Career

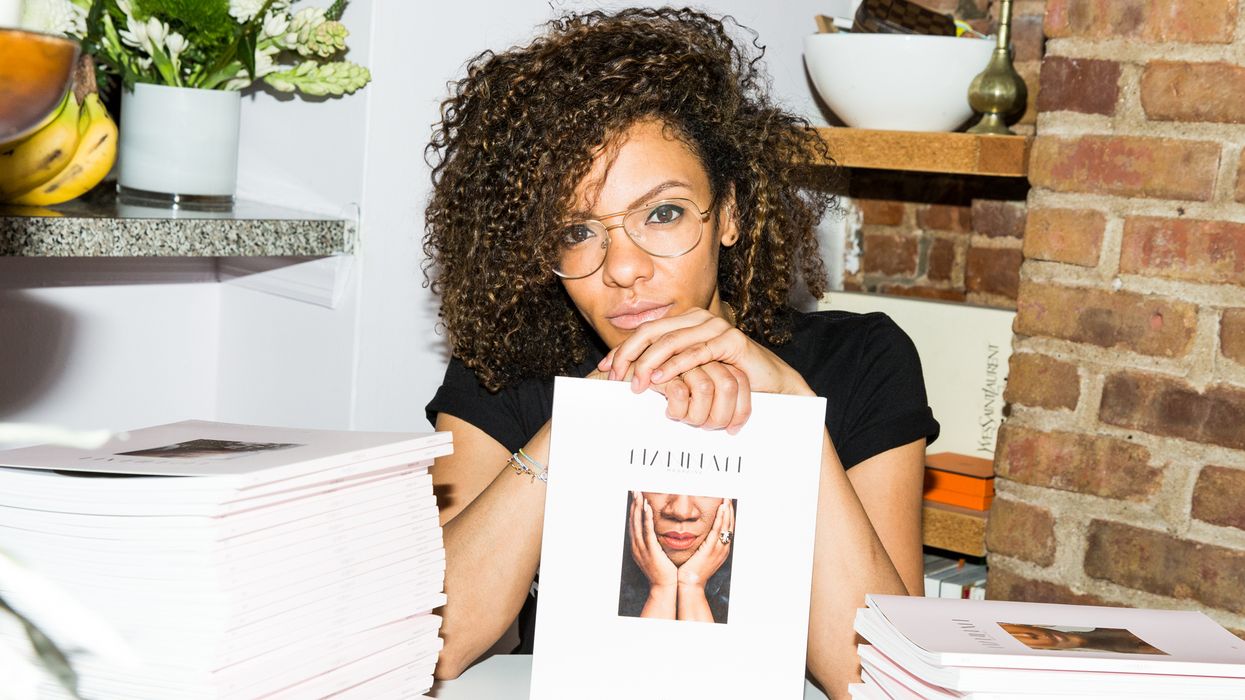

Qimmah Saafir was Tired of Black Women Being Overlooked by Magazines, so She Launched Her Own

At home with the founder of HANNAH.

16 July, 2019

Alec Kugler

10 November, 2021

We arrived at Qimmah Saafir’s Brooklyn apartment fully intent on discussing HANNAH, the biannual print publication she founded, in her words, as “an ode to black women.” We wanted to know what inspired the magazine, how she got Issa Rae and Tarana Burke on covers without the glossy allure of a Hearst or Condé Nast umbrella, and the vision she has for HANNAH in the years to come. We accomplished this, but unexpectedly, there was someone else in the room we were just as interested in getting to know: Saafir’s two-year-old daughter, Leahn. So, as we discussed the challenges of launching a print venture in the age of digital fixation, we also snacked on Goldfish and snapped some mother-daughter portraits.

One of nine siblings born and raised in the Bronx, Saafir grew up in a tight-knit family more mindful of what they did have then what they didn’t. “We had a house, and it was a great house, but we were poor,” she says. “My siblings and I never really noticed, though, because my parents did a really great job of surrounding us with so much love and activity that we never felt like we were without. We had each other, so we had enough.”

