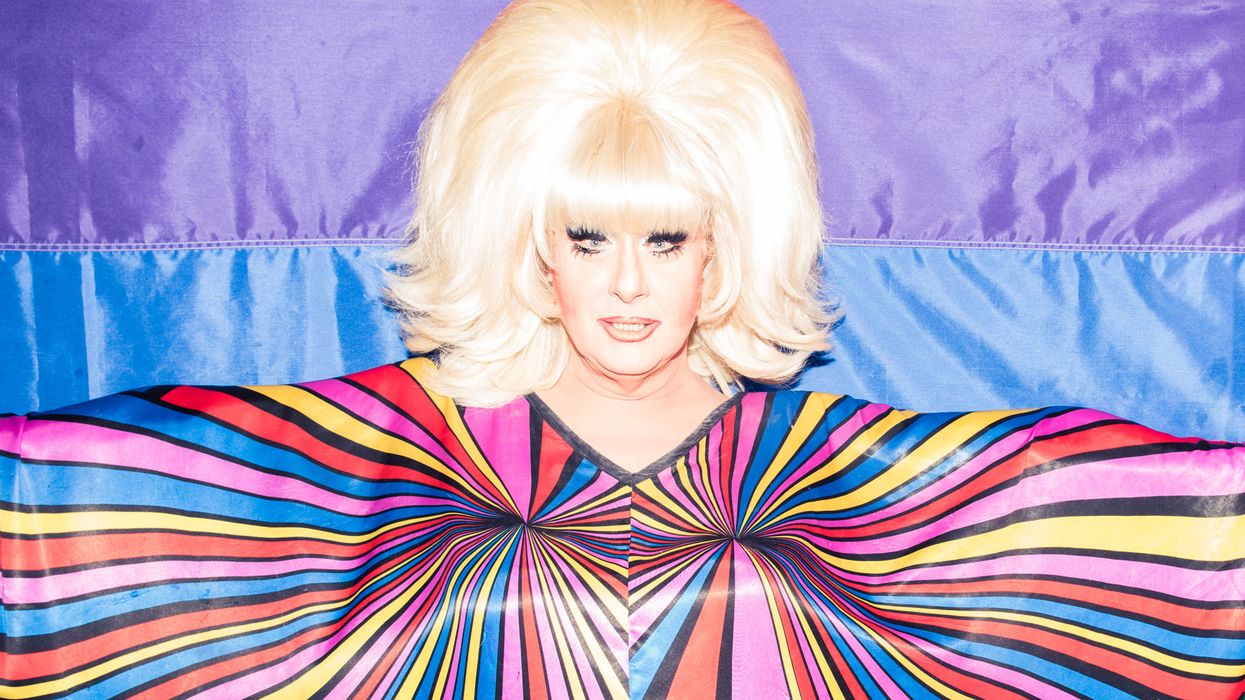

New York’s Most Legendary Drag Queen

Lady Bunny goes on the record on the gay community’s current state of affairs.

When a woman has especially big hair, we've often heard it described as being full of secrets. Well Lady Bunny's hair is about as big as it comes, but we don't think it's full of secrets. In fact, we're not sure she has any secrets at all.

In case you’re not familiar, Lady Bunny, or simply Bunny, is a legendary drag queen. She got her start with RuPaul in Atlanta, and since then she’s been on Sex and the City, RuPaul’s Drag Race, and in this editor’s favorite movies, To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything Julie Newmar, and Party Girl. She’s currently performing a run of her comedy show Trans-Jester, which is every Monday through Wednesday, at 7PM, through June 29 at the legendary Stonewall Inn.

When we set up our interview with Bunny, it was about a week before the attack on Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando. And while we had initially planned to chat her up on her sense of style, (truly) fierce tongue, and what it’s like to be a drag superstar, our plans changed. Walking in to Stonewall, which is being designated a landmark by President Obama this year, we walked past a massive vigil to the 49 victims of the massacre. In this place, which is credited as the birthplace of the gay rights movement following riots in 1969, we spoke with Lady Bunny about her thoughts on the issues facing the gay community in 2016, and what it means to have a safe space, like Pulse was, violated.

About her show:

“Trans-Jester is raunchy, politically incorrect comedy—anything from Adele to Bruno Mars parodies, to riffs on pop culture. It’s full of surprises [laughs] and there’s even a few original tunes and show tunes, which I’ve never done! In there somewhere there is a message that, as a comedian, I’m scared about the word police stifling discussion, and when I hear that mainstream comedians like Jerry Seinfeld and Chris Rock no longer play at colleges because the kids are so politically correct… Going to college is about broadening your horizons, not staying where you’re comfortable. I think that we’re stifling conversation, rather than having frank discussions.

“We’ve become so precious, and it almost seems like people are looking for things to be offended by. I think part of it is that we’re online a lot, we’re not in each other’s faces. We’re online, and email or text communications do not convey tone. You might meet me and find that I’m a very nice person, and then maybe I might get your pronoun wrong, and you’re not going to melt down because we’ve just had a connection. It takes different people time to learn.”

Her reaction to the Orlando attack:

“I was horrified. I certainly don’t want to put my personal connection above anyone who lost their life or loved one there, but I did work at that club several times even before it was called Pulse, I worked there when it was called Southern Nights twenty years ago! I know the owner, it’s very unfortunate, and I work in clubs and I would like to think that I would be safe, and not gunned down on the dance floor.

