Dapper Dan: The Master Conductor of Black Culture’s Sweet Style Symphony

We caught up with the iconic haberdasher at his Harlem atelier to chat about his childhood, spirituality, and mentorship in the fashion world.

21 January, 2021

Fashion

Makeda Sandford

10 November, 2021

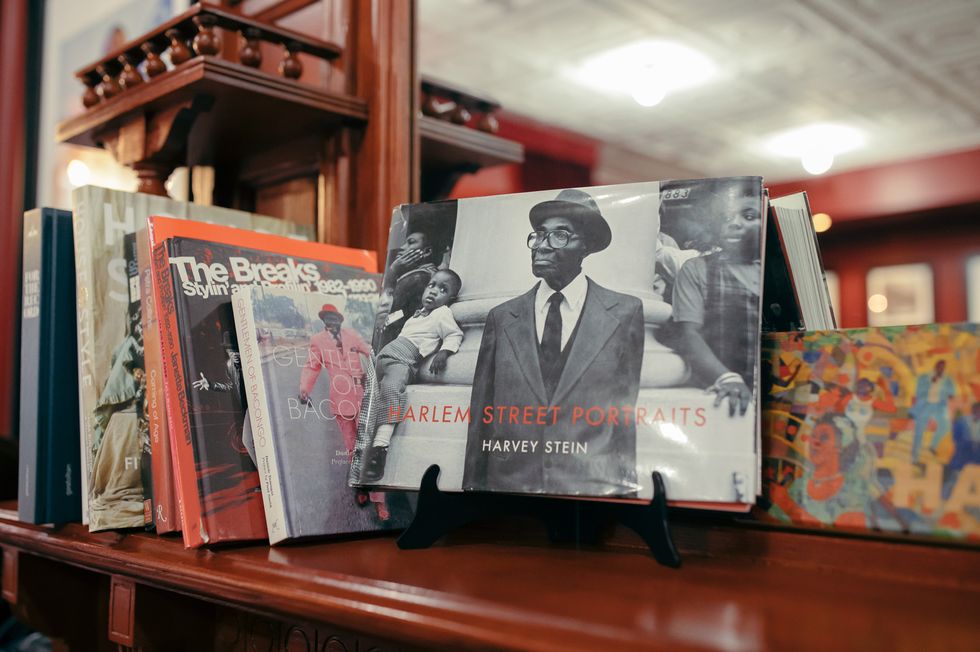

“I’m ready to be interrogated,” Dapper Dan laughed as he sat on his couch in a vivid red vest and button-down white shirt from the last photo shoot of the day at the Malcolm X Boulevard location. Though we were running over, I was more than willing to block off the rest of my day if it meant sitting down with one of the iconic visionaries responsible for the bridge between hip-hop, fashion, and Black culture. As I walked around to find a comfortable seat, I was greatly overwhelmed with the feeling of luxury, exclusivity, and Black excellence, from the velvet decor to the warm-toned indoor lighting to complement the setting sun at 4:00 PM on a Tuesday.

I finally found myself seated in a chair directly across from him, but with safe enough space between us to respect social-distancing boundaries in the middle of a pandemic. As I propped open my laptop, I looked up to notice photos of some of his most notable work with TLC. To be able to sit in a room with the ex-Harlem hustler turned creative connoisseur who spoke foreign, challenging languages of fashion and was translated onto the bodies of Jay-Z, Tracee Ellis Ross, Regina Hall, and 21 Savage was nothing short of a blessing.

To my right was his son Jelani, who had been on set all afternoon working as a photographer, and to the far left, past the fireplace and flat screen, was his mentee, 18-year-old Tay. As Dapper Dan rested comfortably, I was still wrapping my head around the idea that this was happening. What was initially slated to be an hour-long interview transformed into a two-hour candid conversation far beyond any journalist’s expectations.