After graduating from Bronx Science High School, Saafir went to Spelman, where she majored in English and minored in Japanese. Though she planned to pursue international business—even living in Nagoya for a year—a discovery her freshman year hinted that she was perhaps destined for something else.

“I saw the first issue of Honey with Lauryn Hill on the cover, and I was like, ‘This is a magazine for me. Specifically for me.’” A magazine made in celebration of and dedicated to young black women was a marvel at the time, and like many of her peers, Saafir collected every issue and was crushed when Honey folded in 2003. “[Around that time] it started brewing to create something similar, but I just didn’t know how.”

Saafir’s first job out of college was in event planning at Columbia University, working in the office of president Lee Bollinger. It didn’t take long for her to realize it wasn’t a fit, and soon after she delved into publishing, writing for The Ave., a since-shuttered social and political magazine. Later she landed at XXL as the sole research editor—a job much bigger than the paycheck she was earning, she says.

After graduating from Bronx Science High School, Saafir went to Spelman, where she majored in English and minored in Japanese. Though she planned to pursue international business—even living in Nagoya for a year—a discovery her freshman year hinted that she was perhaps destined for something else.

“I saw the first issue of Honey with Lauryn Hill on the cover, and I was like, ‘This is a magazine for me. Specifically for me.’” A magazine made in celebration of and dedicated to young black women was a marvel at the time, and like many of her peers, Saafir collected every issue and was crushed when Honey folded in 2003. “[Around that time] it started brewing to create something similar, but I just didn’t know how.”

Saafir’s first job out of college was in event planning at Columbia University, working in the office of president Lee Bollinger. It didn’t take long for her to realize it wasn’t a fit, and soon after she delved into publishing, writing for The Ave., a since-shuttered social and political magazine. Later she landed at XXL as the sole research editor—a job much bigger than the paycheck she was earning, she says.

“After XXL I decided to freelance, and that’s when I started to work at every single magazine there is. Seventeen, InStyle, Lucky, Marie Claire, Maxim…everywhere. I was doing writing and research, but I would always get discouraged with the writing because I would pitch stories on women of color, and the response would always be ‘That’s not our direction’ or ‘That’s not our demo.’ This was before #blackgirlmagic—before we were a trend—and I got tired of trying to force stories on women of color into the pages of other magazines.” A mentor gave her some simple, straightforward advice: “You’ve had this idea for your own magazine for years,” they told her. “Just do it.”

Without financial backing to get the project off the ground, Saafir reluctantly started a Kickstarter (“I didn’t want people to think, ‘Oh, here she goes begging for money.’”) She ended up surpassing her goal, and thus, HANNAH was born, named after what her late father and his grandmother called the sun.

Saafir describes the process of putting the magazine together as “loosely formulaic,” likening each issue to a time capsule. When deciding whom to approach for covers, she asks herself, “What black woman has done something in this time frame that’s historic? I want to make sure that when we look back on these books we can say, ‘Yeah, that was a big moment.’”

Members of the HANNAH team include deputy editor Aja Riddick, whom Saafir has known since high school; designer William Pope, Leahn’s father, who also goes by Pope Phoenix; creative producer Robert Vance; special events coordinator L’Rai Mensah; and assistant Kennedy Williams, among numerous others. They work with different writers, photographers, and stylists on every issue.

Without financial backing to get the project off the ground, Saafir reluctantly started a Kickstarter (“I didn’t want people to think, ‘Oh, here she goes begging for money.’”) She ended up surpassing her goal, and thus, HANNAH was born, named after what her late father and his grandmother called the sun.

Saafir describes the process of putting the magazine together as “loosely formulaic,” likening each issue to a time capsule. When deciding whom to approach for covers, she asks herself, “What black woman has done something in this time frame that’s historic? I want to make sure that when we look back on these books we can say, ‘Yeah, that was a big moment.’”

