it feels like it has a home in this book. It felt scary to go through these works, trying to select ones that suited the overall feeling of the book. It took some time to figure out the organization and flow. Only a third of the watercolors are in the book. To be honest, it was intense looking back, just because the work felt so old or irrelevant to me. I feel differently about it now because I like the feeling of holding pieces individually as if they are their own story.

You stated before that it took a while to feel comfortable calling yourself an artist. Why does that term feel so loaded, even for people who make a living from their art?

EK: At the time, I think I believed that the term “artist” was used too liberally. When a person calls themself an artist, there is an implication that you might not have a job. There are aspects of having a schedule around a studio that can be very privileged. There is definitely a class component of living in your imagination that feels unimportant or unserious. Like, is that a real job? I have definitely been asked that. What exactly does that mean to be an artist? Is it bound by a capitalist monetary exchange, or is it what you make or create? It can be both. I think I will always struggle with it.

How did your background in punk music and zine-making influence your artistic practice? How did it inform your personal style, both artistically and otherwise?

EK: I feel the most free in my mind when I am creative. Zine-making and working within alternative art spaces have afforded me this freedom to think outside the normal trajectory of an artist. Self-publishing gave me a regimented schedule when I really had nothing else going on. I wrote and illustrated zines as a way to communicate with other artists that I admired. Dedicating each zine to a specific theme, allowing flexibility of materials, length, and layout—I developed my own ideas through this process. Another aspect of zine-making is that it gave me a community of people to work with and reach out to for feedback. I didn't really feel comfortable in most spaces that were for artists because I technically didn't study art in my higher education. It has always just been something I did, and this part of life really uplifted and supported me. I have immense gratitude for that.

Courtesy of Emma Kohlmann

I read in an interview that, within your work, you aim to create a world where “everything is on the same spectrum; there’s no hierarchy.” How do you express this utopian balance visually?

EK: I think there is a dance between humans and the natural world. I see that dance within my own work. I have my own visual language that works within this. Each plant, animal, and shape feels alive within this world.

Although your works are figurative, they are unanchored from traditional markers of gender or identity. As the artist, do you ascribe certain personality traits or attitudes to these figures? Are the figures all unique abstractions, or are there recurring characters that exist within the same creative universe?

EK: I don't really see the figures in my work as characters. I see them as one long narrative. I think of them as emotions or mood pieces. They hold weight despite not vocalizing. I rely heavily on color to motivate this feeling.

When you’re in a creative rut, where do you return for inspiration?

EK: When I am having a hard time in the studio, I go to the library. I look at my favorite books. I have a large collection of art books and zines. I just recently reorganized my personal library to reflect this. It really has helped me hone in on what I like about collecting books. I like making up my own categories to organize them by, like books that are tools for the studio, powerful artist monographs, poetry, and self-taught artists. Before I collected books, I spent almost every day at the art library near my house. I learned a ton just by perusing the stacks. When I feel like there is no inspiration, I will just dive into a new topic of study, like archaeology or furniture design. I try to remind myself what I like about making my own work through the lens of research.

Courtesy of Emma Kohlmann

Courtesy of Emma Kohlmann

In general, how much does your environment–LA, NY, Massachusetts, etc.—influence your work?

EK: For many years, I traveled from place to place with my watercolors. I would save up money and go away for the winter. I was lucky to have cheap rent and a job to come back to in Western Massachusetts. I really didn't know where to land for the longest time. I felt like being in a city was important, but I didn't feel like I had the means to go back. I really loved how the medium lends itself to traveling. I could be anywhere. I find solitude wherever I am. It's not really about the place but my own ability to focus. I love working in Western Massachusetts because I can really be alone. I am an introvert/extrovert. The ability to have balance is really important to how I work. I am excited by new places and the possibilities they can inspire in my practice.

You work with a very distinctive color palette. Do you associate any significance with certain repeated colors (blue, red, yellow, and green)? How has your relationship with color changed over the years?

EK: Color has played a major role in how I developed my watercolor practice. I started making work only with sumi ink because I feared color. I didn't really know how to trust my instincts when it came to color. Going from sumi ink, which is saturated in deep blacks and grays, to blue rather than red was a trajectory I never thought I would follow through on. I associate color with specific time periods. Crimson red was such a major turning point in my series. I was developing a narrative around the sexuality of these figures. I thought of them as fiery and in love. There was sadness to the color as well. Sumi ink black and gray was used for abstracting the body. Slate blue became the color to elongate and play with the figures like a landscape. Each time I experimented with a color, it became a new way of working on something new until I started to combine the colors all together.

What is the last work of art that made you swoon?

EK: Two shows I recently saw that really stuck with me were Barbara Wesołowska at Silke Lindner and Cathleen Clarke at Margot Samel. Both are very different painters, and I think their work really inspired me to paint!

Courtesy of Emma Kohlmann

Rapid Fire Questions

What’s your guilty pleasure? Hot baths

Hidden talent? Ice skating

Irrational fear? Falling downstairs

Desert-island album? On the Beach by Neil Young

Something you used to hate but you love now? Driving

The best mistake you’ve made? Not moving to a city

Who is your dream collaborator? Louise Bourgeois

Best piece of advice you’ve ever received? “Keep it simple, stupid.”