With that, we chatted with the couturier—born Daniel Day—in the upstairs of his Harlem-based atelier for two hours to discuss the influence of his childhood upbringing on his love for fashion, his discovery of spirituality through his 1974 trip to Africa, and how he and his children are developing new relationships with one another as we transition into the new decade.

I finally found myself seated in a chair directly across from him, but with safe enough space between us to respect social-distancing boundaries in the middle of a pandemic. As I propped open my laptop, I looked up to notice photos of some of his most notable work with TLC. To be able to sit in a room with the ex-Harlem hustler turned creative connoisseur who spoke foreign, challenging languages of fashion and was translated onto the bodies of Jay-Z, Tracee Ellis Ross, Regina Hall, and 21 Savage was nothing short of a blessing.

To my right was his son Jelani, who had been on set all afternoon working as a photographer, and to the far left, past the fireplace and flat screen, was his mentee, 18-year-old Tay. As Dapper Dan rested comfortably, I was still wrapping my head around the idea that this was happening. What was initially slated to be an hour-long interview transformed into a two-hour candid conversation far beyond any journalist’s expectations.

With that, we chatted with the couturier—born Daniel Day—in the upstairs of his Harlem-based atelier for two hours to discuss the influence of his childhood upbringing on his love for fashion, his discovery of spirituality through his 1974 trip to Africa, and how he and his children are developing new relationships with one another as we transition into the new decade.

“I was given that. I have three older brothers and two older cousins, and we all lived in the same building. They all liked me, so I learned so much at an early age. The only male in my family was my father, and he was the only one that worked a regular job while everybody else was hustling. I learned everything about hustling from my uncles and cousins, and by the time I was thirteen, I learned everything about the streets. There was an older guy named Dapper Dan, and when he came home he would hang out with me, and he was amazed at how good of a hustler I had become. One day he said, ‘I’m not Dapper Dan anymore; you’re Dapper Dan. From now on, my name is Tenor Man Dan.’

“He was amazing—jet Black, pearly white teeth, pimp style, a barber, a con man, and a major gambler. You know how you go to college and get degrees? In Harlem we get degrees in different ways of hustling, and he knew it all. When he saw a young guy like me coming from his neighborhood who could do it, he gave me the name Dapper Dan and called himself Tenor Man Dan because he played the saxophone. I didn’t realize there were so many older guys that I learned from who couldn’t read. I had no idea.”

When did you know that fashion and style was for you?

“As a means to make money, or as a means to transform my life? Because fashion transformed my life literally—clothes, which involves fashion, transformed my life. I grew up very poor. Goodwill was our Macy’s, and all I got was hand-me-downs until I was old enough to get clothes for myself through street things as young inner-city kids. The projects were not the bottom realm—the tenements were. The tenements are where nobody really wanted to live, and that’s where we had to live. It was very important to me and my self-esteem to feel like I was somebody, to feel good about myself, and that’s what fashion did for me. So much so that I refused to go to school if I wasn't fly. I used to ask my brother to borrow his clothes before I went to school, and if he didn’t let me borrow his clothes, I would sneak them out of the house. He used to catch me, so what he did was sit by the door when it was time for me to go to school. You know what I did? I told my friend to stand by the back window and I would drop his clothes out the window, and he’d see what I’m wearing when I go downstairs, but I’d change in the hallway. That’s how critical it was.

“It was my only gateway to feeling like somebody, you know? I can’t remember the last time I saw a person ashamed of what they had on. Maybe it’s not that big of a thing, but it was the only way to make you feel and look like you were transitioning. That’s a big reason why people who come out of the ghetto of Harlem get Cadillacs and Mercedes even before they get homes; they need that instant gratification that everybody can see. They can park, drive through, and walk in the hood, and that’s more visible than having a home in Long Island. The mentality was instant gratification and to transform yourself. What sparked my desire for clothes is how it transformed my life and the way people see me. I get dressed and go downtown, but nobody knows where I live.”