Members of the HANNAH team include deputy editor Aja Riddick, whom Saafir has known since high school; designer William Pope, Leahn’s father, who also goes by Pope Phoenix; creative producer Robert Vance; special events coordinator L’Rai Mensah; and assistant Kennedy Williams, among numerous others. They work with different writers, photographers, and stylists on every issue.

“When I first started HANNAH, people thought I was crazy,” Saafir says, citing the steep declines in print circulation, “but shortly after the first issue came out, there were all these articles [being published] about how mainstream magazines are folding, but very niche, independent publications are thriving.”

So what does Saafir consider to be the draw of HANNAH in particular?

“The draw is that it’s something that was not. There was a void, and the draw is something created well—and intentionally, with love—specifically for black women. This is just in celebration of us, unapologetically.”

Thus far, pages have been dedicated to the work and words of Toyin Ojih Odutola, a conversation between Jenna Wortham and Morgan Rhodes, interviews with Ruth Carter and Joy Bryant, and many more nods to black women. And while HANNAH is for everybody and anybody who wishes to read, learn from, and appreciate it, there’s one person in particular Saafir hopes it resonates with.

So what does Saafir consider to be the draw of HANNAH in particular?

“The draw is that it’s something that was not. There was a void, and the draw is something created well—and intentionally, with love—specifically for black women. This is just in celebration of us, unapologetically.”

Thus far, pages have been dedicated to the work and words of Toyin Ojih Odutola, a conversation between Jenna Wortham and Morgan Rhodes, interviews with Ruth Carter and Joy Bryant, and many more nods to black women. And while HANNAH is for everybody and anybody who wishes to read, learn from, and appreciate it, there’s one person in particular Saafir hopes it resonates with.

“Leahn was born when the first issue of HANNAH was born,” Saafir says, looking at her daughter. “I want her to see me working and creating something that I love, but I also want her to see herself. When she looks at HANNAH and she sees faces that look like her, that matters to me.”

Saafir’s long-term goal is to grow the publication into a multimedia platform that focuses on various underrepresented groups, though celebrating black women will always be at its core. Her plans to scale are ambitious, but according to her, she’s already experienced unparalleled success.

“Before we put the first issue out, we did a content preview on Tumblr of what the layouts would look like, and a lot of people started following it,” she says. “I got a letter from a girl who I want to say was in Missouri or Nebraska. It was handwritten, and she said, ‘I want to let you know that what you’re doing with HANNAH, it makes me feel like I’m home anywhere I go. I’m in college where I’m the only black person, but when I go to my room, I go online and look at HANNAH, and I feel like I’m safe. I feel like I’m seen.’

“If we never get any more press, if only two people buy the next issue, that one letter will be enough. That’s why I do this.”

Want more stories like this?

4 Years After Cofounding Black Lives Matter, Patrisse Cullors Is Still Fighting “Like Hell”

Meet the Venture Capitalist Backing Your Favorite Brands

Everything You Need to Do to Build Your Personal Brand

Saafir’s long-term goal is to grow the publication into a multimedia platform that focuses on various underrepresented groups, though celebrating black women will always be at its core. Her plans to scale are ambitious, but according to her, she’s already experienced unparalleled success.

“Before we put the first issue out, we did a content preview on Tumblr of what the layouts would look like, and a lot of people started following it,” she says. “I got a letter from a girl who I want to say was in Missouri or Nebraska. It was handwritten, and she said, ‘I want to let you know that what you’re doing with HANNAH, it makes me feel like I’m home anywhere I go. I’m in college where I’m the only black person, but when I go to my room, I go online and look at HANNAH, and I feel like I’m safe. I feel like I’m seen.’

“If we never get any more press, if only two people buy the next issue, that one letter will be enough. That’s why I do this.”

Want more stories like this?

4 Years After Cofounding Black Lives Matter, Patrisse Cullors Is Still Fighting “Like Hell”

Meet the Venture Capitalist Backing Your Favorite Brands

Everything You Need to Do to Build Your Personal Brand