“But, this is such an involved issue. There’s gun control, there’s mental illness, there’s his possible connection to ISIS...Was he homophobic, or was he actually gay and was this internalized homophobia? It’s so much to process.

“Obviously when you’re coming out of a tragedy, we grieve, and then we try to think about how we can stop this from happening again. And while I’m sad about it, these massacres are becoming a way of American life. This is going on in our churches in South Carolina, schools at Sandy Hook, movie theaters, military bases, and now a gay club. You almost—and this is awful to even contemplate, much less even say—but you become numb because you’re so used to it, and you’re so used to politicians not doing anything. I’m not a religious person—and I know that prayer is a way that people process grief, but there were a lot of prayers after Sandy Hook. They didn’t work. We need to hold our elected officials accountable and if we don’t want weapons that are invented for a battlefield on the streets, we need to get some laws passed.”

The importance of having a safe space:

“You know, sometimes I hear straight people saying ‘why do they need a gay pride day, we don’t have a straight pride day?’ It’s because you were never forced to be in the closet, and you didn’t have to wrestle with negative messages from your church, schoolmates, family. This was a Latino night at Pulse, and in some Latin families there’s a macho culture that makes it harder to come out, and so, yes, you would need a place to go and act gay, because you couldn’t do it at home.

“Not all parents are supportive, so imagine you’re coming to grips with who you are, whether it’s gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender—you might well have old fashioned or religious parents who don’t accept you. You don’t feel like playing baseball, you feel like Vogue-ing [laughs]! So to have a gay club where you can go and be yourself—and this is very important for my generation because, far from getting married, we weren’t accepted even to the extent that we are now—the gay club was the only place where a large group of gay people met, to queen out to that Diana Ross, Whitney Houston, or Madonna song. To dance in a provocative way, or to wear obviously flamboyant club attire, or next to nothing! This was where we bonded, this was where we had our lingo.

“But it’s in these areas where we live where we feel safe. In New York, sometimes I forget that—as someone who grew up in Tennessee—[in parts of the country,] sometimes that car is going to go by and you’re going to hear ‘fuck you fa**ot,’ or you’re going to hear that bottle go whizzing by your head that someone threw at you, if it doesn’t hit you in the head. My response to that was to get away from it, because I could, and I moved here.

“What if you’re a kid from the projects, and you can’t be yourself at home or you could be killed? You can’t Vogue in the park. The Christopher Street piers is where they had a safe space, and as the West Village has become increasingly gentrified, they’ve been driven out to an extent. The Highline is beautiful, it’s clean, but some of us miss it when it was our space—and sometimes there was sex goin’ on there, or there was hustlin’ goin’ on there, sometimes there were knife fights, or Vogueing battles—I’m not saying it was all rainbows, and goodwill towards the community. But it was home.

“And with the Castro in San Francisco out-pricing some of its older gay residents, well, they no longer sit on the boards that make the decisions for these outrageous festivals. So if you’re raising children in that neighborhood, maybe you don’t want them to see topless lesbians, or leather men with pierced nipples, or...whatever! It’s not a gay safe space if it’s being shared with people who frown on our community.

“I don’t know where people’s safe spaces are going, but I do find it very, very telling that people are still coming here to Stonewall. There were thousands of people in the street on Sunday for an unannounced vigil, there were thousands more the next night when the mayor spoke.”

The importance of the Stonewall Inn:

“One reason why I wanted to do this show at Stonewall was that it’s the birthplace of gay rights—it’s about to be landmarked by Obama. My arthritis is getting so bad they could just bronze me and stick me out in the square [laughs]—but this is the birthplace where they had riots against the cops [in 1969]. It was the night Judy Garland died, who was beloved in the gay community as an icon, and I think that aggravated things, but also the cops were coming to bust the joint up. [One night], people stood up, and they threw bricks [and rioted.]

Since then, [the West Village] is where gay people lived, where they congregated, and you still see that today. It is four days after the massacre, and they are still coming to pay their respects—which makes me cry a little bit, because sometimes the gay community is at eachother’s throats, and it takes a tragedy like this to bring us together. I’m glad we still have the capacity to come together.”

The biggest challenges the gay community is facing:

“If I were to leave the comfort of Manhattan and walk around in four wigs and a rainbow caftan, I could easily be the target of violence in different communities. I don’t think people really feel safe, still. Once you leave that big-city bubble, even if you’re just going to Long Island, being gay still rubs some people the wrong way.

“And so while we have rights like marriage, or the ability to be in the military, there are people who do not like that. And every advance we get, it ticks them off. We’re not seeing people’s attitudes change, we’re seeing laws change.

“There are religious leaders that have said they’re glad this guy shot up the club, religion has always been used to bash the gay community. When Kim Davis, the marriage clerk, said, ‘Even though gay marriage is legal, my religion tells me I can’t do that.’ If you think about the consequences of this religious freedom argument, they are so far-reaching, and they go way beyond the gay community.

“[But still right now] the Human Rights Campaign [is fighting a law in North Carolina] that says that while you can get married in the United States, and you can come out in the United States, you can also be fired from your job, or [denied housing because you’re gay.] I did a benefit in North Carolina [fighting that law,] and some people at the event were told that if video of them at this benefit, fighting for their own rights got onto social media, their job would be gone. So no, we are not free, and we do not have equal rights.”