“The first impression of people that you see are the older guys on the corner. Later, I learned that a lot of them couldn’t even read, but it was about the respect that they got. Humphrey Bogart, George Raft, Edward T. Robinson—all of those guys in the ’40s and ’50s who played those gangster roles were my first influences because they had an impact on the subculture in Harlem, because it was instant money. Instant gratification requires instant money to satisfy those means. Everybody in Harlem was not the Harlem you see today; this is the third transition for Harlem. Harlem back in the day was an African village. We all migrated from the South, and [within] all of these different sections of Harlem, you found people from the same town. We had these pockets that generated a certain type of cohesiveness amongst us [as] a Black people coming from the South and struggling.

“What had a lot to do with the transitioning of Harlem from a village to a ghetto was the end of Jim Crow. Jim Crow had a lot to do with Harlem being the mecca for Black culture. In Harlem you had all different classes of Black people, and that was only because of Jim Crow. As soon as it began to evaporate, Harlem began to change because the uppity Black people could leave and the red lining was relaxing. It had a lot to do with the culture of Harlem, and the culture in Harlem has always been defined by what distinguishes how you dress. You couldn’t even come on 125th Street when I was growing up if you weren’t dressed; you’d be embarrassing yourself. That’s how serious it was. People got dressed up and everything. That defined my relationship with fashion, and that was the first door that I could open that made me feel like I’ve been elevated.”

Tell me about the relationship between hip-hop and fashion—how have you played a role in bridging the two important pillars in Black culture, and how have you seen the relationship strengthen?

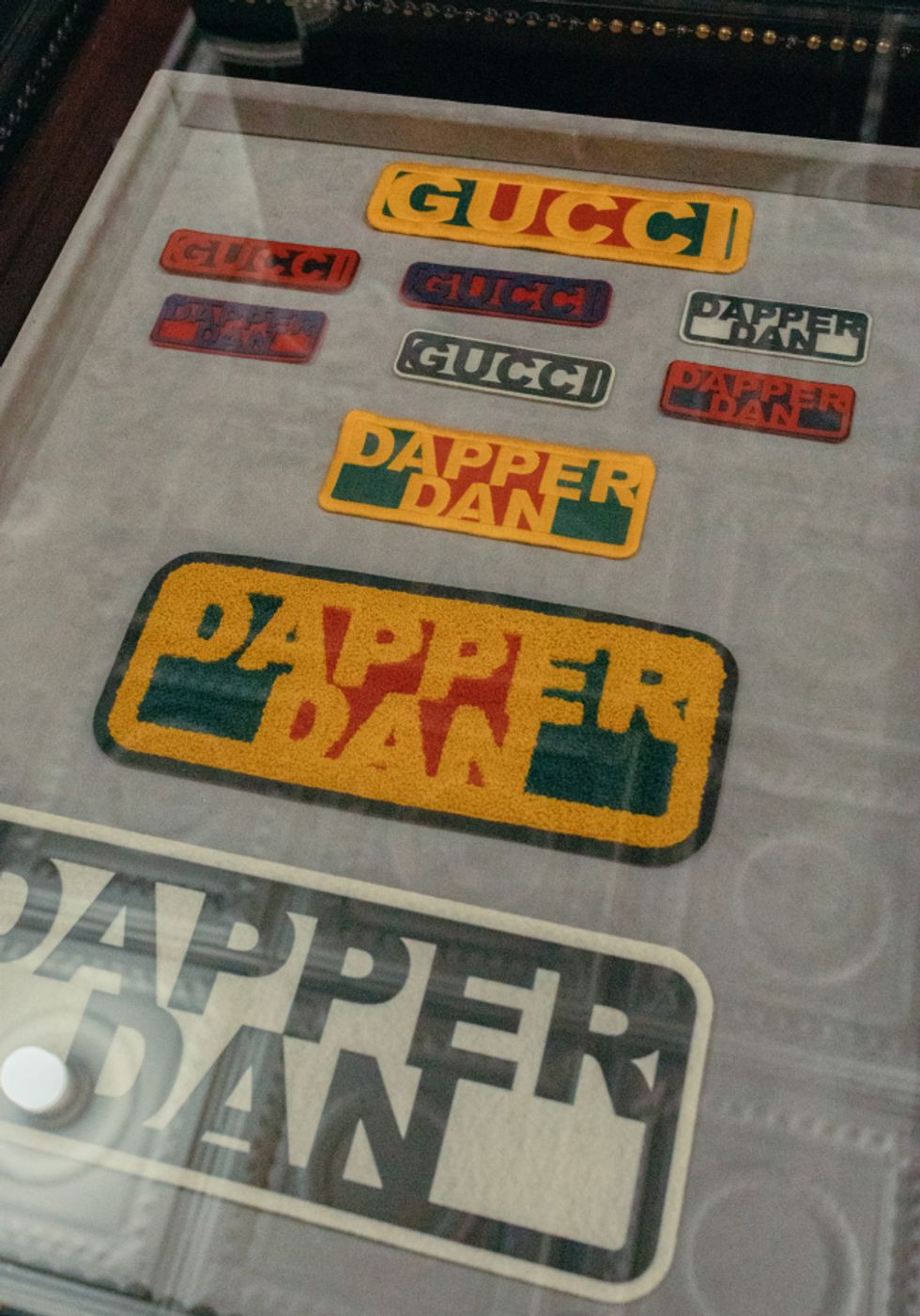

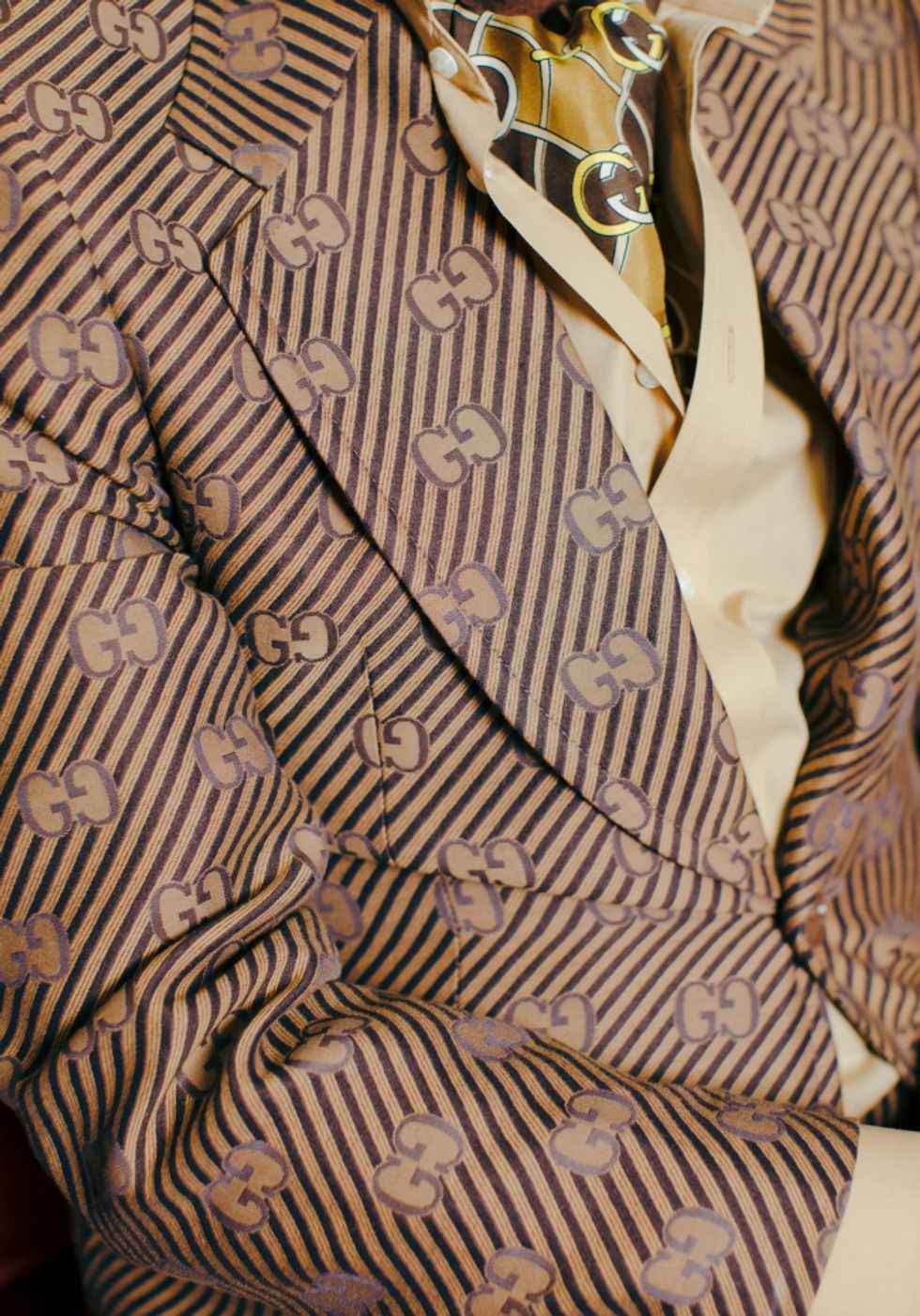

“When hip-hop started and I had just opened my store, the cultural trait of hip-hop was taking its pointers from the streets. Basically from hustler culture, but not like Los Angeles hustler culture. The rappers initially wanted to be like the hustler. They wanted the jewelry and the swag. In the beginning I just translated that in a way that would fit them. What they needed was something that basically defined them. In the process of the translation, I took luxury logos and fashion in a way that gave them the swag in a unique way to define them. It was a departure from when I was doing minks. The rappers were eventually able to afford the minks, but initially they were with the expensive sweat suits, leather jackets, and things like that.”

“I took luxury logos and fashion in a way that gave them the swag in a unique way to define them.”

“I don’t like the word designer because it’s too restrictive to how I’ve always [seen] myself. I always saw myself as more of a conductor for an orchestra. You know how designers do collections? To me, I assemble different parts of an orchestra and bring them together. The parts of the orchestra are like parts of the community and different elements of the community. I took the Rasta look, I took the Nation of Islam look, I took all of those elements and brought them together as opposed to what designers do. Designers make collections that are a reflection of themselves; I never did that. I always made things that were collections of the community. That’s why I think that I had longevity—because I always reflected on what the people liked, and I put that together in a way that they felt connected to it.”

You’re obviously a creative who’s one of one. How would you describe your style and your aesthetic?

“Can we approach this question by me stating what makes me me? I was born and raised in east Harlem, the juncture where Blacks, Puerto Ricans, and Italians were all mixed together. The house that I grew up in was a stone’s throw from the Harlem River. As a child, we swam in the Harlem River in our underwear, and to swim in the Harlem River, you had to know something about rivers because it was dangerous. No lifeguards, none of that. Before we swam in it, we used to go down to the bank of the river, because we didn’t have toys, and scoop up clay to make figurines. Before we swam in the river, we used to take a popsicle and throw it in the river to see which way the current was going. Wherever you wanted to get out at, you would jump in the river based on the direction of the current so you won’t have to swim against it.

“As I began to change my life, I began to see the imprint that it had on my mind, and I kept thinking about that river. Rivers have fashioned my life. When I describe myself, I describe myself in rivers. Growing up, I was forced to use the Harlem River to enjoy myself. If Harlem was an African village, the Harlem River was like a river running through an African village. When I describe my life from what it was, it subjected me to a type of lifestyle that really wasn’t me. It was a lifestyle that was generated by the oppressiveness passed down from slavery. My father was born 33 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, and my father’s father was born a slave. My mother and father were part of the first migration to come from the South. I had to find out why what happened to me happened to me.

“When I went back to school, I was part of an educational program, and we had these scholars, Dr. Ben Jochonnan [and] Dr. Henrik Clarke, [come] into the Urban League Education Program to teach us. Because I was writing for 40 Acres and a Mule, I ended up having to make a choice about accepting a scholarship from prep school, [going] to Columbia, and [ending] with an internship over the summer, but I chose to go to Africa and visit seven countries because I needed to know. The same way my path led me to find out why Black people suffered the way they did, I had another pathway to find out the real essence between man and God, heaven and hell. When I stumbled across Man’s Higher Consciousness and the metaphysical world, I started reading all the books by Professor Hilton Hotema and esoteric teachings. I went from ‘Don’t worry, God’s gonna bless you when you get to heaven’ to ‘Don’t wait till you die to get your pie in the sky.’ I’m going through these challenges of Black consciousness.”

“The most pivotal moment that further launched my career on the pathway that took me to where I am today was when I couldn’t buy wholesale luxury goods to sell. They kept denying me, and when I finally found somebody who would sell to me, I was buying from them, but the guy who I was competing with in Harlem was also buying from them. He had a big, popular store called AJ Lester’s. I ended up having some jackets that they were carrying and they were selling them for $1,200, and I would sell them for $800. They went down and told the guy that I was buying from, ‘If you sell to Dapper Dan, I won’t buy from you anymore.’ You know the brand Andrew Marc? That’s when they first started out. I met them because I used to buy from their uncle, because I initially went into the fur business. When he told me that his nephew was starting a business, that’s how I ended up meeting them.

“When I went down to Andrew Marc, they said, ‘Listen, we got a problem. I can’t sell to you anymore because AJ Lester won’t buy from us if we sell to you. They have five stores and you only have one, but we don’t want to see that happen to you, so what I’ll do is sell you the same jackets, but I gotta take the tags out.’ But I’m an arrogant Black man and I ain’t got anything else, so I just [walked] out. I had been in Africa and when I was in Africa, I had all my clothes made. When I went over to Africa, I went super fly and they liked my clothes. When I went to the market to buy clothes, they liked everything I had on and said, ‘Wanna trade?’ I traded a whole wardrobe that I went to Africa with for artifacts and had them make me clothes. That never left my mind. What I did is I had Africans make me clothes, and I made those same jackets. From that point on, I began to make clothes.”

Take me back to 1982 and the launch of the Dapper Dan store. How’d you get from opening day to the beautiful atelier and empire you’ve created?

“Middle-class and upper-class Black people would not buy from me. The ones who were buying from me were those who could care less about what the status quo thought about it, what’s fashionable and what ain’t fashionable. Those were my first clients: the gangsters. They launched my career. They liked what I was doing, and what I did was look at luxury fashion because I always loved luxury stuff. I looked at it in a way that nobody looked at it before.

“I was studying symbols, and James ‘Jack’ Jackson came into my store, and he was like the Al Capone of Harlem. He was one of my main clients, and he came into my store with a Louis Vuitton pouch with $100 bills. A light went off in my head and I said, ‘Damn, if that’s how they feel about that pouch with those symbols on it, imagine if I could have them walking around looking like that pouch.’ That’s how I launched, and I was determined to teach myself everything I could about textile printing, sewing machines and everything. I began to do the same thing that I did to understand African-American and African history—I read books.”

“When everybody started getting high and using drugs, I asked myself, why did I do that, and why did I get high? Fifteen months I was getting high off heroin, and then I got caught. I didn’t even go away for 90 days, but when I came home I read Malcolm X’s Message to the Grassroots, where he says, ‘If you understand the flower, study the seed.’ I wanted to find out where it came from and why it infected me. I studied it and wrote an article on how Black people got addicted to drugs in the Schomberg [Center for Research in Black Culture] in the newspaper section. From that point on, I knew that everything I wanted to know, I could teach myself. Everything that’s happening here today is what I taught myself. I realize that when I look at something, I only look at it through Black eyes. I can’t see it through any other color eyes, and I learned how to translate that. I’m not trying to be white, I didn’t grow up in a white world, I’m not trying to go to Paris as a white man or a Black designer. I’m going to Paris as a Black man.

“I’m gonna excel as a Black man, and I’m staying right here where I was born and raised. I’m the first generation of the Great Migration and the last generation to be born in Harlem before a major drug epidemic because it didn’t hit me until the ’60s. All of that registered with me and built within me to fortify me, make me wanna know things, gave me the feeling to be independent, self-sustaining, and vertical. One of the most fortunate things about my life is that I saw Black people do it by themselves—hustlers in the street, hobos by the river in the shantytowns, and people living on their own means. I saw people rise and fall, and they can never make it worse than I’ve seen it. No matter how many times they push me down, I’ll always get back up. Some of the things that shaped me are when people tell me what I can’t do. That gets me. I can’t do it? Nah, you’ve got the wrong guy.”

Walk me through your creative process. Has it changed over the years?

“This is a real critical juncture in fashion and fashion culture of the streets. Remember, I initially created luxury couture. I ‘Blackenized’ luxury culture and couture. When I got underground, [new designers] ‘ghettorized’ it. I took luxury fashion and made it suitable for us, in a way that looks like us and reflects us. I kept it upstairs, expensive and luxurious. When I got run underground, that’s when all those other brands came out and ghettorized it; it was cheaper, anybody could have it, and all the brands became cookie-cutter. Everybody was walking around with FUBU looking the same. As a result of them ghettorizing it, all of the brands collapsed. When those brands collapsed, the European brands began to copy what I initially did and took it back upstairs. They made it more refined, more luxurious, more expensive. What they did was go back to my blueprint.”

“Those were my first clients: the gangsters. They launched my career. They liked what I was doing, and what I did was look at luxury fashion because I always loved luxury stuff.”

“When I started out, who would ever think that I would teach myself what I taught myself? Who would ever think that Jay-Z would be able to do what he did and teach himself? I’m looking for kids that I could create within now. I want to see the next Jay-Z, I want to see the next Dapper Dan. I want to help kids who don’t have a lot because that is what lends itself to what we need in our culture. We need more vertical mobility, and that is a big thing when it comes to other kids seeing another kid come from the bottom. That’s why I stay in Harlem, I’ll never leave here, take the bus, take the train so people can see me and identify with me.”

Where do you see the future of fashion, style, and creativity, especially for Black creatives?

“Now we’re coming up on something that’s really important to me. You know why? You can answer that question for me, and let me tell you why. How do you see my place in fashion, and how do Black people see my place in fashion? A lot of Black people don’t understand me. The only people who understand me are the ones who read my book. They think I’m creating clothes and my objective is to fashion clothes. No, my objective is to fashion minds. This is just a ploy that I initiated to reach people, especially young people. I ain’t into this thing like that—fashion. I’m into opening minds and fashioning minds.”

With the spark of all the racial controversy and cultural appropriation amidst the Black Lives Matter movement, how do you believe mainstream high-end brands have done a poor job at mindfulness when it comes to Black and brown communities?

“This is a big thing that’s going on. The major problem with the conflict between the Black Lives Matter movement and the major brands is that the major brands didn’t involve us monetarily in the creation of designer brands. Therefore, they made a lot of cultural mistakes. I think that created the biggest problem between the culture and [luxury] brands. Even when they realized they had a problem, they didn’t move fast enough to do something about it and didn’t put us in the key positions that would have resolved it early. Instead, they wanted to just appropriate money to different organizations. That’s a Band-Aid. No, you’ve got to put us right there where the creative process takes place so that things like that wouldn’t happen. I think now they’re catching onto that—at least Gucci is.”

Want more stories like this?

This Emerging Brand Is Shaking Up the Fashion System with Collections That Are Personal

Zerina Akers Is Helping Black-Owned Businesses Take Centerstage for Years to Come

How Mara Hoffman Used the Pandemic as Her Fashion Wake-Up Call